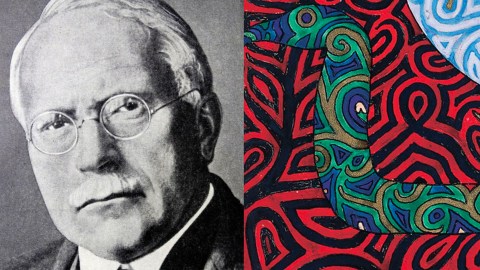

In “The Red Book,” Carl Jung recorded his encounters with entities from “inner space”

- In The Red Book, psychiatrist Carl Jung documented his personal explorations into the depths of his mind through vivid daydreams and visions.

- Jung believed the human psyche includes a personal unconscious and a collective unconscious, which he described as a universal, inherited layer of the mind that houses universally shared patterns or symbols called archetypes.

- While not a scientific pursuit, the results of his experiment are fascinating.

One day, sometime between 1913 and 1917, the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung followed a wise old man up a rocky ridge until they reached a structure that resembled Stonehenge. At the center of this structure stood an altar. On that altar stood a house. From the doorway emerged a doll-like woman whom Jung recognized as Salome, the stepdaughter of Herod Antipas who, after dancing for him on his birthday, had asked for the severed head of John the Baptist.

Salome saw Jung and began to worship him. When Jung asked why she was worshipping him, she replied: “You are Christ.” As she uttered these words, a black serpent coiled its body around Jung’s, completely enveloping his heart. Suddenly, it dawned on Jung that he had assumed “the attitude of the Crucifixion.” He looked at the wise old man, who was in fact the Biblical Elijah. “Why, it’s just the same, above or below,” Elijah said. Then Jung’s face changed into the face of a lion.

