Why the 4th Gravitational Wave Is a “New Window on the Universe”

The twin Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) is a collaborative effort. It’s basically a group of scientists who use specialized equipment to study gravitational waves. There are currently two such observatories in the US, one in Hanford, Washington and the other in Livingston, Louisiana. They use an interferometer, or a laser-based instrument, to detect even the minutest ripples in space-time as it relates to gravitational waves. The instrument is so delicate, it can pick up distortions one proton in width.

LIGO observatories are owned by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and are run by scientists at NASA, MIT, and Caltech. The Europeans now have their own gravitational observatory, known as Virgo, based in Italy. The two collaboratives recently started working together, and they’ve just made an announcement unveiling new results, a noteworthy milestone in gravitational astronomy.

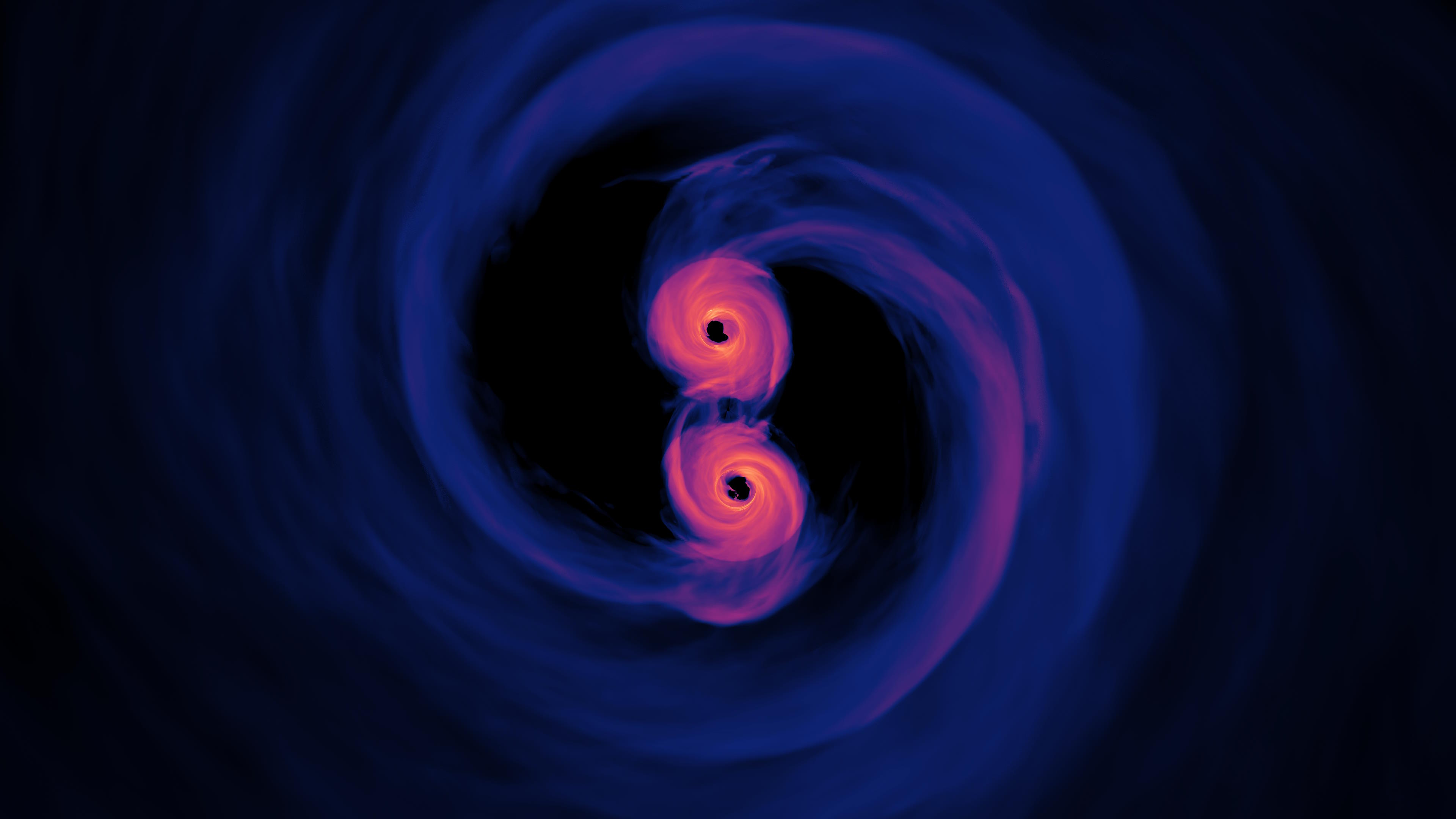

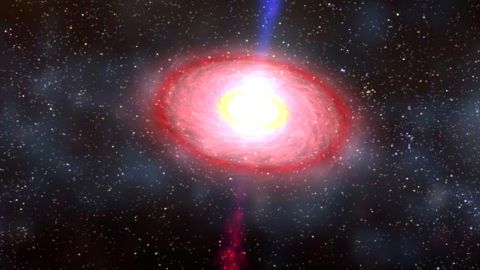

Researchers announced what they called a “new window on the universe,” at the G7 Ministerial Meeting on Science, taking place Sept. 27-28. Back on August 14, Virgo for the first time detected a gravitational wave, made by a binary black hole system. The two LIGO locations picked it up just after. The wave was created when two black holes collided and merged. All three locations registered the resulting gravitational wave.

