Scientists grow extremophile microbes on rocks from Mars

Credit: Milojevic et al.

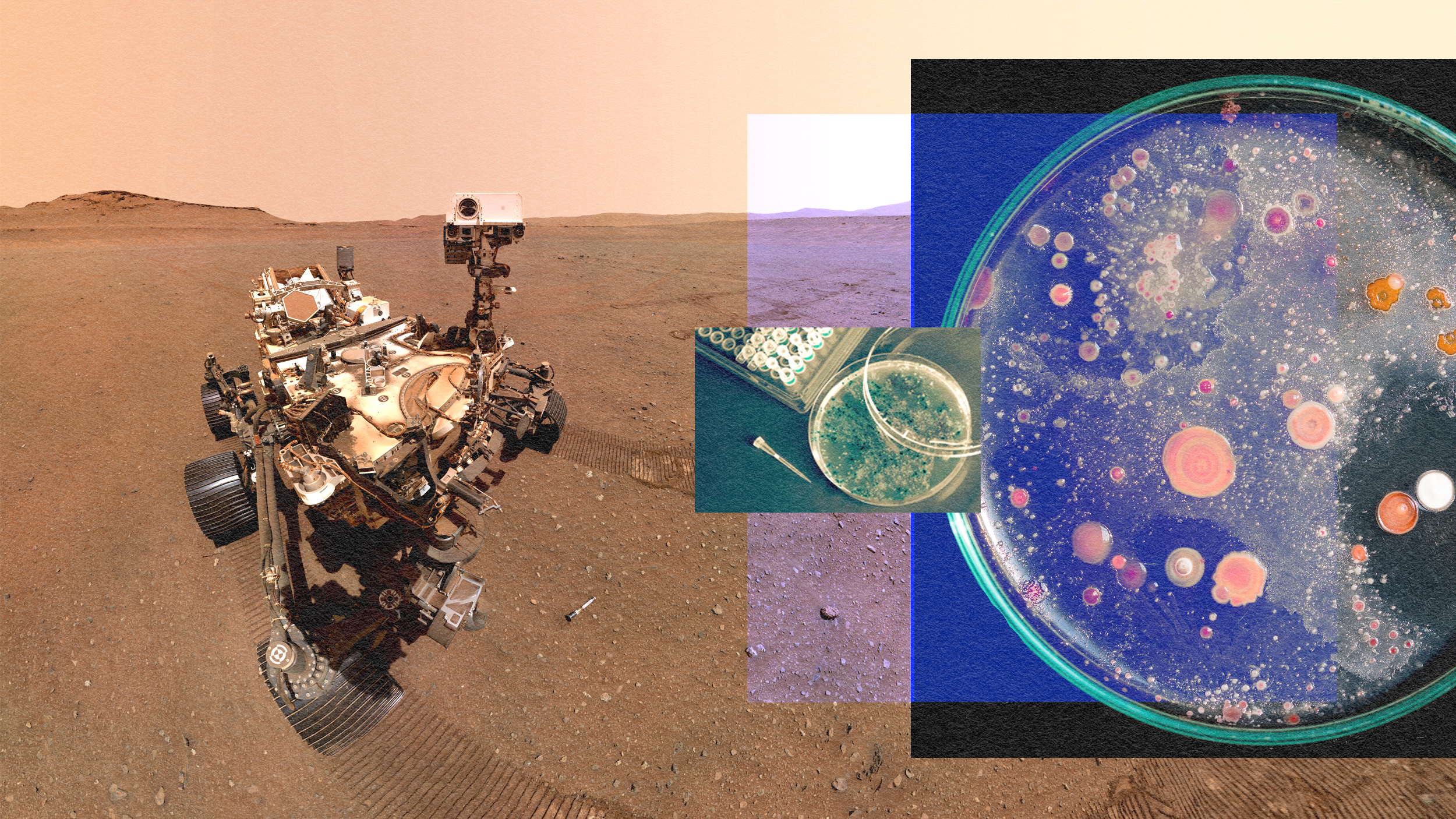

- In a recent study, researchers simulated the environment of ancient Mars and tested whether a type of extremophile found on Earth could grow on fragments of a meteorite from Mars.

- Extremophiles are organisms that have adapted to survive in conditions in which most life forms cannot, such as ice, volcanoes, and space.

- The results showed that the extremophiles were able to convert the rock into energy. What’s more, the microbes left behind biosignatures that could help scientists identify evidence of past life on Mars.

Scientists have successfully grown microcrobrial organisms on rocks from Mars, boosting the case that life could have once existed on the Red Planet.

The study, published in Communications Earth & Environment, involved tiny chunks of a Martian meteorite called Northwest Africa 7034, better known by its nickname: Black Beauty. The meteorite was discovered in the Sahara Desert, where it crashed around 1,000 years ago. Today, it’s worth 250 times the price of gold.

“Black Beauty is among the rarest substances on Earth, it is a unique Martian breccia formed by various pieces of Martian crust (some of them are dated at 4.42 ± 0.07 billion years) and ejected millions [of] years ago from the Martian surface,” study author Tetyana Milojevic, an astrobiologist at the University of Vienna in Austria, told Science Alert.

“We had to choose a pretty bold approach of crushing a few grams of precious Martian rock to recreate the possible look of Mars’ earliest and simplest life form.”

Ancient Mars probably looked a lot different than the planet does today. NASA data suggest that, billions of years ago, Mars was warmer, wetter, and had a thicker atmosphere, all of which are ingredients for the evolution of life. What kinds of life? It’s unclear, but extremophiles are a good bet.

Northwest Africa (NWA) 7034Credit: NASA

Extremophiles are organisms that thrive in conditions where most life forms would die. Scientists have observed them in volcanoes, soda lakes, Antarctic ice, and hydrothermal vents. Some have even survived the vacuum of space. The team behind the recent study focused on a particular class of extremophiles called chemolithotrophs, which are microbes that use inorganic compounds as a source of energy.

To test whether chemolithotrophs might have been able to evolve on Mars, the team placed a chemolithtrophic microbe called Metallosphaera sedula onto bits of Black Beauty. The researchers simulated the ancient Martian environment by keeping the microbe-covered rock bits in a bioreactor that controlled temperature and levels of carbon dioxide and air.

The high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image of the focused ion beam (FIB) section extracted for STEM analysis from the NWA 7034 fragment used in this studyCredit: Milojevic et al.

Using microscopy, the researchers saw that the microbe successfully converted rock pieces into biomass.

“Grown on Martian crustal material, the microbe formed a robust mineral capsule comprised [sic] of complexed iron, manganese and aluminum phosphates,” Milojevic told Science Alert.

“Apart from the massive encrustation of the cell surface, we have observed intracellular formation of crystalline deposits of a very complex nature (Fe, Mn oxides, mixed Mn silicates). These are distinguishable unique features of growth on the Noachian Martian breccia, which we did not observe previously when cultivating this microbe on terrestrial mineral sources and a stony chondritic meteorite.”

The study didn’t prove that chemolithotrophs or any other type of life ever existed on Mars. But the results did show that the chemolithotrophs left behind unique biosignatures as they converted the rock bits into energy.

With these fingerprints on the books, scientists working with the Mars 2020 mission might be able to find similar biosignatures in rock samples collected or observed by the Perseverance rover, which landed on Mars in February. Rock samples collected by the rover are expected to return to Earth in 2031.