Is wasp venom the next healthcare revolution?

(Photo by Dr. Peter J Bryant/University of California, Irvine)

- Researchers are looking at the venom of wasps, bees, and arachnids to develop life-saving medical therapies.

- Researchers at MIT created synthetic variants of a peptide found in wasp venom that proved an effective antibiotic.

- With the “post-antibiotic era” looming, synthetic peptides could provide a way to maintain global health initiatives.

Two of the most common phobias are the fear of insects and fear of needles, so it’s little wonder that people with apiphobia and spheksophobia aren’t keen for bees or wasps. These little critters mix both elements and add a dash of caustic venom. However, the pain-inducing liquid is brimming with helpful molecular mixtures that scientists are just waiting to unlock.

Compounds from venom have been used, for example, to create painkillers, reduce blood pressure, and even detect explosives. Earlier in December, MIT engineers added to this laundry list of venomous blessings when they announced they had devised a way to turn wasp venom into an antibiotic. It is research that could have far-reaching effects for the future of healthcare.

A Polybia wasp nest in Pantanal, Brazil isn’t the type of place one would expect to find a promising antibiotic.

(Photo from Wikimedia)

A peptide a day

The venoms of bees, wasps, and arachnids contain compounds called antimicrobial peptides (AMPs). As the name suggests, these peptides don’t get along with microbes such as bacteria, making them promising therapeutic agents. Unfortunately, being part of the venom cocktail, they can be less than salubrious in their natural form. The goal, then, is to devise a method to adapt an AMP so it continues to fight bacteria but does no harm to human cells.

