New arthritis treatment uses nanoparticles to take drugs directly into cartilage

Pixabay Commons

- Osteoarthritis is a debilitating condition that affects millions of people worldwide, and the only treatments available merely reduce the pain.

- The new treatment delivers a growth factor into cartilage rather than into the surface of a joint, where it’d be less effective.

- The treatment represents a “significant step for nanomedicines,” one professor said, and it could someday be used to slow age-related osteoarthritis, a leading cause of chronic pain and lost productivity at work.

MIT engineers have successfully used nanoparticles to deliver arthritis-treating drugs directly into the cartilage of mice, a development that could greatly improve treatments for the debilitating condition.

The method is outlined in new paper published November 28 in Science Translational Medicine.

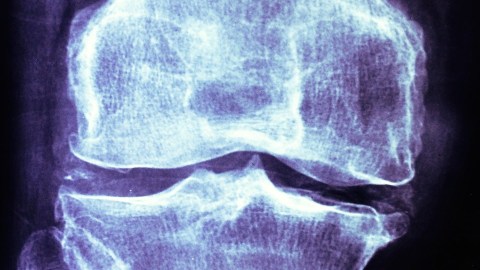

Osteoarthritis, a disease in which cartilage in joints gradually degenerates, currently affects more than 20 million people in the U.S. at an annual cost of about $60 billion. Worse are the costs of arthritis-attributable medical care, which have exceeded $300 billion in recent years. The condition can cause severe pain and impaired ability, and it often leaves people unable to work. But despite its far-reaching impacts, the only treatments currently available for osteoarthritis simply manage pain and symptoms.

The new treatment seeks to change that by delivering an experimental drug directly to the source of the degeneration. The goal was to deliver an experimental drug called insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) to cells within joints called chondrocytes, which are responsible for producing the cartilage that protects joints.

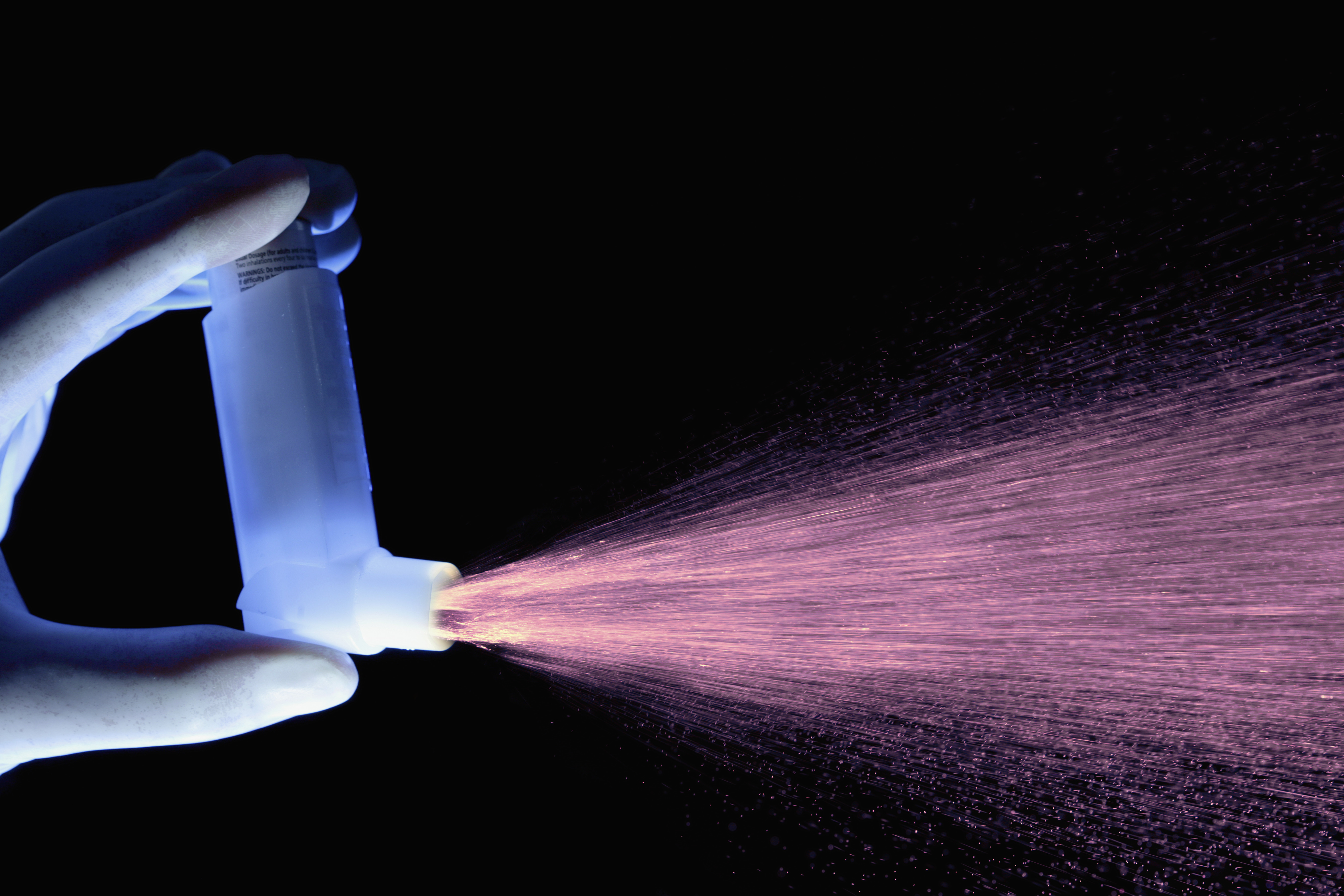

To do that, MIT engineers devised tiny sphere-shaped nanoparticles with branched structures, called dendrimers, whose tips maintain a positive charge that lets them bind to negatively charged cartilage. They then attached IGF-1 to these nanoparticles and injected them into the injured joints. From there, the nanoparticle-drug combination used its unique charge to travel deep into the joints, where it was able to bind to the chondrocyte receptors and stimulate cartilage growth.

Gieger et al.

After a couple of months, the researchers noticed not only reductions in joint inflammation and bone spur formation in the mice, but also that IGF-1’s therapeutic effects lasted significantly longer than current, experimental methods of delivery.

“Delivery of growth factors using nanoparticles in a manner that sustains and improves treatments for osteoarthritis is a significant step for nanomedicines,” Kannan Rangaramanujam, a professor of ophthalmology and co-director of the Center for Nanomedicine at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, who wasn’t involved in the research, told MIT News.

Still, using this same technique on human joints will require further research and passing clinical trials.

“That is a very hard thing to do. Drugs typically will get cleared before they are able to move through much of the cartilage,” Brett Geiger, an MIT graduate student, is the lead author of the paper, told MIT News. “When you start to think about translating this technology from studies in rats to larger animals and someday humans, the ability of this technology to succeed depends on its ability to work in thicker cartilage.”