Looking You in the Eye: Disrupting Documentary Filmmaking

I hated the idea, the underlying premise of documentary filmmaking, hated it. Some people may quivel with it but you were given these documentary rules, how non-fiction should be shot. You should use available light; you shouldn’t bring a lot of lights into a scene. You should use the light that’s there. People should never look at the camera. You should be a fly on the wall. You should be observing people from a distance, not interacting with them, observing them and observing them in such a way that you are not controlling what they do.

They’re doing what they’re doing as though you were not even there. I guess for all intents and purposes you could be non-existent or dead.

So here you have these rules, a lightweight camera, handheld camera. You don’t want those big studio cameras. 16-mm; don’t want to shoot in 35. It’s too damn expensive anyway. So here was my idea: have people look directly at the camera. Break the fourth wall. Interact with the people. Instead of pretending to be a fly on the wall, be entirely present in what you’re shooting.

A friend of mine once said you might be a fly on the wall but you’re a 500-pound fly on the wall, which I kind of think is more or less true. Instead of lightweight cameras, use heavy cameras, tripods. Never handheld anything. I would put my head against the lens of the camera. If you know where to look in “Gates of Heaven” you can see my hair on the edge of the frame. My cameraman often would grab the back of my head and pull me back to pull me out of the frame. I wanted to get so close to the lens that you would have that feeling that the person was talking directly to the camera and not to someone just standing next to the camera.

I now call it the faux first person because even if you use a relatively wide-angle lens there’s still that parallax. There’s still that person not looking directly into the lens but looking slightly to the side. And it bothered me for years, even though I kept talking about the first person, first person cinema, direct eye contact. We all know, for example, how important eye contact is in human communication. We may not be staring right into some else’s eyes but we know the minute, the instant that there is a connection based on eye contact. It is wired into our brains. Something happens. Neurological, metaphysical, a combination of A and B.

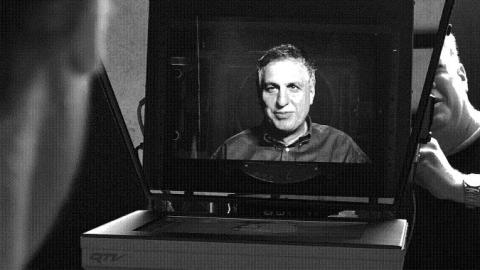

And so in 1990, 1991, I suddenly decided ‘cause the idea had been on my mind for years to build what I call the Interrotron. It was named by my wife who liked the term because it combined interview and terror. And we set it up in a studio in Boston. As you know, it really depends not on one teleprompter but on two. Two cameras, two teleprompters cross-connected. And at first I thought I’ll use one prompter and then it quickly because obvious that’s not going to work.

You actually need this set up, this set up involving two prompters and two cameras. And here’s where I guess for me the trouble begins. I set it up and did this series of interviews. Actually amazing interviews. An interview with Temple Grandin, who had been recently profiled by Oliver Sacks. And interview with Fred Leuchter, who was an electric chair repairman and a Holocaust denier. An odd group of activities.

And three other people. I did five interviews over three days and those interviews became the basis of two films. One, “Mr. Death: The Rise and Fall of Fred Leuchter,” and the other, “Fast, Cheap, and Out Of Control.” I had just released a movie called “A Brief History of Time” based on Stephen Hawkings best-selling book and Philip Gourevitch had written a profile about me for the New York Times Magazine.

A photographer in Nubar Alexanian came to the studio the day that I was using the Interrotron, took a picture, actually it was a picture of George Mendonsa, the gardener who was in “Fast, Cheap, and Out Of Control.” Took a picture and it was a two-page spread in the New York Times Magazine identifying this new contraption that I was using, had really nothing to do with brief history of time. The caption of the article was “Interviewing the Universe.” But it showed the Interrotron and it identified it as the Interrotron. Errol Morris’ interviewing machine.

Well guess what? By the time I realized I should patent this thing, I could no longer patent it because you have exactly one year – be this a lesson to all of you – you have exactly one year from the first public announcement of a device to patent it and if you do not do so you cannot ever do so. The mere fact that the New York Times had run this picture identifying this machine, showing the machine in essence I had a year to patent the device and I don’t think I ever even really started to inquire about a patent until probably 18 months later.