How BioNTech’s “revolutionary” lung cancer vaccine actually works

The promising new treatment builds on research that went into developing COVID vaccines.

- Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide.

- A lung cancer vaccine developed by Germany-based BioNTech uses mRNA technology to train the immune system to detect and destroy cancer cells.

- Currently in trials, the vaccine aims to complement existing treatments and could help reduce recurrence in early-stage cancer.

For a substantial part of human history, people thought smoking tobacco was perfectly healthy. Native American tribes, who introduced the tobacco plant to Europeans and — by extension, the rest of the world — used it for cultural and spiritual purposes, giving little thought to its long-term effect on the human body.

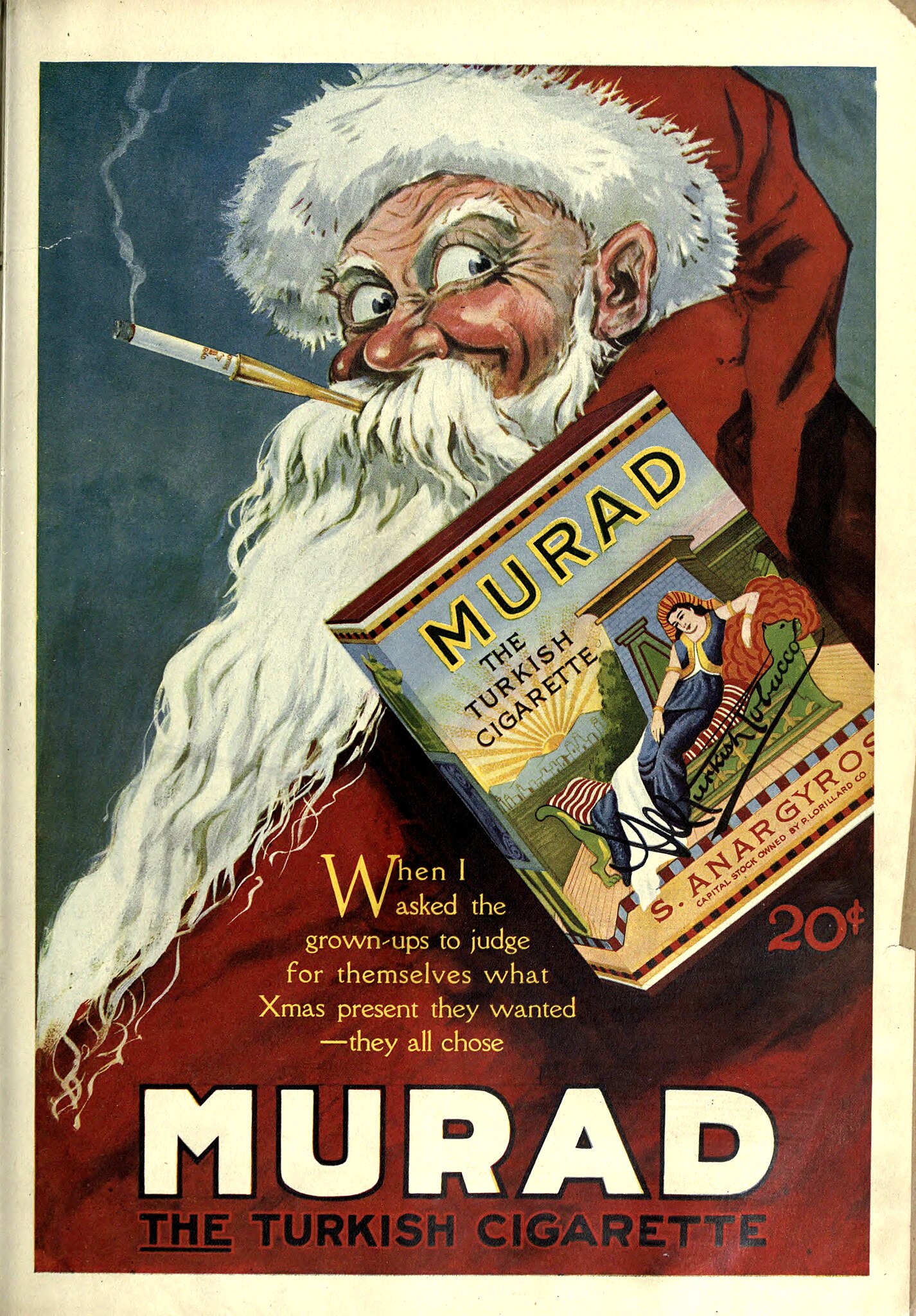

Meanwhile, vintage advertisements from the early 20th century claimed that smoking provided a variety of health benefits, from relieving stress and anxiety to helping with indigestion, weight gain, depression, and even respiratory infections. Plus, Big Tobacco frequently partnered with physicians and other health professionals to give such claims an extra air of credibility.

