The psychology behind why identical twins inspire fascination—and fear

The twins in Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 film The Shining were never supposed to be identical. In Stephen King’s 1977 book, the Grady sisters are just sisters, eight and 10, and “cute as a button,” at least until spirits and isolation turned their father murderous (you know, just a regular Thursday at the Overlook Hotel). Soon after the book’s rise to the bestseller lists, Kubrick began production on the film, and auditioned numerous young actors to play the sisters. But when identical twins Lisa and Louise Burns waltzed in, they won the part. One of cinema’s greatest auteurs decided there was just something scarier about twins, the twins themselves told the Daily Mail in an interview.

The Burns twins’ turn as the Grady sisters is an iconic moment in a film full of them: “Come play with us, Danny.” Whether he considered it or not, Kubrick was playing with a stereotype that goes back centuries and continues to be a staple of the horror genre today. But what is it about identical twins that make them a subject of both fascination, fear, and oh so many stereotypes? Maybe a better question is what is it about the rest of us that makes this the case?

Between nine and 12 of every 1,000 deliveries produces twins, and around four of those are identical, or monozygotic, twins, according to a recent study in the journal Human Reproduction. Identical twins occur when a single sperm fertilizes a single egg and then splits in two, resulting in two zygotes with the same DNA. There are a lot of factors that make us who we are, but identical twins share the raw material. Why, however, many people find them interesting, unnerving, even scary, says more about general human psychology than it does twins themselves.

Gothic literature scholar Xavier Aldana Reyes of Manchester Metropolitan University wrote about twins in The Conversation, and says that part of what makes fictional twins so potentially frightening is their repetition. He links this to psychology’s definition of the “uncanny,” in which something familiar becomes unfamiliar—and therefore unsettling or creepy. According to Sigmund Freud’s 1919 essay on the term, uncanniness can stem from the “repetition of the same thing.” It’s something that The Shining’s Grady twins, in their matching baby blue dresses and white stockings, play with. There’s a spookiness to when “something that should be the unique, the individual, find[s] a correspondence with the other,” says Reyes. It’s why, in part, mirrors freak us out so much, too.

In the early 20th century, Freud revolutionized the modern understanding of the unconscious mind, and with it “the concern that people weren’t always in full control of themselves, of their actions and thoughts,” says Reyes. That fear manifested in the 19th-century Gothic trope of the doppelgänger—a person’s double, sometimes evil or ghostly, wandering the streets, leading a parallel life.

