How suicide warped David Foster Wallace’s legacy

- Infinite Jest author David Foster Wallace died by suicide in 2008.

- His tragic fate made him even more famous but arguably turned him from a countercultural figure into a cultural commodity.

- Many people now read Wallace’s work through the lens of his death, to the frustration of some scholars.

On the evening of September 6, 2008, David Foster Wallace convinced his wife Karen Green to go to the mall without him. Green was hesitant to leave her husband alone, as he had been struggling with his mental health for some time. Still, the fact that he had recently gone to the chiropractor seemed like a sign that things were under control. “You don’t go to the chiropractor if you’re going to commit suicide,” she told herself and went out the door.

Unfortunately, her assumption proved wrong. Once his wife was gone, Wallace wrote a two-page note and placed it next to the neatly arranged manuscript of his nearly complete novel The Pale King. He then walked out onto the patio of their home in Claremont, California, stood on a chair, and hanged himself. “This was not an ending anyone would have wanted for him,” author D.T. Max later wrote in his 2012 book Every Love Story is a Ghost Story, a Life of David Foster Wallace, “but it was the one he had chosen.”

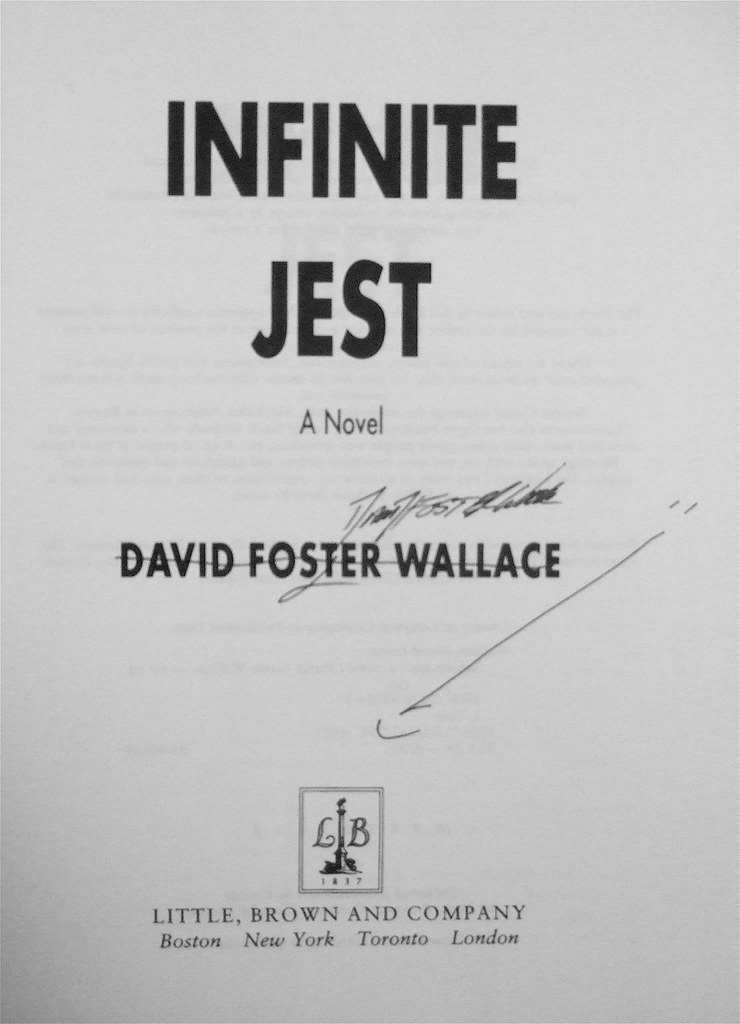

Wallace grew up in Illinois, raised by a philosophy professor and English teacher who said “3.14159” instead of “pie” and made up words for things the dictionary had yet to give a name. He was a prolific student and avid tennis player, making up for lackluster athletic skills with an ability to calculate how the Midwestern winds would alter the trajectory of his strokes. These and other youth experiences he describes with dizzying detail in Derivative Sport in Tornado Alley, one of many he wrote for Harper’s Magazine, eventually compiled into a collection titled A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again. His fiction performed better still. “I am delighted to be in at the start of a brilliant career,” said the literary agent who took on his first novel, The Broom of the System, starting a partnership that would lead to the 1996 publication of Infinite Jest, Wallace’s best-selling magnum opus and one of Time magazine’s 100 best English-language novels published between 1923 and 2005.

