Japan approves human-animal embryo experiments

Pixabay

- The experiments will involve inserting human stem cells into rat and mouse embryos.

- Some bioethicists are concerned about the potential harm this could inflict upon animals.

- Organ shortages are a problem all over the world. In the U.S., as many as 20 people die every day while waiting for a transplant.

The Japanese government plans to let a stem cell researcher conduct human-animal embryo experiments, with the ultimate goal of someday creating organs to be transplanted into humans.

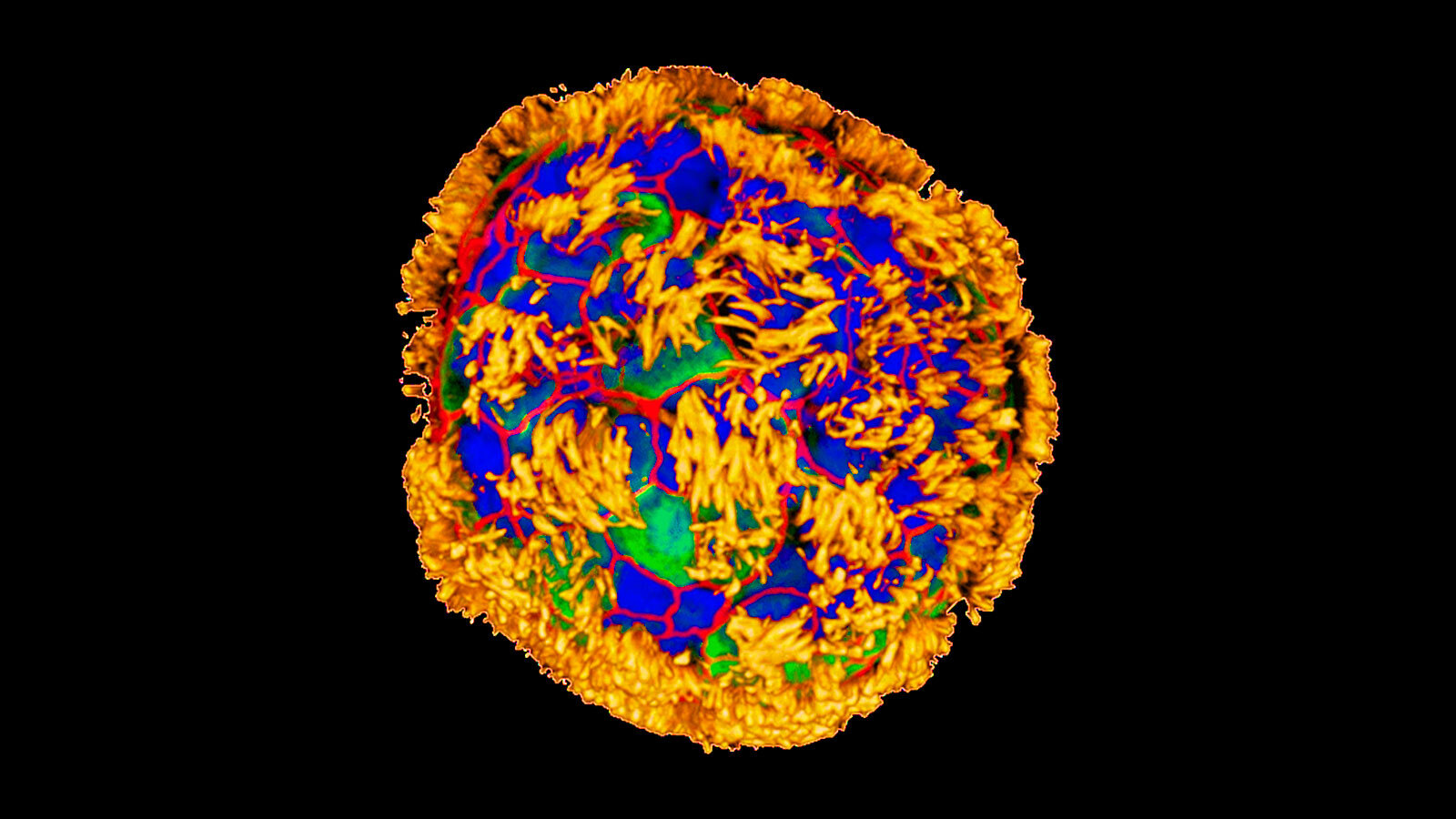

Stem cell biologist Hiromitsu Nakauchi plans to grow a small amount of human cells inside rat and mouse embryos — both of which will be altered so the animals can’t produce a pancreas — for about 15 days. Then, the researchers will bring the embryos to term in surrogate animals. The cells that come from humans are known as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS), which are derived from skin or blood cells and reprogrammed to revert to an embryonic-like state.

The animals would, if successful, use these stem cells to produce a pancreas.

“We are trying to do targeted organ generation, so the cells go only to the pancreas,” Nakauchi told Nature.

In March, Japan overturned a ban on growing human cells inside animal embryos for more than 14 days.

“Finally, we are in a position to start serious studies in this field after 10 years of preparation,” Nakauchi toldThe Asahi Shimbun. “We don’t expect to create human organs immediately, but this allows us to advance our research based upon the know-how we have gained up to this point.”

But some bioethicists are concerned that introducing human cells into other species’ embryos could cause problems.

“It is problematic, both ethically and from a safety aspect, to place human iPS cells, which are still capable of transforming into all types of cells, into the fertilized eggs of rats and mice,” Jiro Nudeshima, a researcher who specializes in the ethical implications of life science research, told The Asahi Shimbun.

An “Uncomfortable and Unstable” Situation for Stem Cell Research

But Nakauchi downplayed these concerns.

“The number of human cells grown in the bodies of sheep is extremely small, like one in thousands or one in tens of thousands,” he told The Asahi Shimbun. “At that level, an animal with a human face will never be born.”

Still, the researchers plan to terminate any experiment if they ever detect that more than 30 percent of the rodent brains are human, per the government’s guidelines. The current experiments are designed to test the limits of growing human cells inside animal embryos. Nakauchi hopes to eventually conduct similar experiments involving pigs, but that will require additional government approval, too.

Increasing the amount of donatable organs could save thousands of lives around the world. In the U.S., for example, approximately 113,000 people were on waiting lists for organ donations in January 2019, and as many as 20 people die each day while waiting for a transplant.