This week, and for the second time in history, a probe built by humans left the confines of the solar system.

The first to do so was the Voyager 1 spacecraft on September 2013, when it climbed out of the sun’s influence into the depths of interstellar space. NASA launched Voyager 1 in September 1977, when Jimmy Carter was President and I had just finished high school.

Credit: NASA

A month before Voyager 1, NASA launched its companion explorer, Voyager 2. It is the only spacecraft to have visited all four of the gas giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) and, in doing so, discovered their ring structures (we only knew about Saturn), 16 new moons, the cracks on Europa’s icy surface, and Neptune’s mysterious Great Dark Spot, similar to Jupiter’s Great Red Spot.

The cracks in Europa’s surface, by the way, may reveal the properties of the oceans that exist underneath it, inspiring NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, scheduled to launch in the mid 2020s. That mission will assess the possibility of life on Europa, one of Jupiter’s 79 moons.

Contrary to its twin, Voyager 2 still has operational instruments that will allow scientists to study the details of cosmic radiation beyond the sun’s influence. The era of direct interstellar travel and research, up to now the exclusive province of science fiction, has truly begun.

If an alien civilization had been observing Earth for prolonged periods of time, it would identify a new period in its history, starting in the late 1950s, where objects started to pop out of its surface aimed toward outer space. The two Voyager missions are the overachievers, carrying the first signs of human presence toward other stars and the worlds that orbit them.

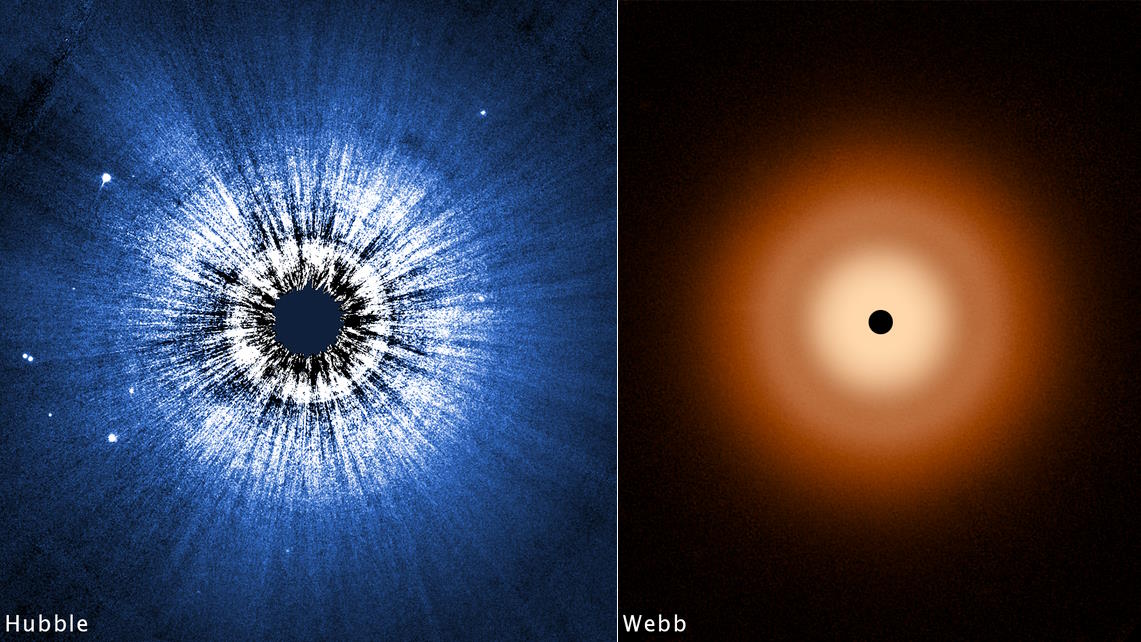

The sun, like any other star, pours huge quantities of electrically-charged particles into space, most of them electrons and protons. This solar wind, as it is called, is confined to a huge bubble known as the heliosphere. The outer edge of the bubble, the heliopause, marks the transition region beyond which the sun’s influence in the interstellar medium becomes negligible. On December 10, Voyager 2 crossed this boundary, roughly 100 times farther from the sun than we are. Even light takes some 14 hours to travel from there to here.

This remarkable technical feat is also a metaphor for science and for the human spirit. As a human creation, science represents our effort to keep on pushing the limits of knowledge. With each discovery, we learn a bit more about the world and how we fit in.

A heroic enterprise

There is something heroic in this enterprise, which has both a practical value—as scientific discoveries are used in the most diverse ways—and a more mythic dimension, as we search to answer questions as old as our existence in this planet: questions of origins, of endings, of place, and of meaning. We push boundaries so that we can learn more about who we are as a species and as individuals.

As T. S. Eliot wrote, “Only those who risk going too far can possibly find out how far one can go.” It is hard to think of a more apt description of our effort to understand the cosmos scientifically.

This is how science moves, no doubt. But it is also how I try to live my life. It is a cry against conformism, against the sameness of everyday routine. In science, the new is imperative: we need to invent a little bit more of the world every day, given that we don’t know what’s out there beyond what we know.

Of course, scientists don’t have the same freedom of a painter or a composer, given that we are bound to describe the world as is—or at least as we perceive it through our senses and the tools we use to augment them. We want to describe Nature, figure out how it works. But Nature always has the last word, even if it often forces us to toss away ideas that we think beautiful.

Greetings from Earth’s children

It is among the stars out there, in the planets and moons surrounding them, that other beings could exist, perhaps even thinking ones. Both Voyagers carry a gold-plated disk filled with sounds and images of our planet, our animals, and our culture, including a greeting read by a child: “Hello from the children of planet Earth.” The disk was Carl Sagan’s idea, who wanted to announce to our potentials neighbors that they are not alone in space.

Although the chances of an alien civilization finding the tiny probe are extremely remote at best (it’s more than 50 thousand years until it reaches the nearest star system), the gesture was essentially symbolic.

It reflects our hope that we are not alone in the cosmos, that other thinking beings do exist, preferably lovers of life and creativity, that have found a way to live together, preserving their resources and the planet that harbors them.

Watch NASA’s video about Voyager 2 going interstellar:

The post Voyager 2 Goes Interstellar appeared first on ORBITER.