Behind the scenes, however, Wallace’s accomplishments were overshadowed by his many mental health issues. As with so many other giants of world literature, the qualities that made him an astute and driven author — perfectionism, self-consciousness, and sensitivity — also hindered his ability to cope with the everyday challenges of being alive. Diagnosed with depression during his undergraduate years at Amherst College, he spent most of his adult life on Nardil, an antidepressant still available in the US today, but which has been discontinued in many other countries due to its many side effects.

In Wallace’s case, the prescription not only upset his stomach but also — or so he was convinced — diminished his creativity. Hoping to overcome writer’s block, he stopped taking Nardil in the summer of 2007. He entered this new phase of life with “a sense of optimism and a sense of terrible fear,” author Jonathan Franzen, who was friends with Wallace, told The New Yorker.

Forever young

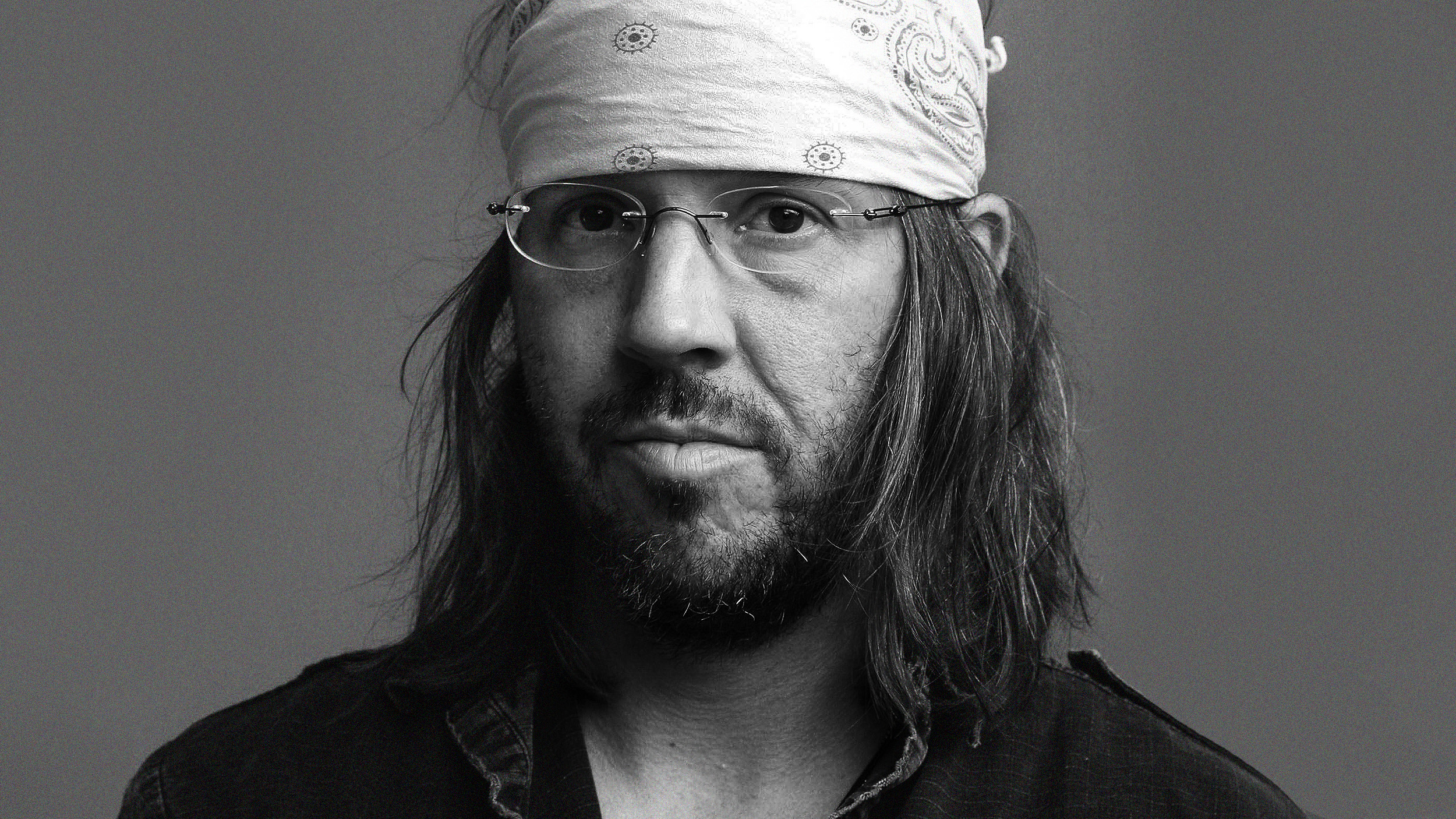

If Wallace had been a popular author before his death, news of his passing — and the tragic circumstances surrounding it — turned him into a veritable celebrity. Once read almost exclusively in the US, his following expanded across countries and continents. His former homes in Boston and Bloomington have become shrines for literary pilgrims, and his silhouette — his bandana and uncut rock-and-roll hair — is almost (almost) as recognizable as that of Che Guevara. Meanwhile, screen adaptations like The End of the Tour, starring Jason Segel and Jesse Eisenberg, have introduced him to a wider audience that may have been too daunted or disinterested to read his hefty books.

Wallace obviously owes a large part of his fame to his talents as a writer. His style was as idiosyncratic as they come, combining street slang, scientific prose, jargon, and everyday speech into sentences that can span as much as half a page – a style which, despite numerous attempts from devotees, simply cannot be replicated. He’s also notorious for using copious amounts of footnotes, a feature normally found in academic papers, stuffing in the kind of digressions and meta-commentary that most editors would urge their writers to remove.