Interestingly, this unlikely partnership was itself a response to a growing body of research introducing the now universally known fact that smoking does – in fact – lead to serious, often life-threatening health complications, including throat, mouth, and lung cancer. Lung cancer alone killed more than 1.8 million people in 2020, making it the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide.

Over the years, government agencies and activist groups have greatly restricted Big Tobacco’s power to drive down the number of smokers, providing resources for aspiring quitters, replacing those aforementioned, Norman Rockwell-style advertisements with disconcerting pictures and health warnings, driving up cigarette prices, and limiting tobacco sales to specialized shops.

Still, the number of lung cancer deaths remains astronomically high. Fortunately, new and improved treatments for smoking-related illnesses have been making tremendous progress, with fields like nanosurgery and immunotherapy injecting hope into what is otherwise an extremely upsetting subject. But no alternative treatment option has received quite the same level of attention as German biotechnology company BioNTech’s lung cancer vaccine.

Drawing on technologies used in the creation of COVID-19 immunizations, BioNTech launched its first clinical trials involving the new vaccine in August 2024. While media outlets praised the trials for their promise and potential, most of the coverage has focused on the company’s skyrocketing valuations, leaving many to wonder how the vaccine actually works on a scientific level, why it arrived at the time that it did, and when (if ever) it will become a widely available form of treatment.

How it works

To understand how BioNTech’s lung cancer vaccine works, you first have to understand why we’d need a vaccine in the first place. While a functioning immune system can fight against plenty of nasty, potentially dangerous ailments, cancer cells — abnormal, continuously growing tissue — are, regrettably, supremely adept at slipping under the system’s radar.

That’s because, in simple terms, cancer cells aren’t external invaders but malfunctioning cells from our own body, making them harder for the immune system to recognize as a threat. More specifically, small, newly formed cancer cells often lack strong antigens — or can suppress immune responses — allowing them to evade detection. By the time they do express recognizable antigens, the tumors may have grown too large for the immune system to effectively eliminate on its own.

This insight marks the jumping-off point for immunotherapy treatment, which — unlike chemotherapy or surgery — does not target cancer cells directly, but instead helps the immune system carry out its job more effectively.

Some immunotherapies are injected directly into the veins. Others come in the form of pills or creams. BioNTech’s is a vaccine. Specifically, it’s a vaccine containing mRNA, or messenger-RNA, which can be loosely defined as a genetic blueprint for the production of proteins. In this case: proteins that improve the immune system’s ability to find and kill tumors.

“The role of mRNA is to carry protein information from the DNA in a cell’s nucleus to the cell’s cytoplasm (watery interior),” notes the National Human Genome Research Institute, “where the protein-making machinery reads the mRNA sequence and translates each three-base codon [sequences made up of the DNA molecules adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T)] into its corresponding amino acid in a growing protein chain.”

A BioNTech spokesperson tells Big Think that the vaccine “is designed to train the immune system to specifically recognize and attack cancer cells by delivering mRNA that encodes for cancer-specific antigens, prompting the immune system to target those proteins presented by tumor cells. This can help the body to detect and destroy cancer cells and potentially prevent them from returning.”

COVID lessons

BioNTech’s vaccine draws heavily from scientific advancements made during the pandemic, which led to the creation of vaccines that also use mRNA to assist the immune system in identifying a specific target. In this case: coronavirus.

Although mRNA was first discovered in 1961 (earning the researchers involved a Nobel Prize), and Penn Medicine employees Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman figured out how to use it in a vaccine as early as the 1990s, its primary application at the time — fighting infectious diseases in Africa — failed to garner sufficient funding from Western investors. Then, of course, came COVID.

BioNTech has a long history working with mRNA. During the pandemic, it co-developed the coronavirus vaccine distributed by New York-based pharmaceutical conglomerate Pfizer, Inc., discovering a mechanism capable of delivering genetic information to dendritic cells (a type of immune cell), vastly improving the vaccine’s efficacy and stability.

As clinical trials continue, BioNTech stresses that its vaccine is currently not intended to replace existing treatments for late-stage lung cancer.

“In early-stage,” the company tells Big Think, “where the immune system might be more responsive to the approach since the tumor burden is lower, BNT116 [the vaccine’s official name] could potentially be evaluated as a standalone treatment. However, it’s generally designed to complement existing treatments, such as surgery, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy, to enhance the overall effectiveness of cancer treatment and reduce the risk of recurrence.”

When and whether BioNTech’s lung cancer vaccine will become a widely available form of treatment depends on the outcome of the company’s ongoing clinical trials, which are currently taking place at 34 research sites across 7 countries — including Germany and the UK — and involve around 130 test subjects who receive 1 vaccine per week for 6 consecutive weeks, followed by one vaccine every 3 weeks for 54 weeks.

The first person to receive BioNTech’s vaccine, a 67-year-old, Polish-born analyst named Janusz Racz, credits his profession for motivating him to join the trial. “As a scientist myself,” he said in an article published by University College London Hospitals, where he is being treated, “I know that science can only advance if people agree to participate in programmes like this.”