Scientists observe strange behavior in universe’s strongest magnets

Credit: Carl Knox, OzGrav

- In a new study, scientists describe a magnetar’s bizarre behavior.

- Magnetars are neutron stars with extremely powerful magnetic fields.

- The strange space objects also emit radio bursts that reach Earth.

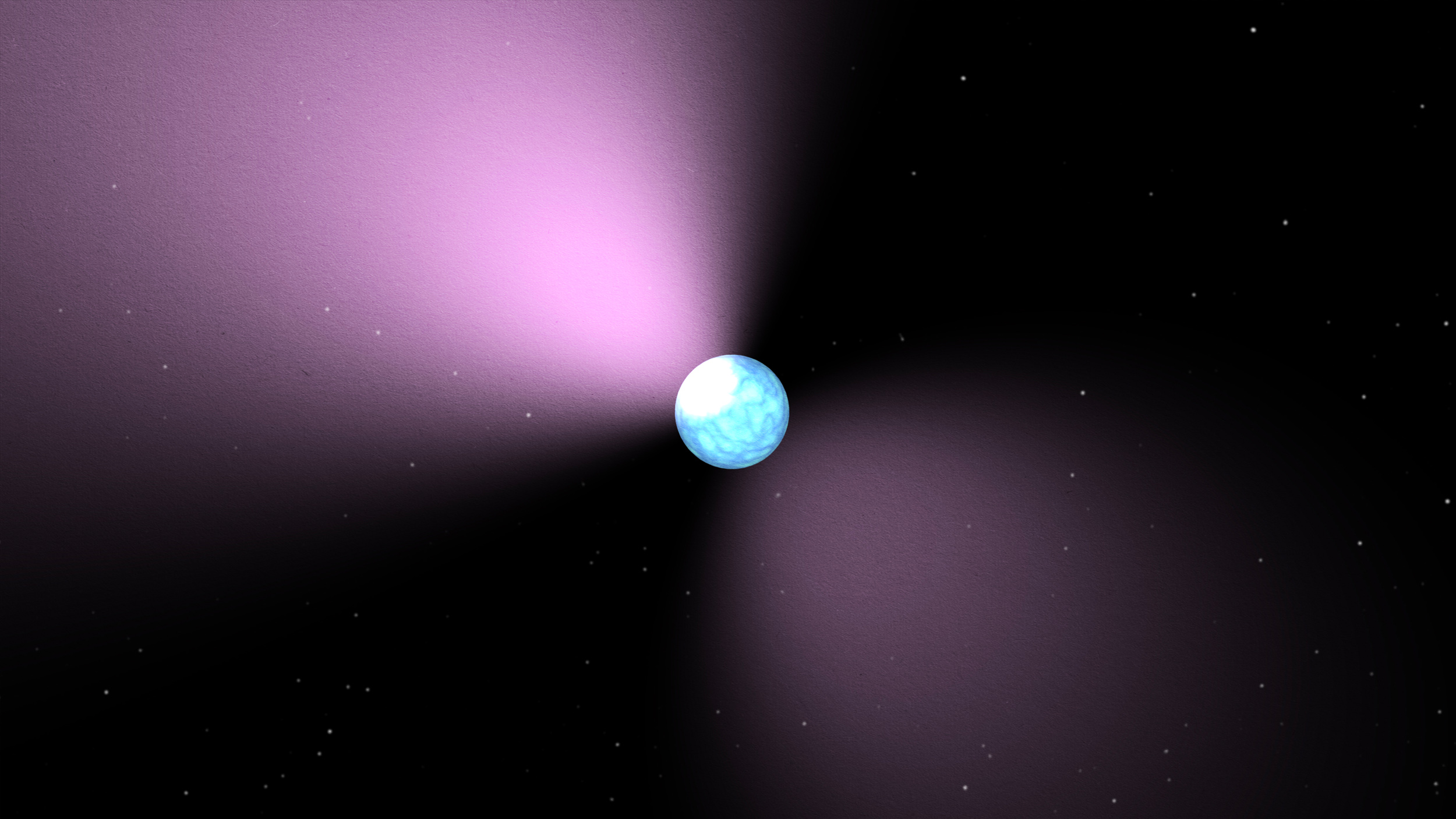

Astronomers recently witnessed very strange behavior from a magnetar, a peculiar kind of rotating neutron star that also happens to be one of the strongest magnets in the universe.

