Be skeptical of studies designed to scare you about CTE and sports

- A recent study attempted to link chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) with early deaths among athletes, but the research had major limitations.

- Compared with contact sports, bicycling — which kills nearly 1,000 Americans each year — is far more dangerous.

- As long as everyone is properly informed, professional and amateur athletes can decide for themselves whether contact sports are worth the risk.

Whenever someone tries to make a claim that X is dangerous, like contact sports (and American football in particular), it is imperative to compare it to something else before we can make any definitive conclusions. Without context, statistics might be technically correct but very misleading. So, how do contact sports compare to an activity that society encourages: bicycling?

According to the CDC, nearly 1,000 Americans die and another 130,000 are injured each year while on bicycles. Sudden deaths are almost unheard of in contact sports, and when they do occur, the most common cause is a genetic heart defect. Thus, compared to contact sports, sudden deaths are common among bicyclists. (Additionally, a study in Great Britain found that, per mile traveled, bicyclists were about 15 times more likely to be killed than a car driver.)

Are there calls to eliminate bicycles? No. On the contrary, cities are scrambling to put in more bicycle lanes, despite the indisputable statistical fact that this is a relatively dangerous way of getting exercise or going on your daily commute. Yet, the national conversation about contact sports is headed the other direction. There even have been calls to ban American football. It is worth examining the evidence on CTE and contact sports — and injecting some reasonability into this debate.

A new study on CTE and early death

Certainly, getting hit in the head over and over and over again is not good for you. There is very good reason to believe that repetitive head injuries can result in mental health problems like depression, personality changes, and cognitive decline, all characteristic of the neurodegenerative condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). It’s a serious issue that needs a serious investigation.

But that’s not what we always get. Instead, we often get alarmist headlines like “Study finds connection between CTE and athletes who died before age 30.” The average person reading that will think, “Athletes get CTE, and then they die young. That’s scary.” Indeed, that headline is meant to scare you. But it is a pretty wild exaggeration of the research paper upon which this news article is based.

Unfortunately, this isn’t simply a case of media sensationalism; the authors of the research paper, which was published in JAMA Neurology and was much more humble in its conclusions, are providing statements to the media that aren’t supported by the data in their own paper. In a press release issued by Boston University (where the study was largely conducted), lead author Dr. Ann McKee said, “The fact that over 40% of young contact and collision sport athletes in the UNITE brain bank have CTE is remarkable — considering that studies of community brain banks show that fewer than 1% of the general population has CTE.”

The implication of her statement is clear: CTE is 40 times more common among athletes than among the general population. Therefore, contact sports are dangerous. (And given that the study used the brains of dead young athletes, the implication is even more ominous than that.) But the data does not support that insinuation.

Dissecting the study

The study has several limitations. First, the brains analyzed were not a random sample. All 152 brains were donated by family members of the deceased. This is a problem because, like those individuals who leave nasty restaurant reviews online, people are especially motivated to do something when they have a very negative experience. In this case, traumatized family members were perhaps likelier to donate their child’s brain if they had noticed something strange about their behavior. This can introduce a substantial bias into the sample. (To be fair, it’s basically impossible to get a random sample of dead brains, and the paper acknowledges this limitation.)

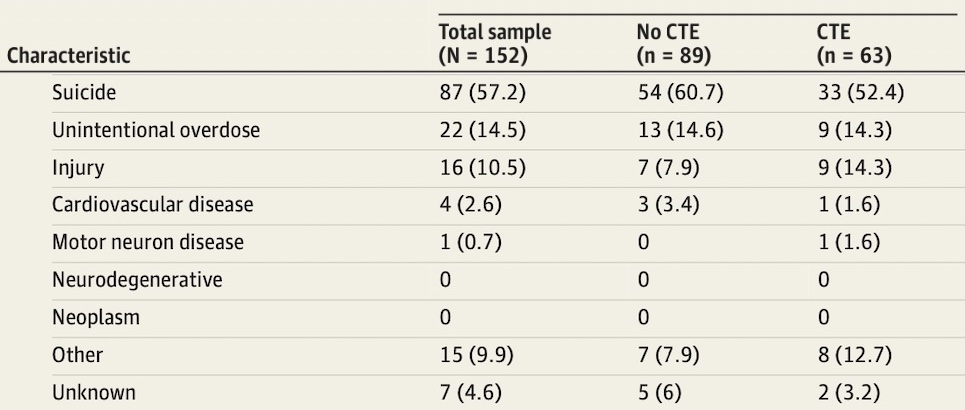

Second, the causes of death appear to be related only tangentially to CTE.

Cardiovascular disease (4 deaths) has nothing to do with CTE; 22 deaths are listed as “other” or have no known cause; and we aren’t told what the 16 injury-related deaths are. (Big Think emailed Dr. McKee for clarification and comment, but she declined our interview request.)

The only causes of death that might be related to CTE are suicide, unintentional overdose, and motor neuron disease. But as shown in the table, 52% of athletes with CTE died by suicide, while 61% of athletes without CTE died by suicide. Deaths by unintentional drug overdose were essentially identical between the two groups (14% to 15%). There was one death from motor neuron disease, but it is impossible to conclude anything from a sample size of n = 1. Therefore, based on their data, it is unclear if there is any relationship at all between CTE and early death or cause of death.

Finally, there is no definitive way to diagnose CTE while someone is alive. The symptoms listed earlier (mental health issues, personality changes, and cognitive decline) are not dispositive; the only way to know for sure if someone has CTE is to slice open their brain. Many or most people living with CTE today probably have no symptoms. So, we don’t actually know what percentage of the general population or athletes in contact sports have CTE.

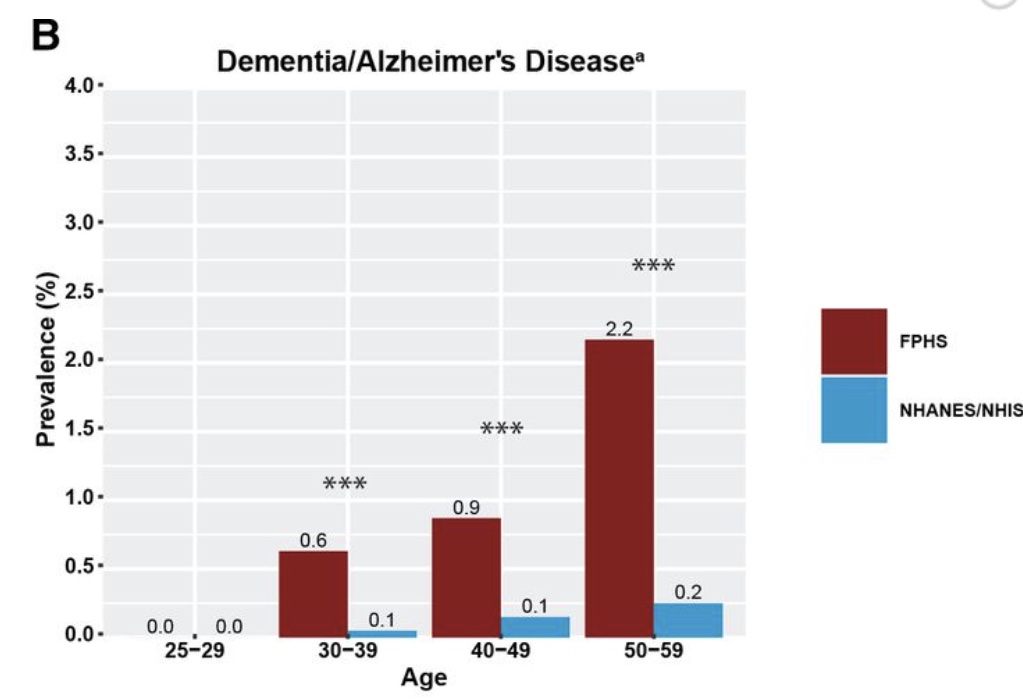

Football is risky

One of the paper’s more relevant findings was that, among the 152 brains they analyzed, football players had a higher prevalence of CTE. This is consistent with the results of a much more convincing study published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine that analyzed the health of former NFL football players. It found that, compared to the general population (shown in blue below), former NFL players (shown in red) were 6 times, 9 times, and 11 times more likely to have dementia in their 30s, 40s, and 50s, respectively. (Note that while prevalence and chance/risk/likelihood of disease aren’t the same thing, they are probably roughly equivalent in this case.)

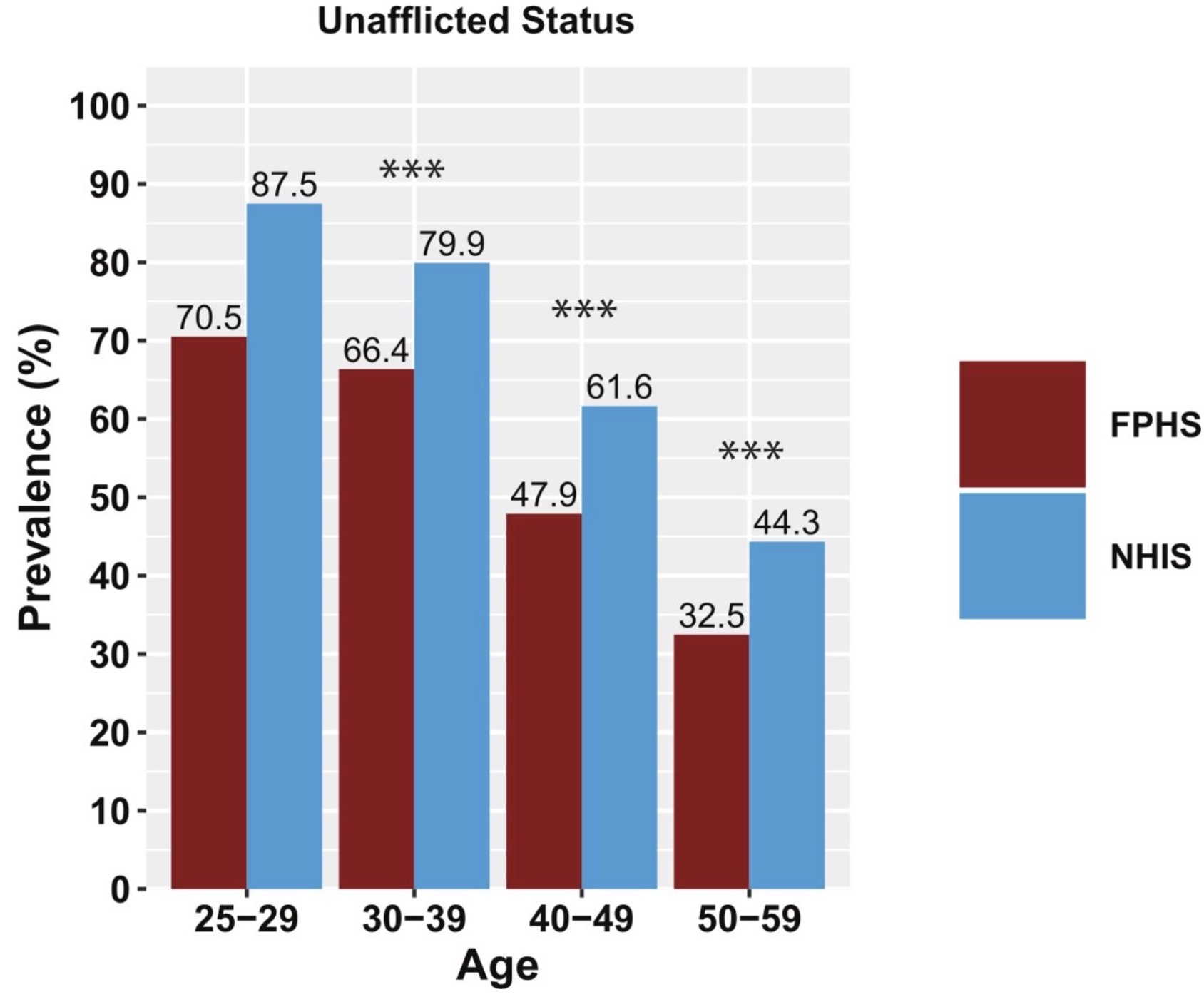

Moreover, this research showed that the healthspan (that is, the years of healthy life) was shorter among former NFL players than among the general population. The absolute difference in health status was about 12 to 15 percentage points in each decade of life. For example, the average person in their 50s has a 44% chance of being completely healthy, while the average former NFL player in his 50s has a 32% chance of being completely healthy. Overall, the data showed that NFL players have a greater risk of prematurely aging by 10 years.

Obviously, this is a concern, but it hardly justifies alarmism. Football is risky and it wears down the body. However, many NFL players are compensated handsomely and can decide for themselves if this is a risk worth taking. (The conversation is trickier when it involves high school and college players, who don’t receive that kind of compensation. But as long as everyone is properly informed of the risk, parents and kids can decide for themselves if contact sports are worth it.)

Alternatives must be offered

What conversations about risk often lack is a reasonable alternative. In this case, let’s say that we completely eliminate contact sports like football, soccer, and hockey. What is the alternative? Should everyone play basketball? We have an obesity epidemic, in large part because we aren’t getting enough exercise. The most likely outcome of scaring parents and their kids away from contact sports is to create more video game-playing couch potatoes. Society would not be better off.