“He always struck me as someone who was in the tradition of maximalism,” David Hering, a fiction writer and author of David Foster Wallace: Fiction and Form, tells Big Think, comparing him to James Joyce and Herman Melville. “But he was writing about my generation, and particularly the omnipresence of mediated versions of the self, and how that created this novel version of self-consciousness. He was drawing from a long tradition, but spoke to the world I was living in.”

That said, part of Wallace’s larger-than-life status can also be attributed to his premature death. “He died young,” notes Geoff Ward, a British scholar of American literature who wrote a BBC radio documentary about Wallace’s life and work titled Endnotes. “There is no long decline, and he left us effectively in mid-sentence. He will be forever young, and always liked by younger readers who are looking for something that matches in intensity both their promise and self-doubt.”

What Wallace himself would think of his posthumous fame is difficult to say. “The whole going around and reading in bookstores thing,” he told an interviewer in 2003, when he was still riding the waves of Infinite Jest, “it’s turning writers into kind of penny-ante or cheap versions of celebrities. People aren’t usually coming out to hear you read. They’re coming out to sort of see what you look like, and see whether your voice matches the voice that’s in their head when they read. None of it’s important. It’s icky.”

Although his biographers concede that he craved attention and approval, and carefully tailored his bro-y public persona to this end, they also agree that his fate — his transformation from a countercultural figure into a cultural commodity, swallowed and flattened by the same consumerist machine he sought to dismantle — would have disturbed him.

