Chemists modify hallucinogen to treat depression and addiction

Credit: David S. Soriano / Wikimedia Commons

- For decades, people have reported that the psychedelic drug ibogaine seems to rid addicts of their cravings for drugs.

- In a new study, researchers created a variant of ibogaine that’s less toxic and doesn’t cause hallucinations.

- The results showed that the variant seemed to significantly lower depression and drug relapse rates in tests on mice.

A new study suggests a modified version of the psychedelic drug ibogaine could help treat addiction and depression.

Although the ibogaine variant has yet to be tested on humans, rodents who were treated with it showed decreased symptoms of depression and significantly fewer drug relapses, especially for opioids.

What’s also encouraging is that the variant is far less toxic and hallucinogenic than ibogaine, meaning it has the potential to become a more widespread treatment than its psychedelic relative.

First, what’s ibogaine?

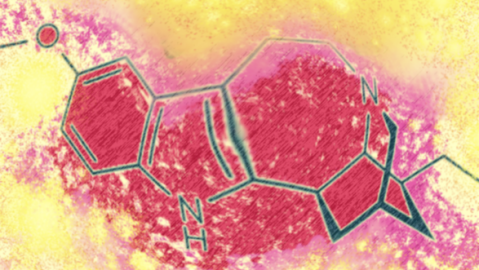

Ibogaine is a uniquely powerful psychedelic drug that produces hallucinations and other effects that can last 24 hours. It’s the active compound in the iboga plant, which has been used for medicinal and religious purposes in West Africa for centuries. The drug is central to the Bwiti spiritual discipline, practiced by Bantu peoples in Gabon.

In the 19th century, French Christian missionaries sought to rid the Bantu of their religious practices, causing some of the Bantu tribespeople to flee deep into the jungle, where they encountered Pygmies. The Pygmies showed igoba to the Bantu, who later incorporated it into Bwiti initiation rites.

Despite its religious applications, ibogaine is neurotoxic and can cause irregular heartbeat. At high doses, the substance can be lethal.

But it’s also thought to have a unique therapeutic effect: For decades, people have reported that ibogaine seems to significantly—and in some cases, completely—rid addicts of cravings for drugs.

How? One hypothesis is that psychedelics like ibogaine help the brain grow more dendritic spines, which promote communication between neurons. This strengthened communication may benefit addicts, who often show decreased synaptic connections in the prefrontal cortex.

Tabernanthe iboga bark powderCredit: Kgjerstad / Wikimedia Commons

To explore ibogaine’s potential as an addiction treatment, the researchers behind the recent study, published in the journal Nature, aimed to create safer, less toxic analogues of the drug.

The team created an ibogaine variant that, like ibogaine, had an element called a tetrahydroazepine ring, which seems to be involved in promoting the growth of dendritic spines. This variant—a compound called tabernanthalog (TBG)—was less toxic and less hallucinogenic.

Experiments on mice suggested TBG has antidepressant and anti-addiction potential.

One test showed that mice subjected to a series of stressors showed less depression symptoms after one treatment, effects similar to ketamine, another psychedelic drug. More surprising was a test on opioid addiction: TBG seemed to virtually eliminate relapses in mice who had become addicted to heroin. This anti-addictive effect lasted about two weeks.

The researchers suspect TBG might be able to treat multiple conditions simultaneously.

“We’ve been focused on treating one psychiatric disease at a time, but we know that these illnesses overlap,” David Olson, assistant professor of chemistry at UC Davis and senior author on the paper, told UC Davis News. “It’s unbelievable how little we know about them.” “It might be possible to treat multiple diseases with the same drug.”

But before drugs like TBG could be used to treat addiction or depression in humans, more research will be needed to better understand the drug, its safety and whether its therapeutic effects extend beyond rodents. Another interesting question, though not explored by the study, is whether the psychedelic properties of ibogaine possess therapeutic benefits; by removing the trip aspect, would users be missing out?

Maybe. Psychedelic experiences are mysterious and highly subjective, with some people reporting terrifying and negative trips, while others gain useful insights. Here’s one account of a positive experience posted on Erowid:

“[1 hour 20 minutes after ingestion] I am having an intense communion with a spirit in the shape of a purple-colored, brain-shaped cloud of vapor, which shows me the interconnection of myself and all things in the universe. It must sound comical to read it in words, but it was the most profound and beautiful experience in my life.”

“[7 hours after ingestion] […] something interesting has started happening in my brain. I feel as if there is a distinct second consciousness inside me, and I can carry on internal conversations with it, asking questions, receiving answers. The other consciousness seems extremely wise, I sense it is another part of me that has never been encumbered by fears or doubts […]”

To be sure, you can also find reports of ibogaine making people sick, being too powerful or not being worth the money to experiment with it at a treatment center. But regardless of the psychedelic properties, the new study adds to the renaissance of research exploring how psychedelics can help treat mental health conditions.