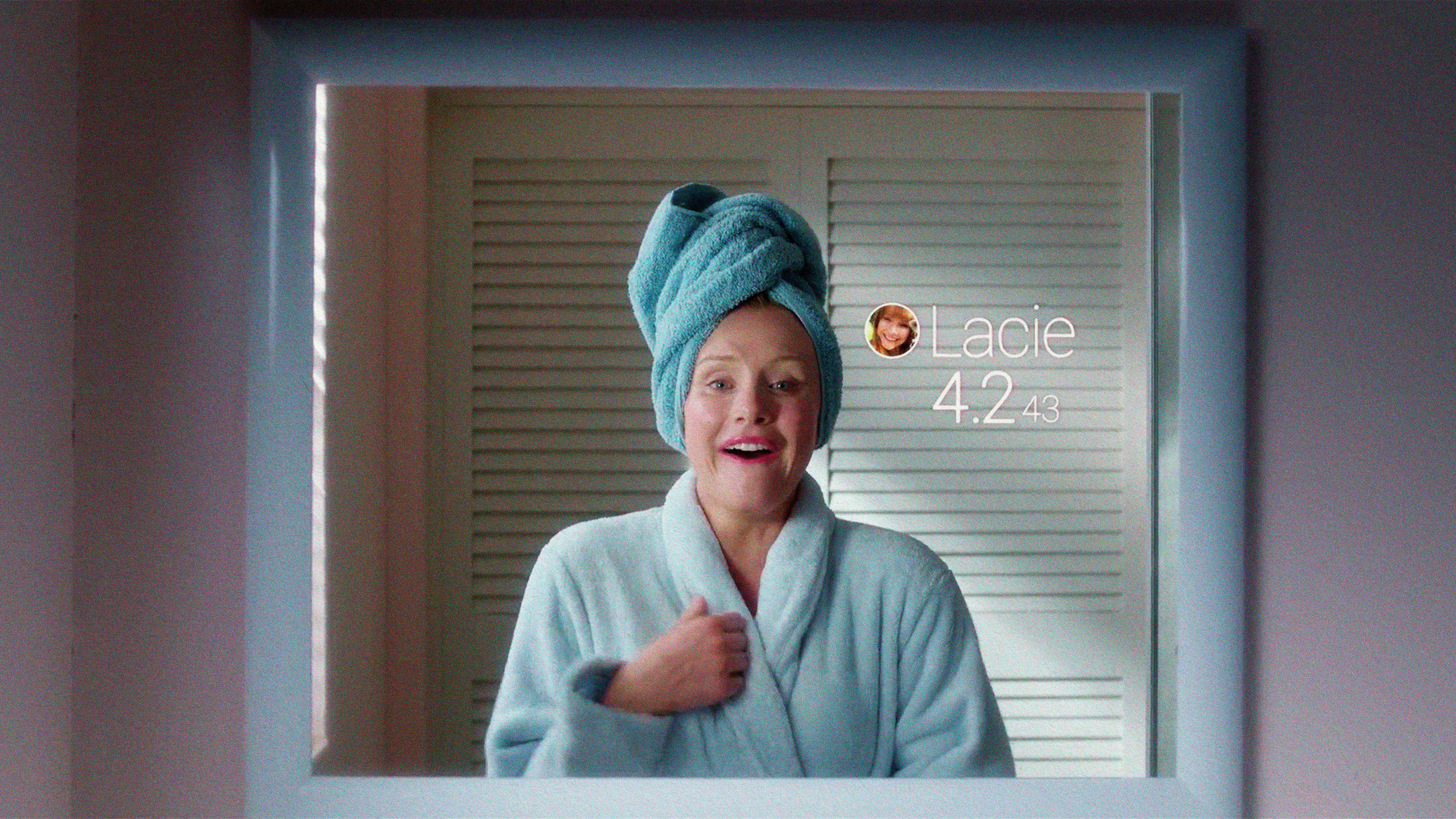

The above may sound like a dream, but it wasn’t. It was a daydream, one Carl Jung experienced as part of what he later referred to as the “most difficult experiment” of his career. In an effort to consciously observe the machinations of his unconscious mind, he spent years conditioning himself to let his imagination run wild. He eventually compiled his observations into a red leather manuscript known as The Red Book: Liber Novus or New Book, which wouldn’t be officially published until 2009.

Despite its relatively short lifespan, The Red Book has already established itself as the most controversial and unorthodox text in Jung’s entire body of work — and that’s saying something. Even more so than Sigmund Freud — who was Jung’s friend and collaborator before the two had a falling out — Jung’s once-groundbreaking ideas about the human mind have been heavily scrutinized by modern psychologists, many of whom label Jung’s ideas as unverifiable at best and pseudoscientific mysticism at worst.

Carl Jung, in his defense, openly admitted that he resorted to unscientific means — the combined realms of literature, mythology, and theology — in an attempt to explain what reason and technology could not. Although The Red Book shouldn’t be confused with academic studies containing quantifiable data, there is a method to Jung’s madness, one that makes sense when placed in the broader context of his theories about archetypes and the psychological dimensions of organized religion.

The collective unconscious

To understand Carl Jung’s Red Book observations, you must first understand his concept of the collective unconscious. Unlike many other Western thinkers, who presume the mind of a newborn baby is a blank slate, Jung believed that this slate comes imprinted with a rough sketch — a universal layer that is inherited as a product of human evolution, not developed through personal experience.

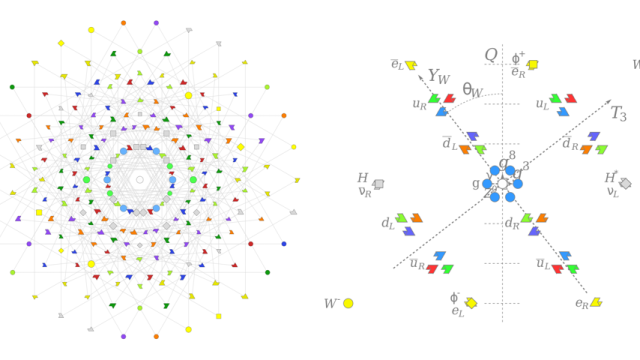

Jung believed that the collective unconscious exists independently of individual consciousness and is common to all human beings. It contains archetypes, which are universally understood patterns or symbols shared among individuals across cultures and ages. These archetypes act as psychological blueprints that shape how we understand and respond to the world around us. They influence our perceptions, behaviors, and emotional reactions, and are expressed through myths, religions, dreams, and other cultural phenomena.

