Chronic inflammation may be a “disease of affluence”

- Research suggests that people raised in developed countries tend to have higher levels of chronic inflammation than those raised in less developed areas.

- In a recent paper, a biological anthropologist hypothesizes that this disparity may be due to upbringing: Living in overly sanitized conditions early on in our lives may be miscalibrating our immune systems, resulting in a malfunctioning inflammatory response.

- Is there a remedy for widespread chronic inflammation? Proper diet and regular exercise can help, but if Thom McDade’s hypothesis is correct, a longer-term cure is providing the immune system with reasonable adversity early on.

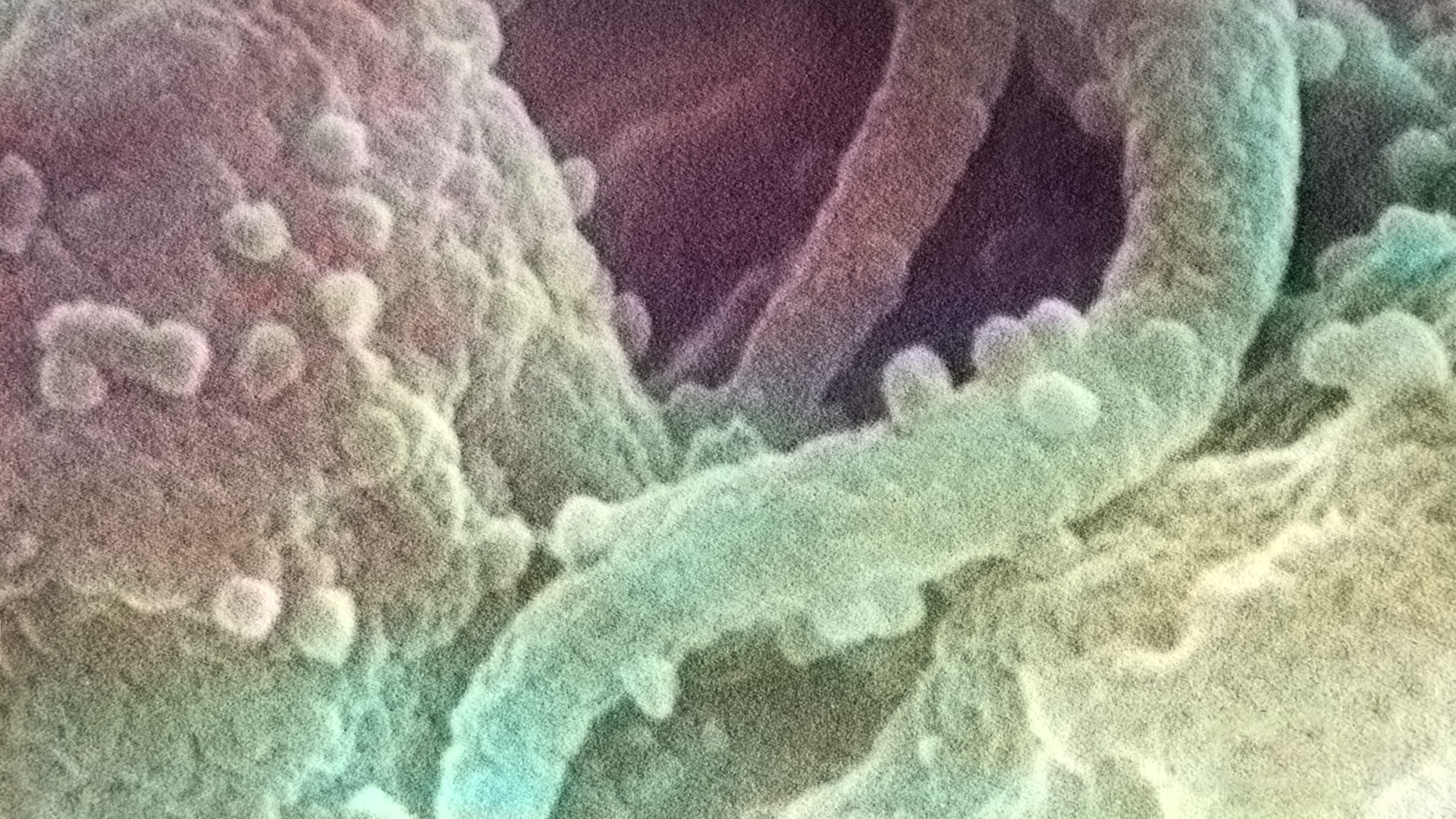

When you’re injured or sick, you should generally welcome signs of inflammation, such as redness, tenderness, heat, and swelling. These herald that the cavalry has arrived — your immune system is hard at work fighting off pathogenic invaders or beginning the healing process.

But when inflammation is omnipresent — regularly manifesting as joint pain, rash, or low-grade fever — that’s a sign that something is amiss. An essential tool of the immune system is malfunctioning: Rather than swiftly reacting to bodily harm and then dissipating when the threat has waned, inflammation is loitering like an unwelcome guest, potentially dealing unintended damage to the body and elevating the risk of heart disease and stroke.

When scientists have searched for biomarkers of chronic inflammation in individuals, they generally find them. One such marker, C-reactive protein, tends to show up in both young and elderly subjects, steadily increasing with age. This has prompted researchers to coin the concept of “inflammaging,” suggesting that rising chronic inflammation is simply a facet of getting old.

The thing is, these chronic inflammation studies have almost entirely been conducted in Western, industrialized societies, where residents tend to live sanitized, sedentary lives, with copious access to calorie-dense foods. Professor Thom McDade, a biological anthropologist at Northwestern University, says this narrow focus is skewing the scientific literature and leading to incorrect conclusions about chronic inflammation.

In a recent article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, McDade detailed research he conducted in the Philippines and Ecuador showing that chronic inflammation is relatively rare among people who don’t live Western-style lifestyles, and it is not inevitable with age.