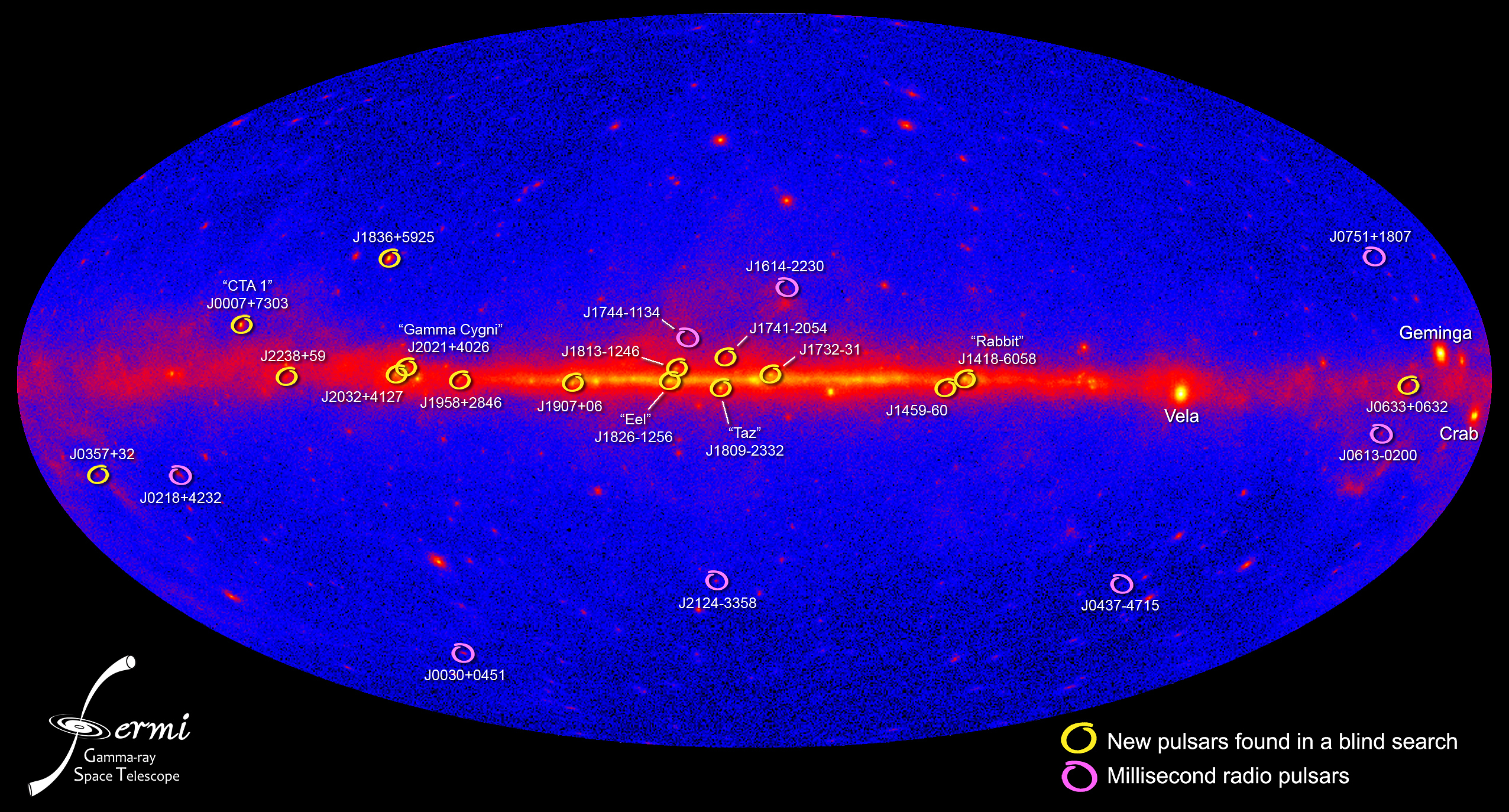

Magnetars are essentially remains of dead stars with amazingly strong magnetic fields that also emit mysterious radio signals. When a star dies, going supernova, about one in ten such explosions result in magnetars. Others end up creating neutron stars, or pulsars.

About 30 magnetars, each up to 20 km (12 mi) in diameter, have been spotted around the Milky Way. Imagine a magnet the size of a town flying by.

According to NASA, the strength of a magnetar’s magnetic field could be one thousand trillion times stronger than Earth’s. In fact, measured at up to 1 quadrillion gauss, the field is so intense that it heats the magnetar’s surface to an extra balmy 18 million degrees Fahrenheit.

To think about the magnetar’s power another way, NASA shared if a magnetar appeared about halfway of the distance between the Earth and the moon (238,855 miles), it could wipe out information from the magnetic strips of all credit cards on our planet.

A new study, carried out by scientists from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Gravitational Wave Discovery (OzGrav) and CSIRO in Australia, studied magnetars by largely relying on X-ray telescopes that looked for high-energy outbursts. Some times magnetars also send out radio pulses like pulsars, which are less magnetic. Why this happens and how such pulses change has been the focus of the research.

What Would Happen If You Fell Into A Magnetar? | Random Thursdaywww.youtube.com

The scientists studied pulses coming from the magnetar J1818, observing it eight times, and found some very inconsistent behavior. It started out sending pulsar-like signals, then began flickering and going back and forth between emitting like a pulsar or a magnetar.

The study’s lead author, Ph.D. student Marcus Lower of Swinburne University/CSIRO, elaborated on why this magnetar turned out to be so fascinating:

“This bizarre behavior has never been seen before in any other radio-loud magnetar,” said Lower. “It appears to have only been a short-lived phenomenon, as by our next observation, it had settled permanently into this new magnetar-like state.”

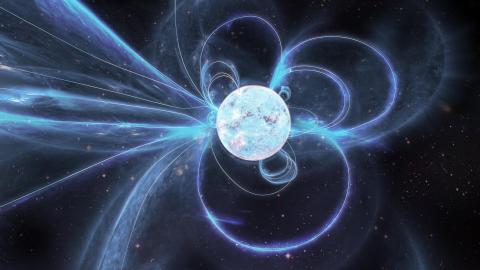

What the scientists found was that the magnetic axis of J1818 was not aligned with its rotation axis. Its radio signals come from the magnetic pole in the Southern Hemisphere, from below the equator. Other magnetars tend to have magnetic fields aligning with their spin axis.

Yet, while misaligned, the magnetic arrangement appears to be stable. The researchers concluded that the radio pulses coming from J1818 emanate from loops of magnetic field lines that join the two poles. This is different from most neutron stars.

The findings have bearings on magnetar simulations, leading to deeper knowledge of their creation and evolution. The scientists are looking to catch flips between magnetic poles to be able to map a magnetar’s magnetic fields.

Read the new paper, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS).