Who’s Winning the Culture War? What the Numbers Suggest

I hear quite often enough that my values (liberal if not worse, feminist, tolerant of same-sex marriage) are responsible for American marriage decay.

This baffles me anecdotally, as I canvass my small corner of the universe. I’m 45 and I’ve been married 14 years. I’ve never been divorced. I haven’t been a single mother, a “welfare queen” or taken a thing from “The Government.” I never went to a swing party, or swung, or swanged, or got wife-swapped or raved or moshed or orgied, or woke up and had no clue what bed or city I was in. All these bogeymen of the liberal lifestyle have eluded me.

My husband and I are nothing if not persistent, and hard workers, even at moments when one or both of us would prefer to cut and run to Tahiti. We raise our child, pay taxes (and how), obey speed limits (okay, more or less), and work our butts off.

And we’re not exceptional. That’s key. We’re like our feminist-ish, liberal-ish, professional and creative class peers. A few of them are divorced. Not that many, though, and they’re not judged harshly for it.

Me and my “elk,” as an undergraduate once memorably misspoke, seem to be succeeding in marriage. We might not always be ecstatic—read my book, coming out in paperback soon—but we try to solve problems.

The numbers back up my anecdotal view. Now that the dust’s settled on the social tumult of the early 1970s, an unprecedented divorce and marriage gap has developed. The professional and affluent classes get married and stay married more successfully than lower income, working-class and poor Americans, who are falling away from the institution. Several researchers and commentators have described this, worriedly.

Additionally, iconic liberal states have lower divorce rates than iconic Bible Belt states. Massachusetts has the lowest divorce rate in the country, along with deep blue Washington, DC, New York, Maryland, as well as New Jersey and the blue-ish Illinois, also in the lower 10, along with swing states such as Pennsylvania. The 10 states with the highest rates include Arkansas, Alabama, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Idaho, Wyoming, and Nevada (home of the quickie divorce), as well as swing state Florida, mixed state West Virginia, and one liberal state—Maine.

We’re told that tolerance for same-sex marriage undermines marriage. Yet 60% of the 10 states with the lowest 2009 divorce rates have approved same-sex marriage or civil unions. Conversely, 90% of the 10 states with the highest divorce rates—all but Maine–explicitly ban same-sex marriage, and/or define marriage explicitly as “between a man and a woman.”

On the surface, it looks like bad news for social conservatives. Liberal enclaves seem to be winning the culture war.

But is that really the case? Is there a relationship between being a liberal values state and a lower divorce rate, and vice versa?

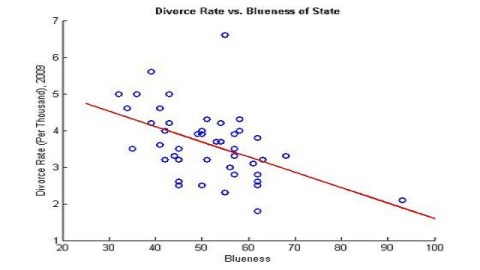

Let’s explore this. I’mnot an expert. I don’t do quantitative research. But my dear husband does have Matlab, and the wherewithal to do some basic regressions.

First I took available (four states didn’t report) state divorce rates for 2009.

Then I gathered some indicators of values from roughly the same time. My first indicator is the percentage in each state that voted for Obama in 2008, a measure of how “blue”/liberal the state is.

My second indicator is from the Pew Research Center’s Religious Landscape Survey (2007). I use “there is only one true way to interpret the teachings of my religion,” as a measure of fundamentalism.

Another Pew question, “religion is very important in my life” is used as a (third) indicator of religiosity (but not necessarily fundamentalism).

A final indicator—each state’s laws on same sex marriage, four levels ranging from “approves same-sex marriage” to “bans same-sex marriage”—measures its friendliness to same-sex marriage.

Here’s what I found: The strongest relationship (correlation 0.49 with a p-value 0.08) is between low divorce rates and the liberalism of the state, according to 2008 election results. The more liberal the state, the more likely it is to have a lower divorce rate.

I found a relationship (correlation 0.49 with a p-value 0.07) between same-sex marriage approval and lower divorce rates. However, this variable is almost binary, and might benefit from a better method of testing.

Another relationship (correlation 0.25 with a p-value 0.33) is between high divorce rates and fundamentalist views. The more fundamentalist the state, the more likely it has a higher divorce rate.

I found no relationship between divorce rates and “religion is very important in my life.” This indicator doesn’t relate to a state’s divorce rate one way or another.

Of course, a “correlation” doesn’t prove a “causal” relationship. Some elements appear together frequently, but aren’t related in the sense that one variable affects the other in statistically significant ways. They’re spurious correlations.

So we can’t jump to the conclusion that states fail at marriage partly because of their conservative family values, their non-liberal attitudes, and their intolerance to same-sex marriage. It’s tempting to do just that—since this is essentially what politicians have said about liberals for some time now.

I’m not a social scientist, so I can’t design, or envision, the research that might determine if there are, indeed, deeper relationships between values and divorce rates. I mean a more rigorous quantitative investigation, as opposed to many existing—and valuable—qualitative works, or those based on literature review.

I’m not sure that such research would be possible within statistical parameters. Some of the more advanced techniques might be able to tease out the influence of community-level variables, such as values, on individual behaviors, such as divorce (Hierarchical Linear Modeling, perhaps?).

But, what I wish that I could learn from future research, based on these preliminary numbers, is: What do values have to do with marriage outcomes within communities?

It’s an important question, because a formative political rhetoric for decades—and the whole premise of the culture war—has posited that liberal values have weakened marriage.

This political rhetoric assumes two things, both of which our regressions call into question: First, it assumes that values are relevant to marital outcomes. Second, it assumes that conservative family values support marriage, while liberal values don’t.

A null hypothesis would be that there is nothing–no meaningful relationship between values and divorce rates. And that constitutes bad news for the cultural warrior because it calls into question why they’re waging a culture war to defend marriage, when values aren’t the strongest drivers of divorce (perhaps income, poverty, and education are stronger drivers).

In contrast, the hypothesis would be that values do matter in divorce rates, in some measurable although not exclusive way. But, if that hypothesis were supported by future research, then it also would constitute bad news for social conservatives because state-by-state data suggest that liberal values are more marriage-supportive.

Sounds like heads I win, tails you lose. But I await an enterprising Ph.D. student to find out.