Scientists blow away sticky moon dust with electrons

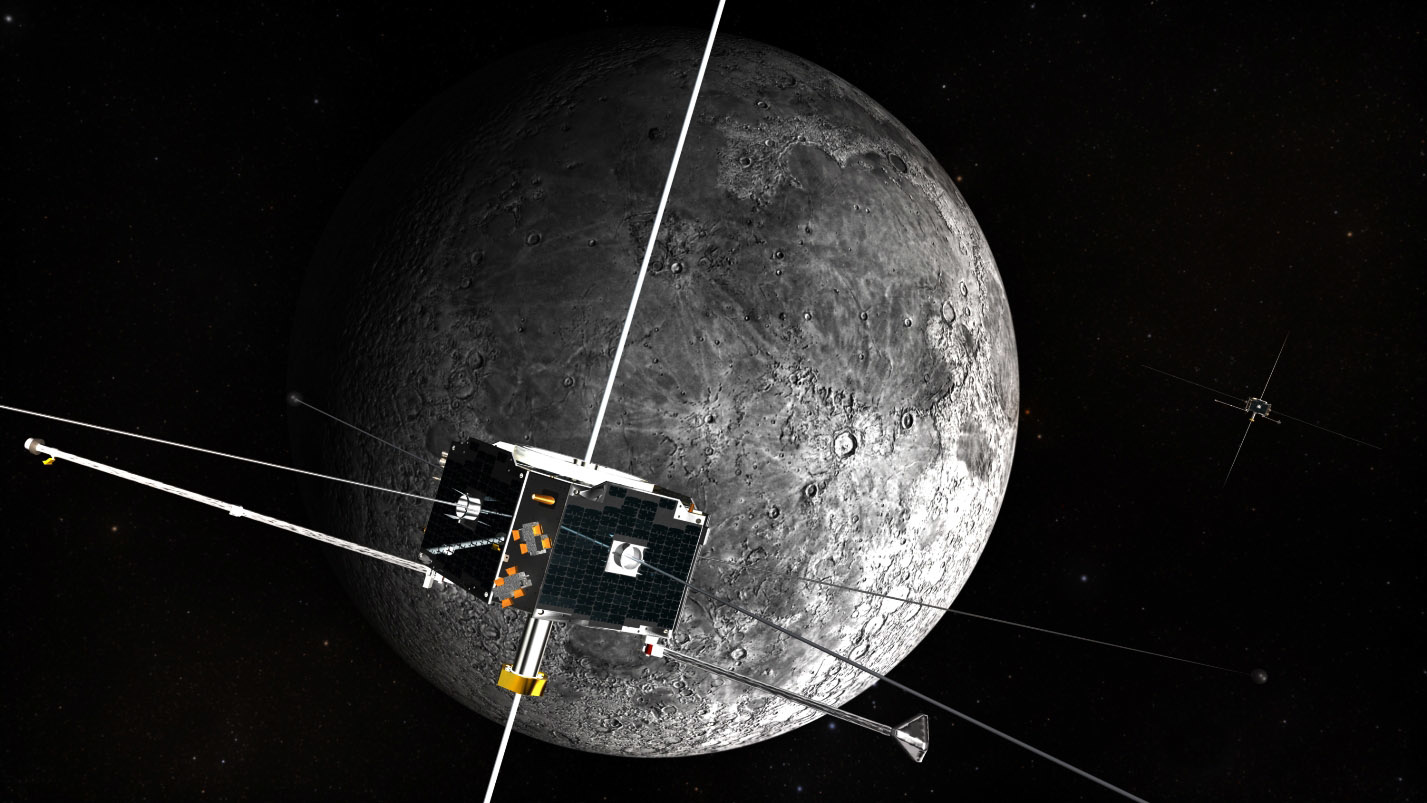

Credit: NASA

Astronaut Harrison “Jack” Schmitt, who said it smelled like “spent gunpowder” and developed an allergy to the stuff, was no fan of the moon’s peculiar brand of dust. Nor were any of his Apollo-era colleagues fond of the regolith that got kicked up from the lunar surface whenever they walked or drove around. The dust got into, and stuck to, everything.

“It’s really annoying,” says Xu Wang of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at Colorado University Boulder, speaking to CU Boulder Today. “Lunar dust sticks to all kinds of surfaces — spacesuits, solar panels, helmets — and it can damage equipment.”

The CU Boulder researchers have been working on a means of overcoming this little-known technical obstacle to moon exploration. Their research was recently published in the journal Acta Astronautica, and it involves a lunar dustbuster that disperses sticky moon dust with beams of electrons.

Microscopic view of man-made “moon dust”Credit: IMPACT lab/CU Boulder

Lunar dust is not much like the stuff settling on the surfaces of your home. For one thing, Wang reports, “Lunar dust is very jagged and abrasive, like broken shards of glass.”

The reason that it’s so stubbornly sticky is that it carries an electric charge not unlike that of a sock you’ve just removed from the dryer. The charge results from being continually exposed to the Sun’s radiation as the dust sits on the lunar surface unprotected by an atmosphere like ours. The moon does have very thin atmosphere that contains odd gases such as sodium and potassium, says NASA, but it isn’t thick enough to afford much protection from radiation.

Jumping motes of moon dustyoutu.be

The researchers explored the idea of shooting a beam of electrons at lunar dust to fill the spaces between its particles with negative charges that could push the particles further apart, away from each other and also off a surface to which they might be adhering. Says Wang, “The charges become so large that they repel each other, and then dust ejects off of the surface.”

To test their concept, the researchers acquired lunar regolith stimulant from NASA, a substance formulated on Earth that’s designed to replicate lunar dust. They placed objects of various materials that had been coated with the stuff in a vacuum chamber and fired electron beams at them. (The video above shows the dust’s response.)

Speaking of the behavior of the electron-blasted dust on a number of tested surfaces, including spacesuit fabric and glass, “It literally jumps off,” says lead author Benjamin Farr. However, the finest-grained regolith, the kind that gets stuck in brushes, remained unperturbed by the electrons. Overall, the electrons cleaned off about 75 percent to 85 percent of the dust. “It worked pretty well, but not well enough that we’re done,” says Farr. Looking forward, the team is exploring ways in which the electron beam’s cleaning power can be increased.

This is not the first attempt at using electrons to clean up lunar dust. For example, NASA has explored using nanotube electrode networks in spacesuits to keep dust off. To keep regolith off other materials, NASA is also considered combining charge-dissipating indium tin oxide with paint that could then be applied to otherwise dust-collecting surfaces.

The CU Boulder team anticipates one day hanging up a spacesuit in a room or compartment where it can be bombarded with electrons for cleaning. Even more convenient would be facilities where “You could just walk into an electron beam shower to remove fine dust,” says study coauthor Mihály Horányi of CU Boulder’s Department of Physics.