Are we psychologically prepared for the coronavirus outbreak?

Don Arnold / Getty

- The novel coronavirus has spread to all continents except Antarctica, and it’s infected more than 90,000 people as of early March.

- In China, mental health officials are trying to keep up with thousands of service requests from doctors and civilians facing fear, anxiety and exhaustion.

- It’s unclear how Americans will react if the outbreak intensifies.

Scientists have a decent understanding of how the novel coronavirus affects the body. But what’s less clear is how the outbreak — its death toll, what governments do to control it, etc. — will affect peoples’ psyche.

The situation in China provides clues: For weeks, millions of people across dozens of cities have been living under lockdown conditions, with many unable to travel, go out in public, or in some cases, leave their housing complex. Many have been isolated in mandatory quarantines. China’s President Xi Jinping told citizens: “Staying indoors is your contribution to the Party and the Country.”

But for people in Wuhan, the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak, these containment measures seem to be taking a psychological toll. Psychiatrists, psychologists, and counselors have been responding to a “surge” of service requests from doctors and civilians in the city, most of whom are dealing with panic, fear of infection, or financial stress, according to the Wall Street Journal.

How will Amercians respond, psychologically, if the outbreak intensifies? It’s a sobering question to consider, especially in light of estimates that 40 to 70 percent of the world’s population might become infected. In other words, we might soon enter a scenario where most of us know someone who dies from coronavirus, as The New York Times reported last week.

So, when gauging how Americans will react psychologically, it’s worth looking at how the Chinese are responding, and then factoring in cultural and political differences between Americans and the Chinese. For example: Americans might be more psychologically sensitive to the outbreak and its political ramifications, considering:

- The Chinese are, presumably, more experienced with viral outbreaks; they suffered the brunt of the 2002 SARS epidemic.

- The Chinese are also more accustomed to the government exercising top-down control; Americans would likely respond more disagreeably to being told they can’t book a cross-country flight.

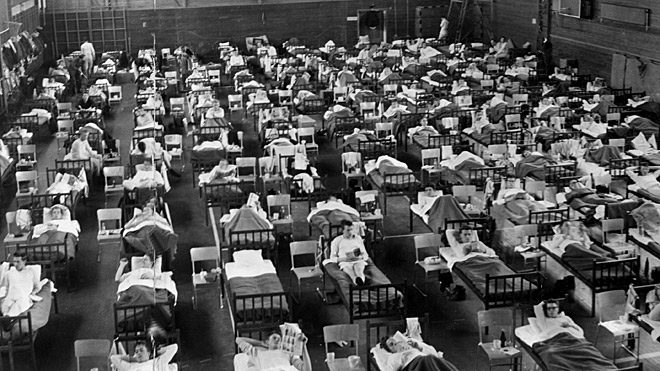

However, it wouldn’t be the first time the U.S. government compromised citizens’ individual liberties to control the outbreak of a contagious disease. In response to the 1918 Spanish Flu, for example, officials in some U.S. states banned public gatherings, forcibly isolated and quarantined the ill, and closed public schools for weeks at a time. This was the last time the government exercised large-scale quarantine and isolation measures.

In recent weeks, Americans have undergone mandatory quarantine at the nation’s borders, where the federal government’s protective powers are most clearly defined. On March 3, more than 100 Americans who had been passengers aboard a Diamond Princess cruise ship were released after spending two weeks in quarantine. Americans who recently returned home from China have also had to undergo quarantine.

Although the federal government is within its power to isolate and quarantine at-risk citizens, some civil rights activists say these measures violate individual liberty.

“Quarantining somebody is an extraordinary deprivation of their liberties,” American Civil Liberties Union senior policy analyst Jay Stanley told CNBC. “There’s a burden on the government to determine that it’s really using the least restrictive alternative.”

Coronavirus illustration

Courtesy CDC/Alissa Eckert

Beyond political implications, quarantining people may yield negative psychological effects. In a recent episode of the American Psychological Association’s “Speaking Psychology” podcast, host Kaitlin Luna cited research on people who were quarantined during the SARS epidemic.

“They found that many had psychological distress including post-traumatic stress disorder and depression,” she said. They found that the longer someone was quarantined, the higher likelihood that he or she would experience PTSD symptoms. Obviously, this shows that being isolated from others can bring up a host of negative feelings.”

But what about the millions of Americans who will never be quarantined or become infected? How will they respond psychologically? The advice from most health professionals seems to be: start preparing yourself.

“The most important recommendation is don’t panic, but prepare,” Dr. Rebecca Katz, director of the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University, told Vox. “We’re not going into a crazy movie situation where the world is on fire, but we may be going into a situation where there are people walking around who are sick.”

The ‘adjustment reaction’

Part of mentally preparing yourself involves understanding what some crisis communicators and psychiatrists call the “adjustment reaction.” This phenomenon describes how people typically react to a new and potentially serious risk, like coronavirus. For example, people tend to: pause, become over-vigilant, personalize the risk, and take extra precautions.

The adjustment reaction isn’t necessarily a negative or naive response to crisis. Rather, it seems to help people cope, and to prevent overreactions down the road.

“The ‘adjustment reaction‘ is a step that is hard to skip on the way to the new normal,” risk communications experts Jody Lanard and Peter Sandman wrote in a blog post about coronavirus. “Going through it before a crisis is full-blown is more conducive to resilience, coping, and rational response than going through it mid-crisis.”