Certainly, the prevailing singular image of Wallace fails to capture the contradictions and multitudes contained within his work. Ward insists that he does not embody a fixed set of values and characteristics but that his career was marked by curiosity, experimentation, and a never-ending search for a belief system that wouldn’t crumble under scrutiny. “Otherwise,” he says, “there wouldn’t be a book about rap, or a book about John McCain. At one point, he was apparently on the verge of converting to Roman Catholicism. There’s the stoned DFW, the DFW who could have been a philosopher (maybe he is one, using fiction as his chosen rhetorical armory), the Midwest hayseed, wide-eyed youngster, the epically complex postmodernist…Many foxes, all fleet of foot.”

“He’s become a cultural shorthand,” adds Hering, “the bro-y writer, prodigious footnoter, over-writer. All of these things are present in the work, but because of the necessity of the broader culture, they’ve been magnified into a small, easily digestible number of identifying markers. The thing about this reductiveness is that it works against the form of the work itself, which is often about the complexity of a social or psychological problem, and how it can’t necessarily be broken down into binaries.”

David Foster Wallace as tortured artist

Wallace’s tragic death not only bolstered his fame but also led to a concentrated and arguably misguided effort to medicalize his writing, to search his work for clues of what was yet to come. Although Wallace never spoke openly about his own mental health, he of course drew from personal experience for inspiration, and themes of depression and anxiety show up in almost everything he worked on. “Paxil, Zoloft, Prozac, Tofranil, Wellbutrin, Elavil, Metrazol,” he wrote in Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. “None had delivered any significant relief from the pain and feelings of emotional isolation that rendered the depressed person’s every waking hour an indescribable hell on earth.”

Broom of the System follows a young woman who thinks she exists only as a character inside a story, questioning the authenticity and futility of her own existence. Infinite Jest, whose title refers to a movie so compelling that those who see it will watch it on repeat until they die, is largely about addiction — to entertainment, substances, and even addiction itself. A large portion of the novel centers on residents of a Boston chapter of Alcoholics Anonymous, an organization Wallace himself joined in the hope that it would not just help him recover from his various dependencies, but also — to the chagrin of administrators — defeat the demons that had driven him to substance abuse in the first place.

Mental health does not just factor into what Wallace wrote about, but also why he took up writing in the first place. Far from writing for entertainment — his own or his audience’s — he came to the profession in search of answers. “Fiction,” he said, is “about what it is to be a fucking human being,” adding he hoped his work would help readers “become less alone inside.” For all his disparate interests, he repeatedly came back to the concept of consumerism, criticizing not just corporations, but also the human weakness they take advantage of: the hope to find fulfillment through external means, be it a Whopper or a Lamborghini.

Tempting though it may be, many scholars caution against reading Wallace in this way. “His suicide,” says Ward, “was not just a personal tragedy, but an excuse for bio-criticism to medicalize his alienation from various cultural norms. This does him a disservice. The manner in which he left his bodily life shouldn’t be allowed to overshadow the life of his writing.”

Like Ernest Hemingway or Leo Tolstoy, David Foster Wallace has come to be seen as a tortured artist – a stereotype that, in addition to simply acknowledging an author’s mental health issues, professes that these issues are intimately tied to their creative genius. Researchers have long cautioned against this narrative, noting that conditions like depression deteriorate people rather than empower them, and those who study Wallace’s work in detail generally share the same sentiment.

“For all the great passages in Pale King,” concludes Ward, “his depression was beginning to impact his writing by coarsening it and making it less brilliant, more sluggish. I can’t help but wonder if he saw this himself, and whether that contributed to his personal tragedy. On the other hand, when they found him, he had arranged the manuscript of Pale King in a prominent and lit position on the table, clearly signaling that he thought it should be saved. Reviewers of the finished novel would have said, this is good — but not quite as good as Infinite Jest — and so the pressure would have been on the next novel, which we’ll never have.”