This is what aliens would ‘hear’ if they flew by Earth

Image source: sdecoret on Shutterstock/ESA/Big Think

- There is no sound in space, but if there was, this is what it might sound like passing by Earth.

- A spacecraft bound for Mercury recorded data while swinging around our planet, and that data was converted into sound.

- Yes, in space no one can hear you scream, but this is still some chill stuff.

First off, let’s be clear what we mean by “hear” here. (Here, here!)

Sound, as we know it, requires air. What our ears capture is actually oscillating waves of fluctuating air pressure. Cilia, fibers in our ears, respond to these fluctuations by firing off corresponding clusters of tones at different pitches to our brains. This is what we perceive as sound.

All of which is to say, sound requires air, and space is notoriously void of that. So, in terms of human-perceivable sound, it’s silent out there. Nonetheless, there can be cyclical events in space — such as oscillating values in streams of captured data — that can be mapped to pitches, and thus made audible.

Image source: European Space Agency

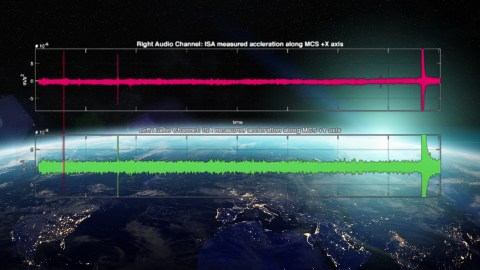

The European Space Agency’s BepiColombo spacecraft took off from Kourou, French Guyana on October 20, 2019, on its way to Mercury. To reduce its speed for the proper trajectory to Mercury, BepiColombo executed a “gravity-assist flyby,” slinging itself around the Earth before leaving home. Over the course of its 34-minute flyby, its two data recorders captured five data sets that Italy’s National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) enhanced and converted into sound waves.

In April, BepiColombo began its closest approach to Earth, ranging from 256,393 kilometers (159,315 miles) to 129,488 kilometers (80,460 miles) away. The audio above starts as BepiColombo begins to sneak into the Earth’s shadow facing away from the sun.

The data was captured by BepiColombo’s Italian Spring Accelerometer (ISA) instrument. Says Carmelo Magnafico of the ISA team, “When the spacecraft enters the shadow and the force of the Sun disappears, we can hear a slight vibration. The solar panels, previously flexed by the Sun, then find a new balance. Upon exiting the shadow, we can hear the effect again.”

In addition to making for some cool sounds, the phenomenon allowed the ISA team to confirm just how sensitive their instrument is. “This is an extraordinary situation,” says Carmelo. “Since we started the cruise, we have only been in direct sunshine, so we did not have the possibility to check effectively whether our instrument is measuring the variations of the force of the sunlight.”

When the craft arrives at Mercury, the ISA will be tasked with studying the planets gravity.

The second clip is derived from data captured by BepiColombo’s MPO-MAG magnetometer, AKA MERMAG, as the craft traveled through Earth’s magnetosphere, the area surrounding the planet that’s determined by the its magnetic field.

BepiColombo eventually entered the hellish mangentosheath, the region battered by cosmic plasma from the sun before the craft passed into the relatively peaceful magentopause that marks the transition between the magnetosphere and Earth’s own magnetic field.

MERMAG will map Mercury’s magnetosphere, as well as the magnetic state of the planet’s interior. As a secondary objective, it will assess the interaction of the solar wind, Mercury’s magnetic field, and the planet, analyzing the dynamics of the magnetosphere and its interaction with Mercury.

Recording session over, BepiColombo is now slipping through space silently with its arrival at Mercury planned for 2025.