Supercentenarian DNA May Hold the Ultimate Secret to Longevity

Better food, healthcare, working conditions, and safety protocols have allowed humans to live longer and healthier than ever before. In most developed countries today, the average lifespan is 80 years, while in 1906, a little more than 100 years ago, it was 48. Projections moving forward look so good that there’s a debate in the medical community on whether or not we can increase human longevity indefinitely.

There are far more centenarians than ever, or those who’ve lived to 100, and more supercentenarians or those 110 or above. A study published last year in the journal Natureproposes that 122 may be the human lifespan’s ceiling. Most of those in the upper reaches of our lifespan assign their longevity to lifestyle choices or healthy habits, which of course play an enormous role. But many scientists believe important secrets to longevity lie within our genes as well.

Moreover, quite a number of studies suggest a strong genetic link. For instance, a 1996 study published in the journal Human Genetics, looked at thousands of Danish twins. It concluded that 20-26% of longevity is up to one’s genetic code. Meanwhile, a Boston University study found that a centenarians’ siblings have about a 3½ times higher chance of reaching 100, over non-centenarians’ siblings.

What’s more, supercentenarians don’t often experience any of the serious diseases people succumb to in old age, such as heart disease or cancer. Turns out, the longest living among us carry fewer of the genetic variations involved with such diseases.