In The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Jung wrote that the collective unconscious guarantees “in every single individual a similarity and even a sameness of experience and also of the way it is represented imaginatively.” According to Jung, this would explain why so many geographically isolated civilizations ended up incorporating suspiciously similar symbols and themes — archetypes — into their art, oral traditions, and even dreams. (Exhibit A: the flood myth from the Book of Genesis.)

These archetypes — which range from catastrophes to caring mothers — are sometimes referred to as “psychic organs,” as a helpful analogy. Just as physical organs achieve homeostasis inside the human body, so do psychic organs maintain balance inside the human mind. But while the functions of physical organs can be measured by outside observers, psychic organs are best investigated through direct experience. This was true in Jung’s time and arguably still is today.

To investigate archetypes, Carl Jung aimed to switch off his conscious mind and see what came up in his thoughts. Jung ventured so deep into his unconscious that he had conversations with figments of his imagination, who appeared — as in dreams — to be autonomous entities, possessing knowledge he did not consciously possess. Jung’s biographer and friend, Barbara Hannah, said he “made it a rule never to let a figure or figures that he encountered leave until they had told him why they had appeared to him.”

Inner space

“An incessant stream of fantasies had been released,” is how Carl Jung described the experiments in his autobiographical text Memories, Dreams, Reflections. “I stood helpless before an alien world; everything in it seemed difficult and incomprehensible.” But Jung was no ordinary lucid dreamer; armed with both general and specialized psychiatric knowledge, he aimed to figure out exactly what this other, unknowable part of himself was attempting to tell him.

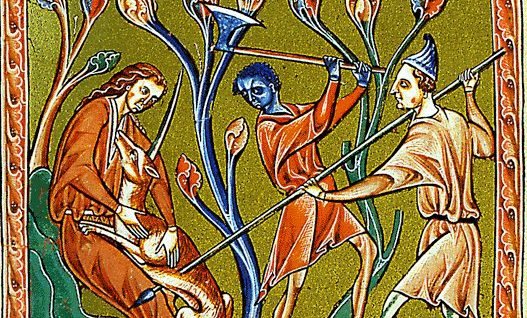

In one “vision,” Jung found himself high in the mountains where he saw none other than Siegfried, blowing his horn and riding a chariot made from bones. “We knew that our mortal enemy was coming,” Jung later recalled in a lecture. “We were armed and lurked beside a narrow rocky path to murder him.” Jung thought his hostile encounter with the hero from German and Nordic folklore, which preceded a vision of the birth of a child from Jung’s “own soul,” symbolized his old hero archetype being replaced with another.

The more comprehensive analyses of Jung’s unconscious mind have come not from Jung himself, but from Jungian scholars mulling over the recordings of The Red Book. Lionel Corbett interprets the previous vision as an illustration of his conscious belief in Friedrich Nietzsche’s famous statement that God — the Christian God — was dead, and that he needed to be replaced with a different source of meaning lest the collective unconscious collapse and society spiral into nihilism.

Corbett’s interpretation also applies to the vision where Jung was told that he was Christ and imitated the Crucifixion. He notes that the two individuals accompanying Jung in this vision — Elijah and Salome — both played a conservative role in the history of religion: Elijah refused to acknowledge any God-image other than Yahweh, while Salome killed the person who heralded Christ’s divinity. Christianity was of great concern to Jung, for he believed it had kept the collective unconscious under control.

The reception of The Red Book reflects the reception of Carl Jung in general. The text has left a minor imprint on scientific literature, reinforcing the notion that its interdisciplinary author leaned closer to the humanities than the sciences. Jung’s views on religion also generated criticism, with some accusing him of turning his personal brand of New Age spirituality into a cult — accusations that Jung denied. Others still accused him of madness — accusations he accepted, if only because the unconscious is an inherently mad place.