Iceland earthquakes hint at a new era of increased volcanic activity

- Over the last month, Iceland has witnessed hallmarks of an impending volcanic eruption: earthquakes, a swelling of the Earth, and leakage of volcanic gasses.

- Towns have been evacuated in southwestern Iceland as experts anticipate an eruption within the next three weeks.

- This geologic activity may be part of a thousand-year cycle. If so, eruptions in the area could continue for decades or even centuries.

Since October 2023, thousands of earthquakes have shaken the Reykjanes peninsula of Iceland. The small town of Grindavík, a fishing village on the southern coast, has been evacuated. In some instances, residents had only ten minutes to grab possessions and pets before leaving their homes — possibly forever.

Already, clouds of gas billow from massive fissures that have opened in roads, playgrounds, and parking lots. Toxic sulfur dioxide has also been detected. Not only do these telltale signs herald an imminent eruption that could threaten the town, they suggest that Iceland — whose volcanoes go through roughly 1,000-year cycles — may be about to enter a new era of increased volcanism that could last for hundreds of years.

Up and down

The Reykjanes peninsula of southwest Iceland juts out into the Atlantic Ocean and sits over a tectonic plate boundary called the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. It has a raw type of beauty, with kaleidoscopic geothermal springs and moss covering ancient lava fields. This peninsula is the center of Iceland’s volcanic activity, yet it has been relatively quiet for the past 800 years.

That may soon change. After three eruptions in the area in the last few years, it appears that Iceland might be gearing up for a fourth. A swarm of over 1,000 earthquakes hit the region on October 25th within a two-hour period. Since then, hundreds of earthquakes per day have been recorded. Most of these earthquakes are minor, but they indicate a significant change in the conditions belowground.

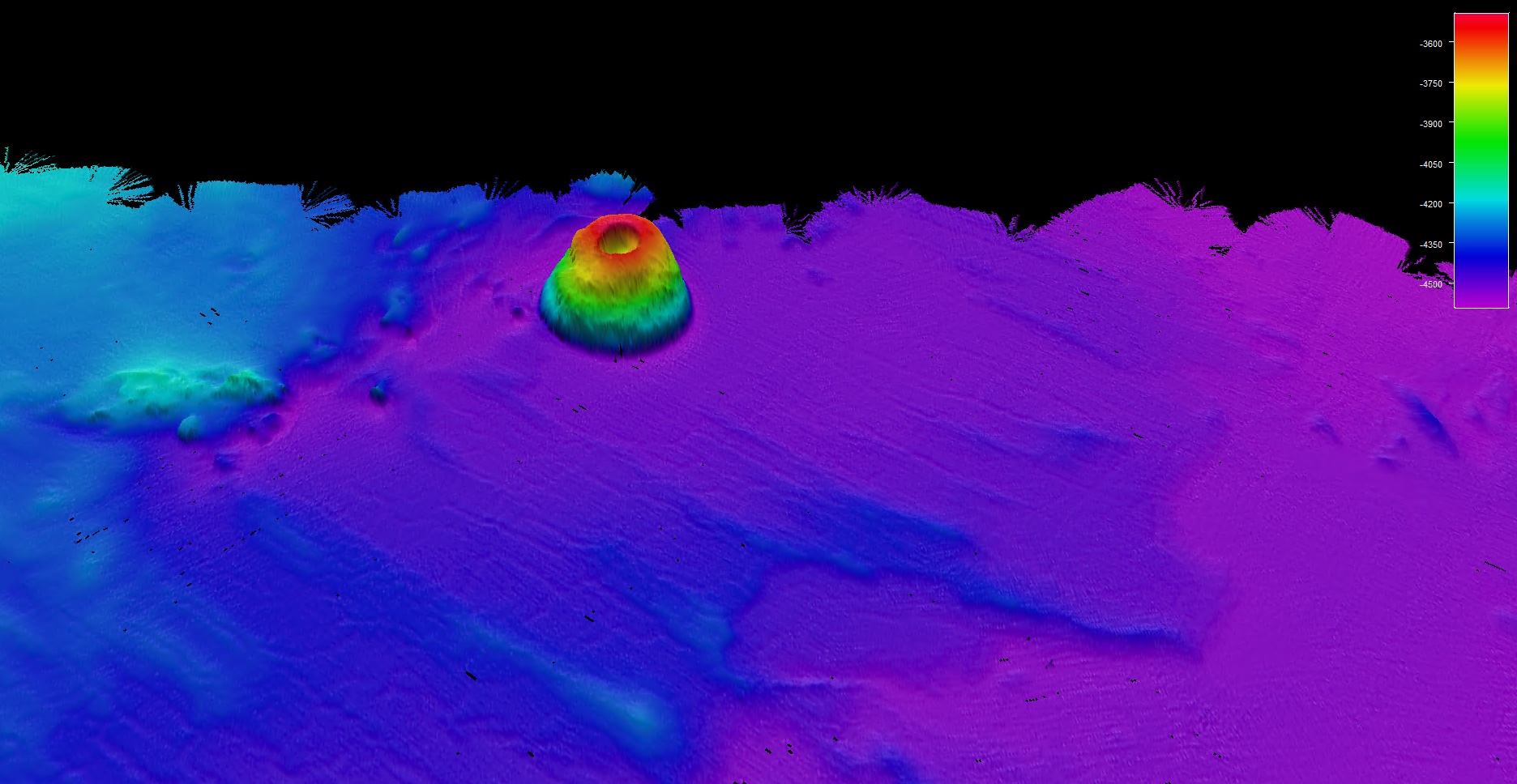

To understand what is happening, geologists turn to interferometry, a technique that uses radars and wave interference patterns to detect small changes in land elevation. Interferograms produced around November 10th to 11th showed that the region around Grindavík sank drastically – about a meter to a meter and a half. A more recent interferogram produced on November 18th to 19th showed that the same region has rapidly risen. The Icelandic Met Office reported that this change in elevation corresponds to an intrusion of magma, called a dike intrusion, pushing up against the ground of Iceland. It likely began forming on November 10th.

As of November 17th, scientists estimate that this magma intrusion is only 500 to 800 meters below the surface in a magma tunnel about 15 kilometers long. An eruption could occur anywhere along this tunnel. Situated nearby is the town of Grindavík, the Svartsengi geothermal power plant, and the popular tourist destination Blue Lagoon. Grindavík and Blue Lagoon have been evacuated, while Iceland’s largest bulldozer is creating a massive trench around Svartsengi in an attempt to divert lava if it heads that way.

The Icelandic Met Office also has been updating and releasing maps indicating where an eruption is likely. If an eruption is to occur, it is likely to happen within the next three weeks.

Iceland’s volcanoes

Volcanoes form in a few different locations on Earth. In the first, two tectonic plates converge. One plate is pushed under the other, forcing the other plate upward. The sinking plate, located in the subduction zone, eventually meets the mantle and begins to melt. Subduction zone regions are known for powerful earthquakes (like in California) and explosive, devastating volcanic eruptions (like Mount St. Helens).

Volcanic eruptions can also occur where two tectonic plates move apart from one another. At this divergent plate boundary, the mantle rises to fill the gap between the separating plates, creating volcanoes that erupt gently and gradually. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a prime example. Here, the North American and Eurasian plates move apart by roughly two cm per year. Iceland is part of this ridge, created by volcanic eruptions that occurred millions of years ago. Thingvellir National Park in Iceland is one of the only locations on the planet where the boundary of two tectonic plates can be seen on Earth’s surface.

Finally, volcanoes can form over a hot spot, where unusually hot magma rises through the mantle toward the crust. These can occur anywhere on a plate, sometimes even in the middle (like in Hawaii or Yellowstone) or near the edge, like in Iceland. Hot spot volcanoes typically erupt gently, but lava can still cause significant damage, covering roads and towns, starting fires, and explosively entering the sea.

A thousand-year cycle

Iceland‘s volcanism is due to a combination of a divergent plate boundary and a hot spot, but the region largely has been dormant for the past 800 years. Along with the eruption of Fagradalsfjall in March 2021, followed by eruptions in August 2022 and July 2023, this most recent activity indicates that the region has reawakened.