How the “Holy Grail” of audio technology rescued a 1964 Beatles performance

Credit: United Press International / Public domain / Wikimedia Commons

- In 2009, Abbey Road software engineer James Clarke began developing ways to separate audio elements on finished mono and stereo recordings by the Beatles.

- To isolate the band’s instruments on a performance crudely recorded live at the Hollywood Bowl in 1964, he developed an algorithm which assisted the audio separation process.

- The cleaned-up audio “stems” were then remixed at Abbey Road studios.

Our feelings about how things work in a recording studio are similar to our feelings about how things work on the training pitch at an elite football club. In both cases most of us will never be in a position to witness how this particular form of human interaction operates. In the absence of direct experience we combine our feelings about music — that it’s a matter of divine spark occurring between human beings with a shared purpose — and our feelings about people — that they are at their best when they are happy and inspired — to create a picture which satisfies our need to be emotionally invested in its making. In that sense, what Abbey Road represents in its position as the best-known and, from certain angles, the last recording studio in the world is a whole way of feeling about music.

Music remains the same thing it always was. It’s the records that are always changing. For most of the 90-plus years since Abbey Road opened its doors, those records were clearly finished with once they were done. In the last 20 years powerful forces — the appetite of the pop market for endless alternative mixes of the tiniest successes, pressure from the producers of movies and video games for music they can play with, the archaeological instincts of the people who crave nothing more than a boxed set of things they have heard a million times before, and the irresistible power of whatever happens to be the latest toy — have combined to change all this.

James Clarke is a New Zealander who started working at Abbey Road as a software engineer. Because he came from this kind of background he was more prepared than most to regard everything he dealt with as scientific rather than emotional information. To that end he was talking to sound engineers in the canteen at Abbey Road one day in 2009 and asked whether it would be at all possible to take mixed recordings and, so to speak, “demix” them. What he was wondering was whether it would be feasible to take classic records, which had been recorded on two or four tracks and then mixed down into one mono track, and in some way separate them into their constituent parts. They laughed, saying this was the Holy Grail of sound recordings and couldn’t possibly be done. Once a multi-track recording had been mixed down to either a mono or stereo version there was no way of unmixing the paints. The best you could hope is that you could go back to the unmixed tapes, if such things still existed and had survived the hurly burly of corporate takeovers, and that was very unlikely. During the seventies and eighties nobody at record companies had ever thought they might be dealing with heritage assets.

James Clarke was not dissuaded. He reasoned that if an acute human ear could hear separate instruments on a recording it ought to be possible to develop a program which could similarly separate them. He first applied his work on the proposed re-release of The Beatles At The Hollywood Bowl. This was a live recording that had been made in 1964 when the screaming was at its height.

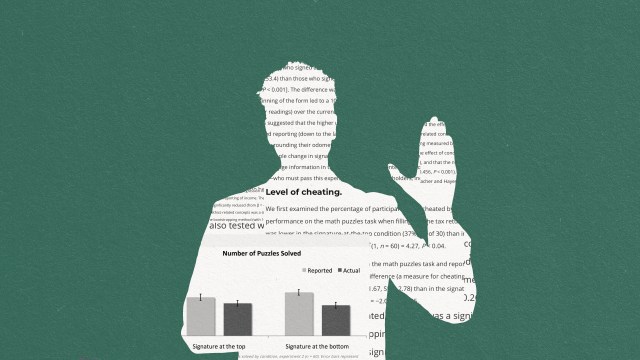

Furthermore, American union restrictions meant that George Martin had no role in deciding what got recorded and how. The result was a recording that was high on excitement but low on musical value. Clarke set to work. By looking at the signal as a spectrogram he was able to visually identify the vocals, the different instruments, and the screams. He could see where each fell on the spectrum. Then, by treating the screams as though they were just another instrument, he was able to reduce them in the mix. He was able to put them in the background of the mix, bring the group to the front, and change the picture the sound presented.

The further he got into this new field the more he began to speak of deep learning, neural networks, and non-negative matrix factorization.

This was the appliance of science to the suck-it-and-see world of record production. The further he got into this new field the more he began to speak of deep learning, neural networks, and non-negative matrix factorization. He set himself the task of isolating the single element that is George Harrison’s Gretsch Country Gentleman from the elixir of life that is “She Loves You.” To do this he modeled hundreds of different performances of the song in order to accurately plot the dynamics. In the course of this he discovered that once the Beatles had recorded a song they didn’t stray far from it in performance. He then developed an algorithm which could read these performances and separated the original instruments into tracks, now given the medical-sounding term “stems.” Once he had Harrison’s part it took him nine months to clean it up a few seconds at a time. A piece of Roman marble unearthed on a historical site could not have been more painstakingly brought into the light. Having done this, he played it once more into Studio Two and then recorded the results as though the very air in that by now sacred room would impart some quality to it which nothing else could.

Clarke unveiled the results in the course of a lecture at Abbey Road in 2018. His audience were the kind of people who are drawn to a technical lecture at a recording studio. The reaction underlined that Beatles scholarship is now as schismatic as Judaean politics in Life of Brian. Some accused him of having spoiled his case by using a version of George’s solo from the German-language version of “She Loves You.” The muttering continued in a million forums.