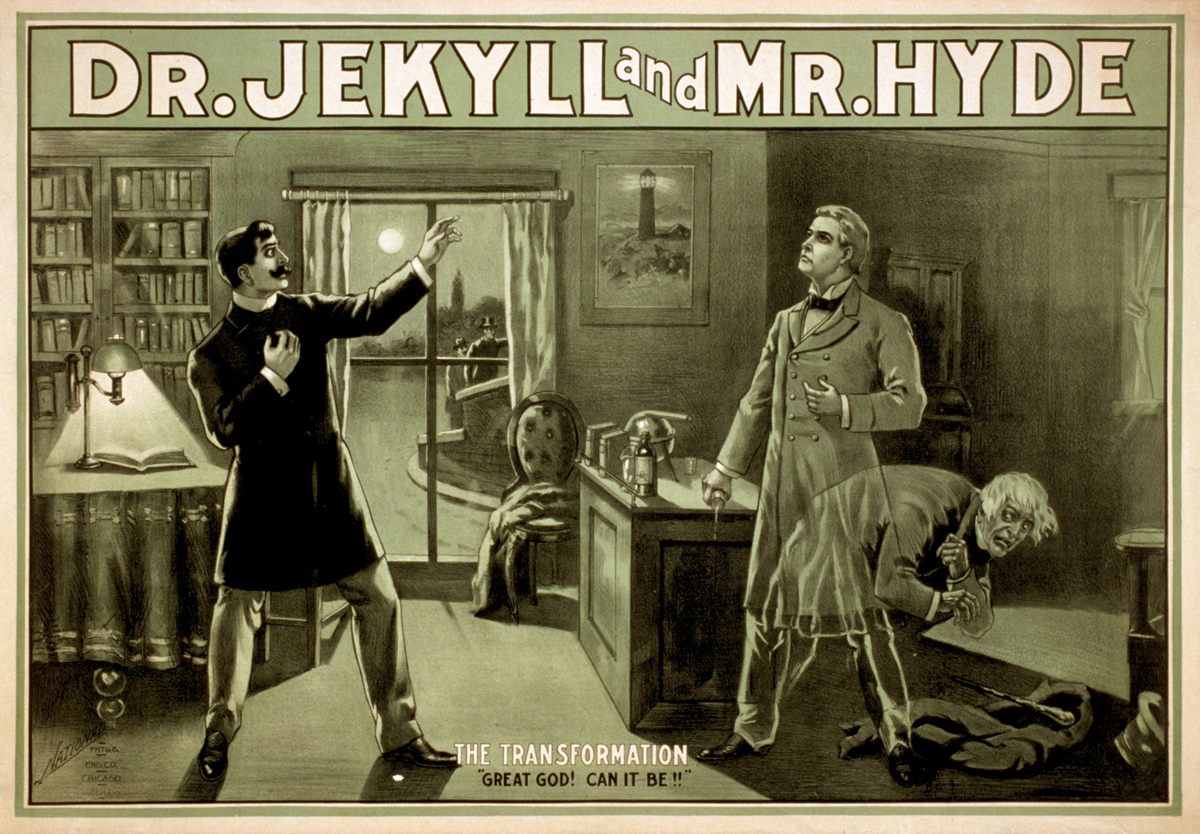

In Gothic literature, the double is “the dark self or the shadow self,” says Reyes. “It’s a personification of everything that the normative, socialized person is not, right? If we’re supposed to be civil, if we’re supposed to be good, if we’re supposed to be mindful, then the double is the selfish, violent, unrepressed side.” Classic characters such as Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, or Yakov Petrovich Golyadkin in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Double, play with this notion. In both stories, a double—not always a twin—wreaks havoc on a person’s life and sense of self.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, twins, particularly identical twins, entered the public eye in new ways, says literature scholar Karen Dillon of Blackburn College in Illinois, author of The Spectacle of Twins in American Literature and Popular Culture. In many scientific studies, twins became test subjects—with one twin serving as a control. Twin studies, as the field is known, emerged in parallel with the American eugenics movement, and was taken to horrific extents by Nazi doctor Josef Mengele. “Every major eugenics textbook has chapters on twins,” says Dillon. This fascination with and experimentation on twins often had the effect of othering them, distancing them from their own humanity. They were not people, exactly, but test subjects—as well as objects of curiosity, even sideshow attractions, which is true especially for conjoined twins (all of whom are monozygotic).

“Those two histories of twins that run parallel, to me, inform all our popular understandings of twinship—twins as freaks, and twins as unique and strange,” says Dillon.

The horror genre has long remixed and rehashed these tropes. One of the most common is the good twin/bad twin dichotomy. “The twins’ subtle differences create a happy/sad, good/bad, Jekyll/Hyde reading,” writes Dillon. Like with the double, the good/bad twins come to represent “two different sides of the same individual,” she says.

There’s often no explanation behind why one twin might be evil and the other not, says Dillon. “The evil of one twin just sort of emerges,” without explanation. The good/bad twin suggests “we can just be born evil because with twins, of course, they’re growing up in the exact same environment so they’re supposedly treated the exact same way.” Evil, therefore, is something beyond understanding or explanation.

In films, identical twins are often used in similar ways to Gothic literature’s doubles. As with the double, twins can express “the divided notion of the self,” says Reyes—that “there is no such thing as a holistic, coherent self.” In films, one actor often portrays both twins, such as Jeremy Irons in Dead Ringers or Margot Kidder in Brian De Palma’s 1972 Sisters. Using the same actor “creates a form of the visual uncanny that novels can only hope to recreate through your imagination,” says Reyes. Identical twins become a visual shorthand in film of the divided self—the evil self and the good self.

Another common trope, writes Dillon, is “twins’ shudder-inducing closeness.” Twins’ “insularity,” she says, stems from this sense of “two people who can be this whole world for each other. You know, twins in pop culture often communicate psychically or have their own sort of twin language or don’t need to communicate at all. They just seem so insular that no one can penetrate that relationship.”

Twin stereotypes are so entrenched that Dillon, an identical twin herself, remembers, “Every time I came across twins in pop culture, I was sort of like, ‘Oh god, the same representation of twins over and over.’” Growing up, many of those stereotypes informed how friends and family saw her and her sister. “I would be rich if I had a dime every time someone asked us, ‘Do you ever switch classes and trick your teacher? Can you read each other’s thoughts? Do you have a secret language?’” She says, “I even had uncles who were like, ‘Are you Karen or Carol? Oh, it doesn’t really matter.’

“It does wreak havoc with your psyche, honestly,” she says.

Victoria Morrell, mother of two pairs of identical twins and the communications officer at Twin Trust, an English charity that supports parents of twins and multiples, says raising twins is no easy task. “I always get asked which one is the naughty one,” says Morrell, but “it’s not really anything like that.”

“Growing up as a twin is a unique social context,” says Dillon, one that can make it difficult to define your own individual identity. While twin stereotypes can be “fun,” she adds, they also “can take a toll.” Both Morrell and Dillon would like people to treat twins as individuals. After all, Dillon says, “Twins are two people, two individuals who just happened to have shared a womb.”

This article originally appeared on Atlas Obscura, the definitive guide to the world’s hidden wonder. Sign up for Atlas Obscura’s newsletter.