This was the first time in history such a wave was detected on two different continents. This is more than just a scientific second opinion, it gets us closer to a 3D picture of what Einstein’s gravitational waves actually look like. The twin LIGO detectors in the United States mean scientists can detect gravitational waves, but only on one plane. The Virgo detection literally adds a new dimension to the breakthrough discovery of gravitational waves in 2015 (which is a hot favorite to win the Physics Nobel Prize this year). Professor Andreas Freise, a LIGO project scientist at the University of Birmingham, puts it like this: “It’s like if I give you just one slice of apple, you can’t guess what the fruit looks like.” The third detector also means scientists can triangulate the source of the wave to identify exactly where in the universe the signal originated.

National Science Foundation director France Córdova spoke at the press conference. She said, “This is an exciting milestone in the growing international scientific effort to unlock the extraordinary mysteries of our universe.”

See a video depicting the recorded black hole merger here:

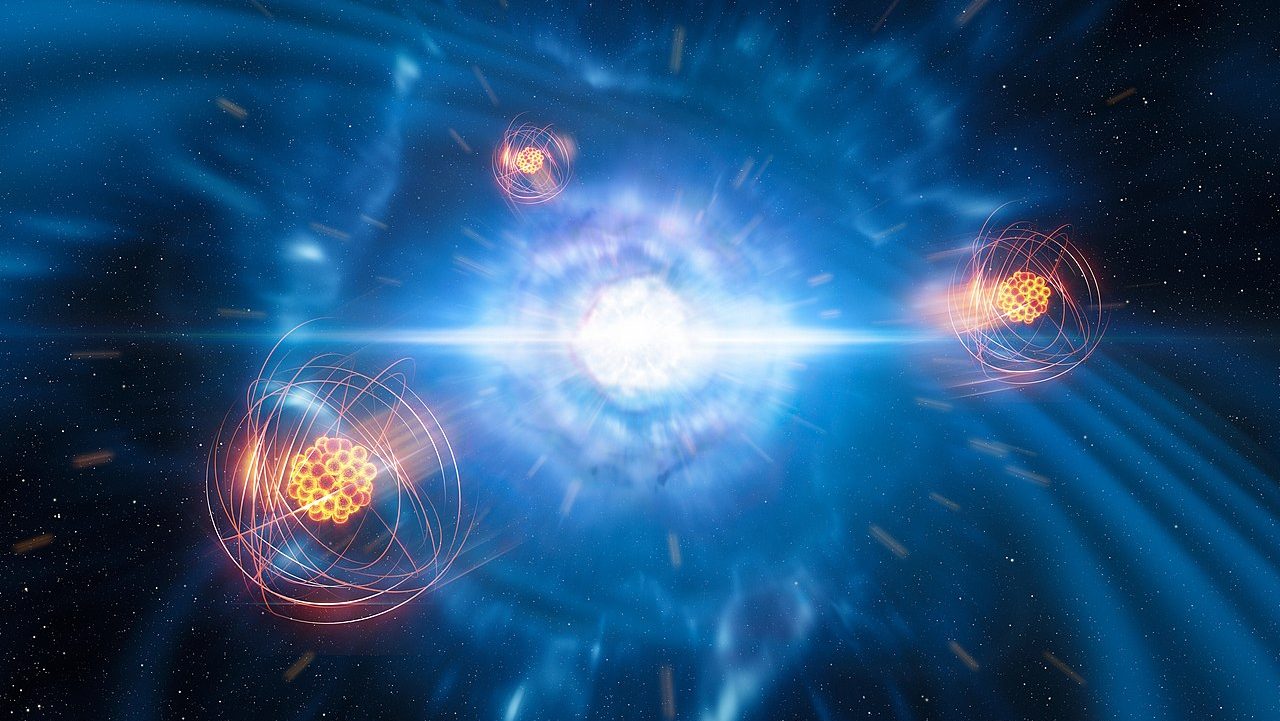

Gravitational waves were first predicted by Einstein’s general theory of relativity. LIGO’s recording of a black hole collision several months ago confirmed this famous physicists suppositions, first hypothesized in 1916. You can hear a recording of that collision. The most recently detected gravitational waves came from a location 1.8 billion light years away. These were two enormous black holes, the first 31 and the second 25 times the mass of our sun. The resulting black hole was 53 times our sun’s mass.

With three detection locations, scientists can better gauge the distance of the origin of these ripples in space-time. University of Texas astrophysicist J. Craig Wheeler perked the ears of some space heads back in August when he tweeted, “New LIGO. Source with optical counterpart. Blow your sox off!” The optical counterpart he mentioned wasn’t elaborated on until now. Scientists believe they may be able to detect other particles emanating from black hole collisions. But some space geeks took it to mean that LIGO and Virgo had detected the merger of a neutron star.

Aerial view of the Virgo detector. The Virgo collaboration/CCO 1.0

Still, what was announced is no less groundbreaking, according to Georgia Tech professor Laura Cadonati. She’s the deputy spokesperson for LIGO. “This increased precision will allow the entire astrophysical community to eventually make even more exciting discoveries,” she said, “including multi-messenger observations.” With these detectors, astronomers may also be able to find and study light, x-rays, neutrinos, and other subatomic particles emanating from cosmic events.

LIGO spokesman David Shoemaker, who is also of MIT, said, “This is just the beginning of observations with the network enabled by Virgo and LIGO working together.” He added, “With the next observing run planned for fall 2018, we can expect such detections weekly or even more often.”

More gravitational observatories are in the works in other locations, including one for New Delhi. With an international network, researchers believe they can gain better information, further test Einstein’s theory, and get more accurate location information for black hole and neutron star mergers, among other significant cosmic phenomenon.

Caltech’s David H. Reitze is the executive director of the LIGO Laboratory. He said, “We have taken one step further into the gravitational-wave cosmos. Virgo brings a powerful new capability to detect and better locate gravitational-wave sources, one that will undoubtedly lead to exciting and unanticipated results in the future.”

See the press conference for yourself here: