New AI from Harvard predicts who is most at risk of pancreatic cancer

- Pancreatic cancer has a low survival rate because people typically don’t experience any symptoms until a tumor is large or the cancer has spread to other organs.

- Screening asymptomatic people could lead to earlier detection, but the only tests for pancreatic cancer are expensive or invasive. As a result, they’re reserved for the few people doctors believe are at high risk.

- Researchers from Harvard have developed an AI that can identify which patients are most at risk of pancreatic cancer based solely on medical records.

An AI that can identify the patients most at risk of pancreatic cancer could lead to earlier detection of the deadly disease, which currently kills 88% of patients within five years of diagnosis.

The challenge: People with pancreatic cancer typically don’t experience any symptoms until a tumor is large or the cancer has spread to other organs. As a result, most aren’t diagnosed until their cancer is advanced and much harder to treat.

Screening people without symptoms for pancreatic cancer could lead to earlier detection, but the only tests for it are expensive or invasive. As a result, they’re reserved for the few people doctors believe are at high risk of pancreatic cancer, due to a family history of the disease, for example.

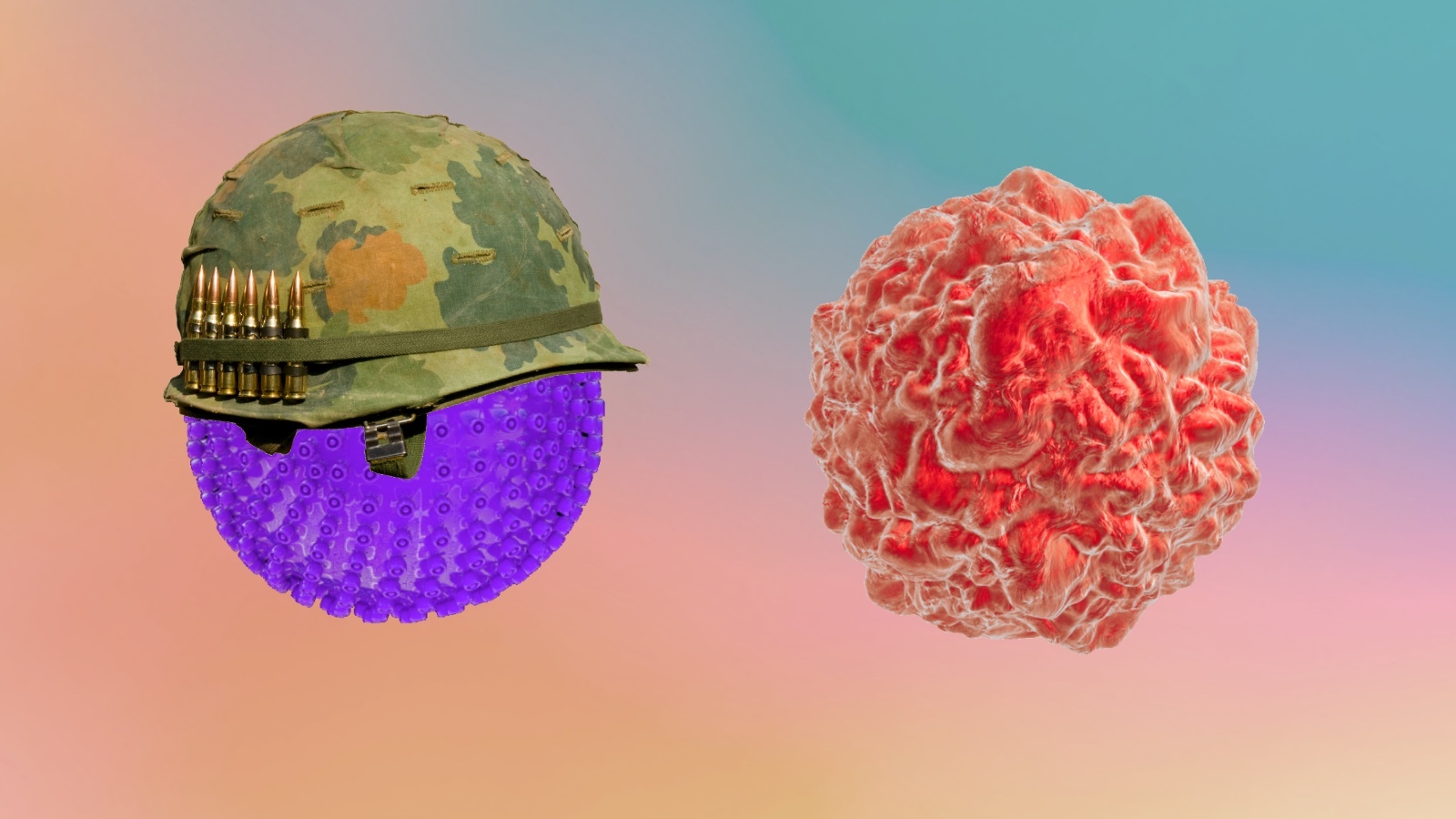

The AI looks for patterns of health problems that often precede pancreatic cancer.

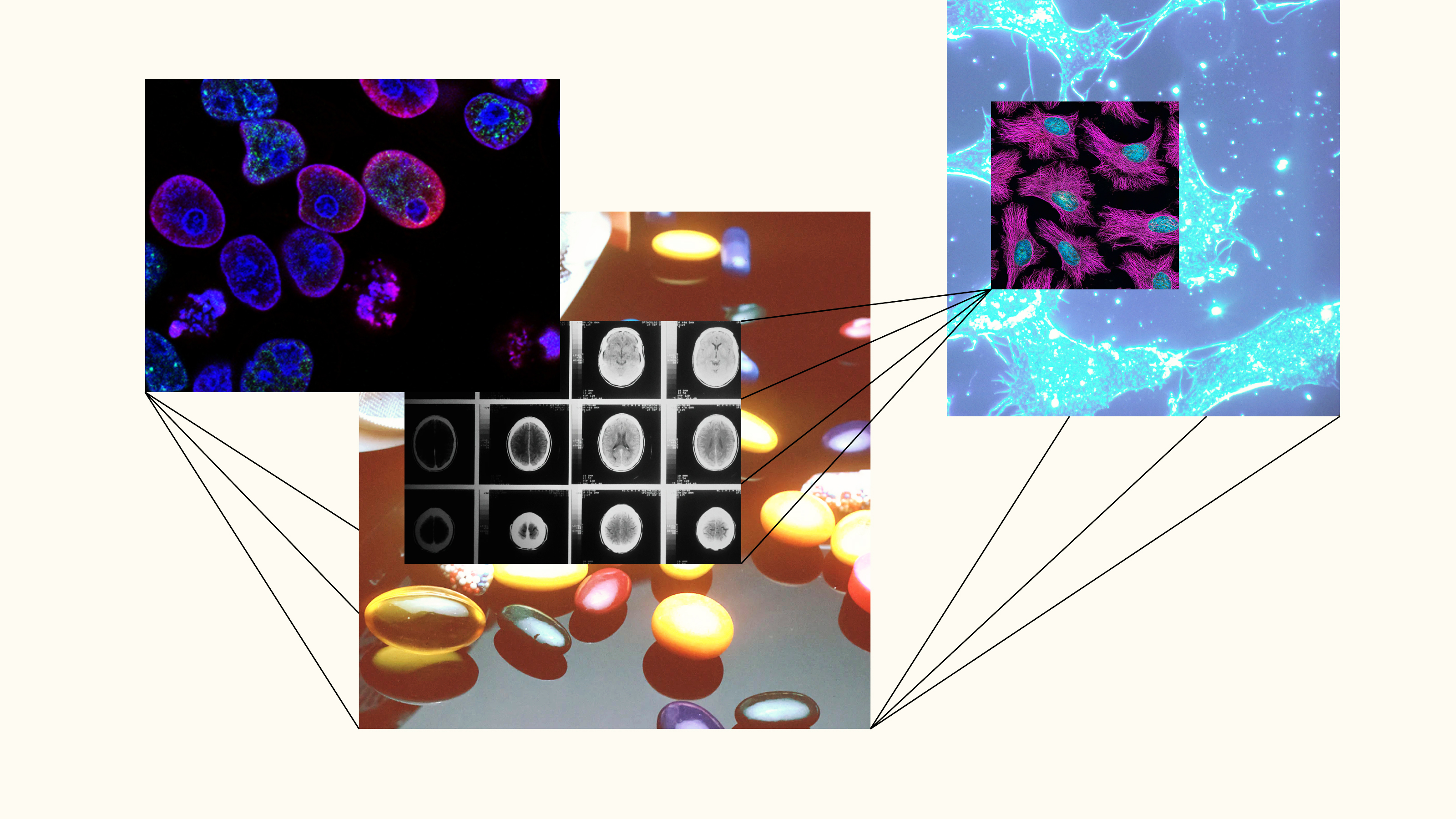

What’s new? Now, researchers at Harvard Medical School and the University of Copenhagen have developed an AI that can identify which of a healthcare system’s patients are most at risk of pancreatic cancer based solely on medical records, flagging them for screening.

“An AI tool that can zero in on those at highest risk for pancreatic cancer who stand to benefit most from further tests could go a long way toward improving clinical decision-making,” said Chris Sander, the study’s co-senior investigator.

How it works: The researchers trained and tested their AI using the health records of 6.2 million people in Denmark. The records spanned 41 years and included about 24,000 people with a pancreatic cancer diagnosis.

The AI can identify the patients within a larger population at highest relative risk of the disease.

From the training data, the AI learned to identify patterns of health problems — including gallstones, anemia, and type 2 diabetes — that people with pancreatic cancer often experience in certain sequences prior to their cancer diagnosis.

“Cancer gradually develops in the human body, often over many years and fairly slowly, until the disease takes hold,” Sander told the Register. “The AI system attempts to learn from signs in the human body that may relate to such gradual changes.”

These issues are all quite common, of course, and pancreatic cancer is very rare, so by themselves they don’t indicate much about an individual’s risk. But the AI seems to be able to pick up on patterns in health events that aren’t easily noticeable by skimming a patient history.

The results: While the AI can’t just look at one person’s record and say they have an absolute X% chance of developing pancreatic cancer in the next year, it can identify the patients within a larger population at highest relative risk of the disease, according to the team’s study.

For every 1,000 patients over the age of 50 that the AI flags, 320 will go on to develop pancreatic cancer.

In an interview with CBS News, Sander described how he envisions this ability being put to use in the field in the future.

“Every healthcare system with a million patients would run the AI software that we’ve now developed, and to be improved in the future, routinely and at low cost, for the million patients,” he said. “Then, you nominate 1,000 patients at highest risk to do screening.”

Based on the team’s study, for every 1,000 patients over the age of 50 that the AI actually flags, 320 will go on to develop pancreatic cancer. Of those 320, at least 70 likely wouldn’t have been deemed at high risk of pancreatic cancer based on any other available data.

The cold water: As part of their study, the researchers also tested their AI on nearly 3 million records from the US Veterans Health Administration. Those records spanned 21 years and included about 3,900 pancreatic cancer patients.

The AI wasn’t as accurate at identifying people at high risk of pancreatic cancer in this other dataset — according to the researchers, this may have been due to some combination of the US dataset covering a shorter period of time and inherent differences between the two populations.

“There is a clear need for better screening, more targeted testing, and earlier diagnosis.”

CHRIS SANDER

When they retrained the AI using the US data and then tested it, its accuracy improved. This suggests that the accuracy of the system depends on it being trained on robust local data prior to use as a screening tool, which could be a hurdle in some places.

“AI needs a lot of data to train,” said Sander. “Access in different locations is not straightforward, as medical records are and should be confidential. So local approval and data security is essential.”

Looking ahead: The researchers are still working to improve the accuracy of their AI, and in his interview with CBS, Sander noted that it will take “a few years” before the system could be put into practice. Still, he’s optimistic that it could revolutionize how pancreatic cancer is detected.

“[T]here is a clear need for better screening, more targeted testing, and earlier diagnosis, and this where the AI-based approach comes in as the first critical step in this continuum,” said Sander.

This article was originally published by our sister site, Freethink.