Calibrating the immune system

So what is causing the high levels of inflammation among people raised in the West? Prior research has implicated excess body fat, but curiously, McDade didn’t find a link between body fat and levels of C-reactive protein among the Ecuadorians and Filipinos he studied.

This turned his attention to a different explanation: their upbringing. The populations he studied grew up in rural, dirty areas where they were frequently exposed to infectious diseases. He hypothesizes that this less-than-sanitary life early on effectively calibrated their immune systems, tuning their inflammatory responses to properly react to threats. These days, children in Western societies often don’t have their immune systems regularly challenged.

“Protection from potentially lethal infections is an obvious benefit and an important driver of the epidemiological transition toward increased life expectancy,” McDade noted. “But regimes of sanitation and hygiene that control lethal pathogens also reduce exposure to the harmless microbes that have been part of the human environment for millennia.”

In keeping with his hypothesis, he noted that when children grow up in rural areas in Bangladesh or Ecuador and then migrate to the US or the UK, they have lower baseline C-reactive protein as adults compared to adults who were born and raised in those countries.

“In many ways, chronic low-grade inflammation can be considered another ‘disease of affluence,’ a mismatch between our evolved biology and historically recent societal conditions that extend average life expectancies but also increase burdens of non-communicable diseases,” McDade wrote.

McDade’s idea is closely related to the widely evidenced “hygiene hypothesis,” which blames overly sanitized conditions for increasing rates of allergies and other autoimmune disorders in developed countries.

Is there a remedy for widespread chronic inflammation? Proper diet and regular exercise can help, as they do for almost any ailment. But if McDade’s hypothesis is correct, a longer-term cure is providing the immune system with reasonable adversity early on. Parents don’t have to let their kids crawl around landfills, but a little more dogs and dirt and a little less hand sanitizer and antibacterials seem reasonable.