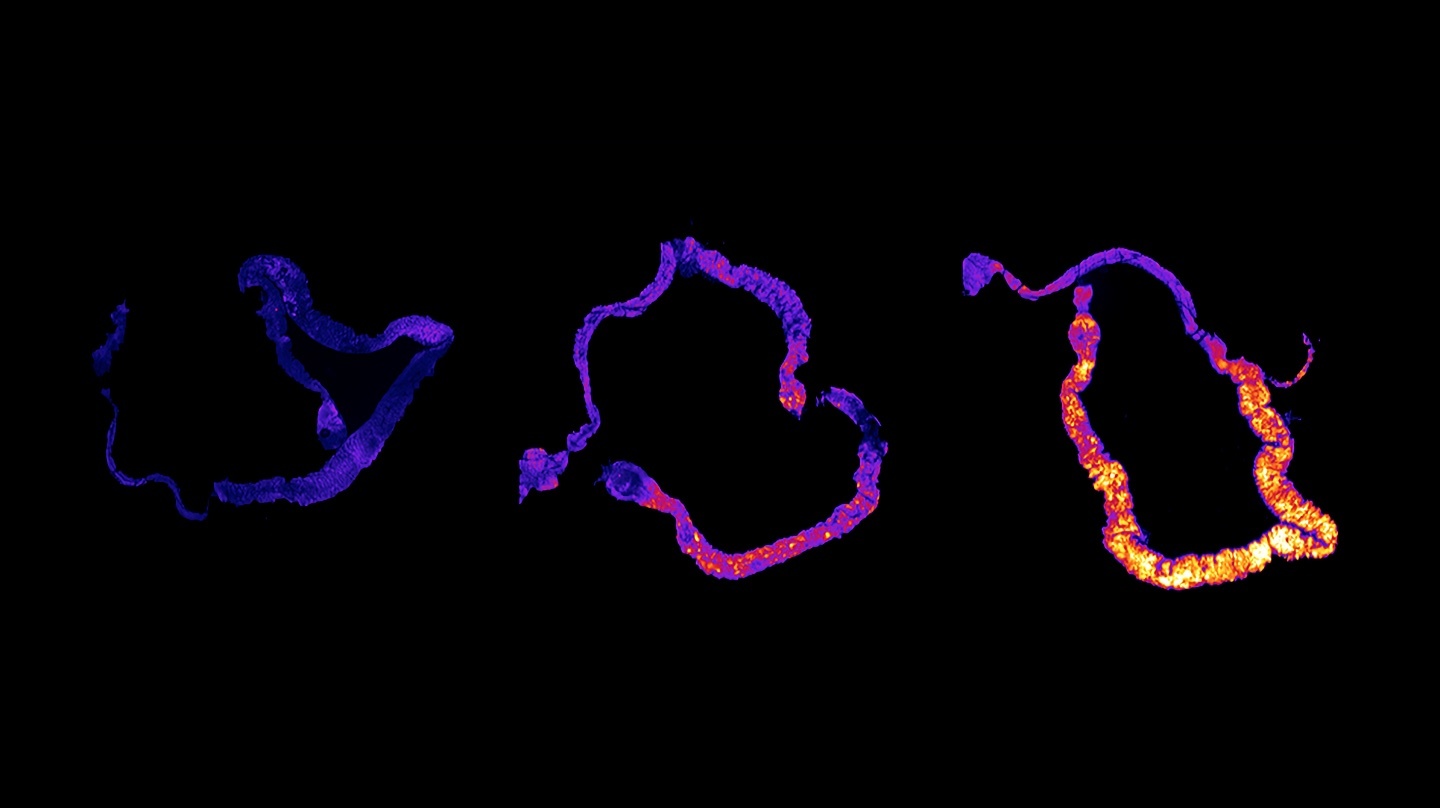

Researchers at MIT looked toward an AMP found in the venom of the Polybia paulista wasp. Called polybia-CP, it weights in at a mere 12 amino acids, shrimpy by even peptide standards. This made it easy (well, easier) for the researchers to see how their engineered changes altered the AMP’s alpha helical structure and its hydrophobicity, features that determine how it interacts with cell membranes.

“It’s a small enough peptide that you can try to mutate as many amino acid residues as possible to try to figure out how each building block is contributing to antimicrobial activity and toxicity,” César de la Fuente-Nunez, MIT postdoc and senior author on the paper, told MIT News.

After testing a dozen variants on bacteria and fungi, the researchers took the most promising ones to test in mice afflicted with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a pathogen known for being resistant to multiple antibiotics. The synthetic peptide sterilized the infection, demonstrating its potential as an antibiotic. Further, monitoring the mice’s body weight confirmed its lack of toxicity.

“After four days, that compound can completely clear the infection, and that was quite surprising and exciting because we don’t typically see that with other experimental antimicrobials or other antibiotics that we’ve tested in the past with this particular mouse model,” De la Fuente-Nunez said.

De la Fuente-Nunez — along with fellow senior editors Timothy Lu (MIT associate professor) and Vani Oliveira (associate professor at Federal University of ABC), and lead author Marcelo Der Torossian Torres (also from MIT) — published their work in the December issue of Communications Biology.

A global life saver?

Anti-microbial-resistant (AMR) pathogens are a growing threat to global health. The World Health Organization has called AMRs an “increasingly serious threat to global public health” and one that “requires action across all government sectors and society.” These so-called “superbugs” are responsible for 700,000 deaths annually worldwide. That number could leap to 10 million by 2050.

Without intervention, AMRs could stymie the progress we’ve made against virulent diseases and prevent WHO from achieving its Sustainable Development Goal #3: Good Health and Well-Being.

If researchers can develop antimicrobial peptides into non-conventional antibiotics, they could stave off the “post-antibiotic era” and save thousands of lives. There is still a lot of research to be done, but studies like those from MIT show promise at being able to combat resistant pathogens, such as the aforementioned Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

“Overall, AMPs offer promising alternatives to standard therapies as anti-infections and immunomodulatory agents with mechanisms of action which are less prone to resistance induction compared to conventional antibiotics,” noted a review on the current research into AMPs (emphasis mine). While the review acknowledged existing challenges for repurposing candidate AMPs into successful therapies, it also predicted an acceleration of advances as our understanding grows.

While it’s doubtful this research will make anyone afraid of wasps any less afraid, they may be a little more thankful that these critters are in the world and helping scientists develop life-saving medicines. So long as they keep a respectable distance.