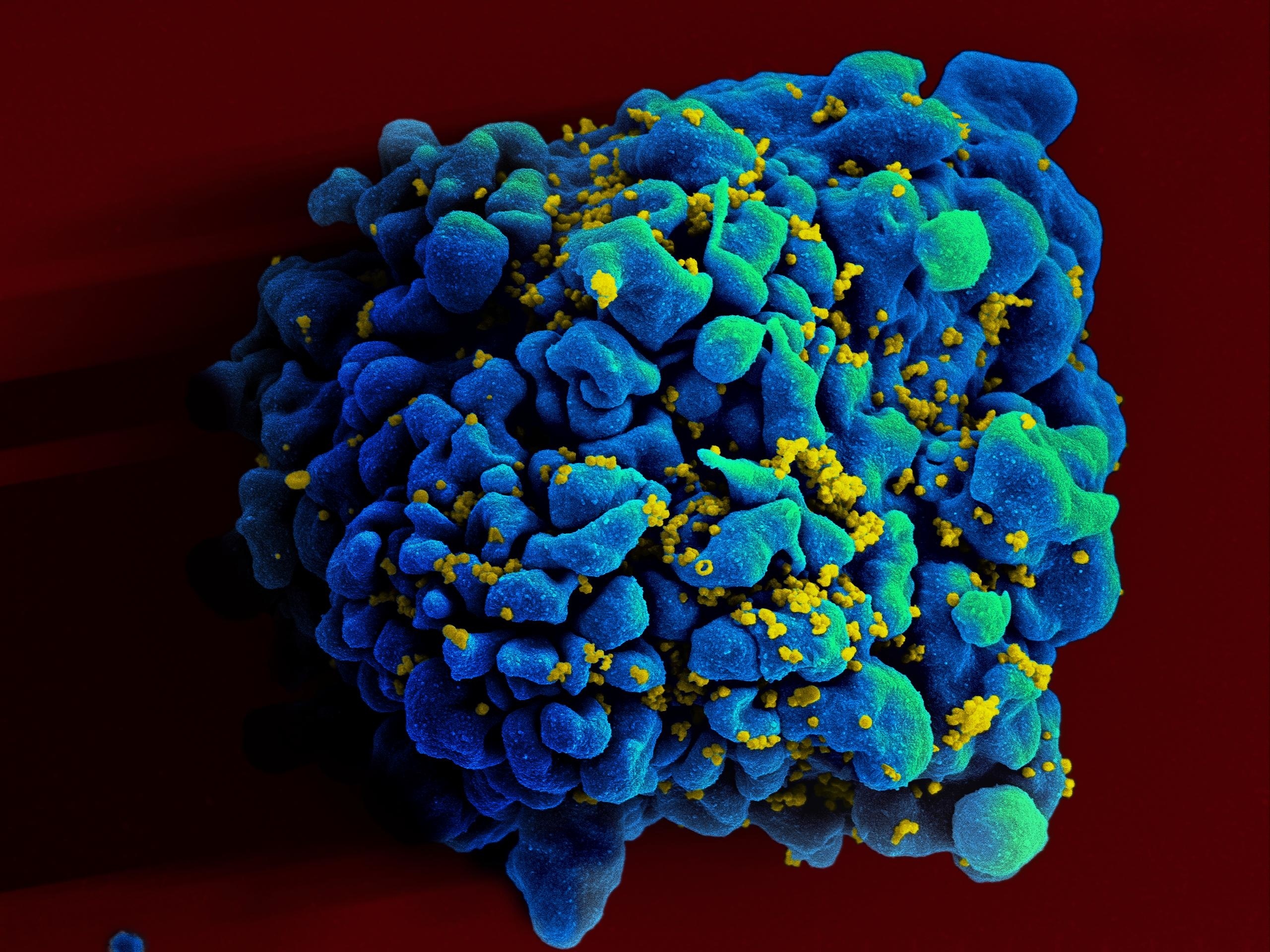

While lifestyle plays an enormous role, certain genes or gene combinations add significantly to longevity and good health later in life. Credit: Getty Images.

To find out what all those who’ve reached 110 have in common, a nonprofit known as Betterhumans is studying the DNA of those who have shown impressive longevity. It bills itself as “the world’s most comprehensive genomic study of supercentenarians and their families.” DNA samples collected will not only be sequenced, the data produced will be made available to the public. In fact, a series of genomes are to be released this week.

The idea is to find out what genes gives people an exceptional lifespan, synthesize those genes, and from there develop a way to prolong life and health in others. So far, the project has collected over 30 samples from people in North America, Europe, and the Caribbean. Those who qualify can donate their saliva, a blood sample, or if their long-lived relative is deceased, a tissue sample, to the project. Then the samples are analyzed by Betterhumans and their research partners.

It may be more than being devoid of disease causing mutations that keep those over 110 in good health. Credit: Getty Images.

Supercentenarians live more healthy, disease-free lives in their autumn years than even centenarians. Their genomes are not just devoid of disease causing mutations, they must also contain actively protective genes. Previous work has been stunted however by a lack of supercentenarian DNA to work with. Betterhumans is hoping to overcome this problem.

The nonprofit says it uses a specific identification system, assigning a proprietary number to each sample, so that the subject can remain anonymous. Once a large number of samples have been processed, they’re sent to a lab for sequencing. Both proprietary and public-domain software is used. Besides sequencing, Betterhumans is comparing and contrasting supercentenarian DNA with non-supercentenarian DNA. It takes three months total from the time they take the sample to the time it’s turned into data.

2,500 differences in supercentenarian DNA have been tagged thus far, but it’s hard to discern which are significant. Extremely rare mutations might be difficult to detect using standard methods. Scanning procedures are set to look at places that are already known to harbor mutations.

A significant number of variants for supercentenarians have been found so far. Deciphering them is another matter. Credit: Getty Images.

So will we all be living to 110 in a decade or two? There’s still a contentious debate on whether or not there’s a limit to the human lifespan or if science can eventually make it limitless. But let’s say for the sake of argument that we can, should we?

The project has natural limitations. To understand all the phenotypes or combination of genes involved, tens of thousands of genomes would need to be sequenced. Yet, there are only about 150 supercentenarians worldwide. Just one in five million Americans is one. Also, some of them are hard to find. They may be living in rural areas in developing countries and did not receive a birth certificate when they were born.

Those who have a supercentenarian in their life or are one and want to contribute, contact Betterhumans and donate a sample. Contact them by phone at: (509) 987-5282, email: [email protected], or by filling out an enrollment form here.

To learn about another significant breakthrough in the quest for longevity, click here: