Misunderstanding the End of History

What’s the Big Idea?

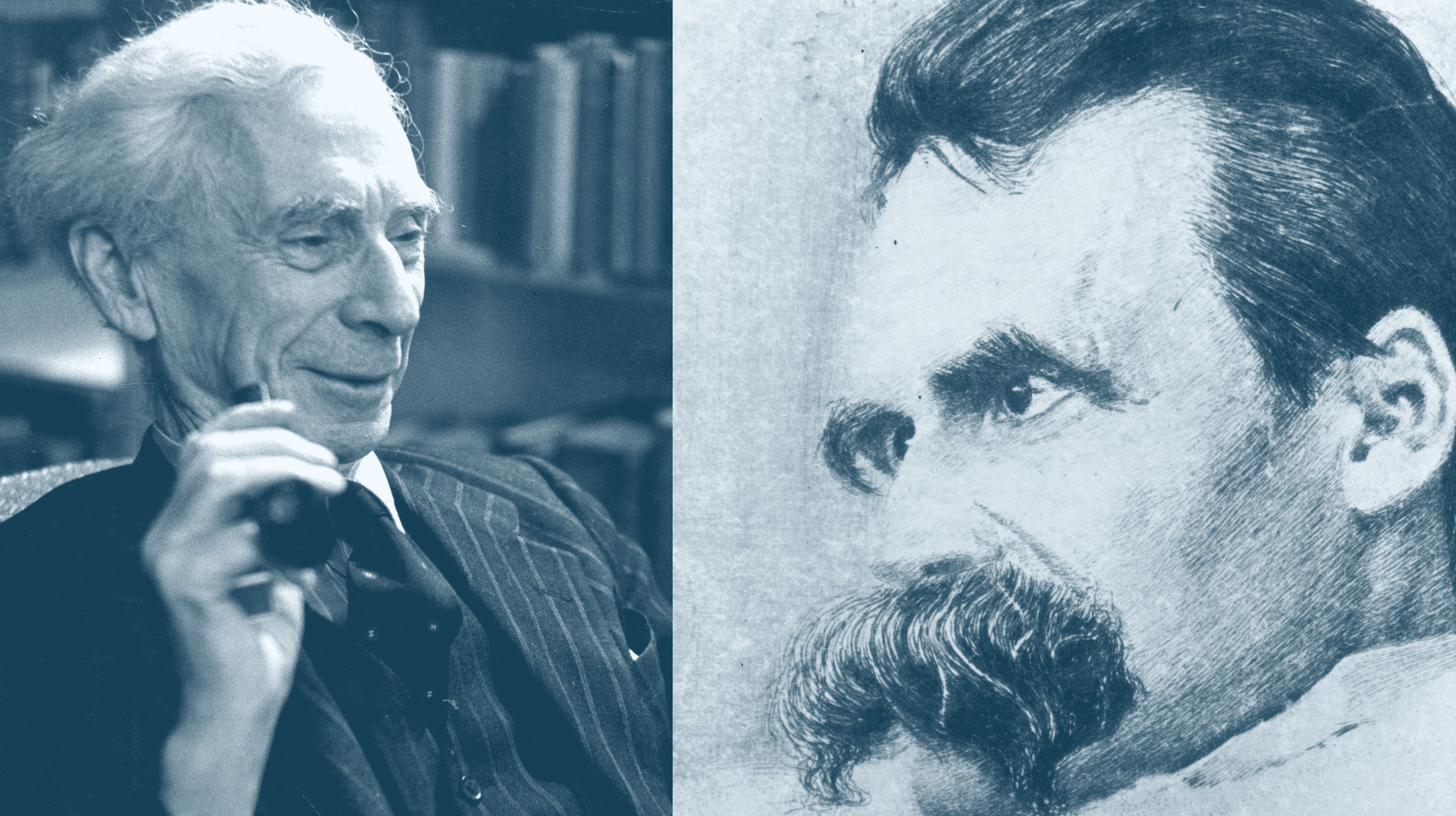

Francis Fukuyama wrote a book called The End of History in 1991, a which he told Big Think has “probably been one of the most misunderstood titles every concocted.” Of course, the title wasn’t actually Fukuyama’s invention. It comes from the German philosopher, Friedrich Hegel. Fukuyama says the main source of misunderstanding “was that people interpreted “End” as termination, you know, finishing.” However, “End” in that sense meant the goal or the objective of history.

The End of History is a key concept of Marxism: the belief that “history was progressive and it was going to end in a communist utopia.” Fukuyama also argued that history is progressive, but in his view, the collapse of the Soviet Union proved that communism would not be the final stage of man’s political development.

Instead, the end of history seemed to be stopping at the stage before communism, “which the Marxists called Bourgeois Liberal Democracy.” That is the political system of the United States and other western democracies, the model system that emerging democracies would inevitably follow.

What’s the significance?

Anyone who is concerned about how the tumultuous Arab Spring and other political upheavals will resolve themselves will be heartened by Fukuyama’s argument. It may not happen overnight, but history is leading us inexorably toward a state where democratic capitalism has completely won out.

Fukuyama says those who reject his argument must answer this question: “If you don’t believe that this is the end of history, what’s beyond? You know, are we going to evolve into a Taliban-style Islamic republic? I really doubt it. Are we going to evolve into a Chinese Authoritarian Dictatorship? Well I sort of doubt that also, at least for America and Europe and other places that are wealthy democracies today.”

What lessons can be learned?

Fukuyama links the difficulty of communicating his idea of the end of history to a problem he says plagues serious discourse in general today. The greatest challenge for any author is getting people’s attention. Fukuyama told Big Think that “unfortunately, a lot of people try to outbid each other in saying things that are outrageous. And I think people have accused me of that in terms of the title of my book. But I think the better way to grab attention is to take a big idea and say something interesting about it.”

Fukuyama argues that our academic culture works against this. “Everybody is compartmentalized into these little disciplines,” he says, “and they see little points and they don’t really see the big picture. And unfortunately, the way we train people in universities and in school really encourages this sort of narrow specialization.”

In Fukuyama’s view, specialization has led to, among other things, the demise of the public intellectual–people like Daniel Bell or Nathan Glazer or Irving Howe. Fukuyama says there are “not that many of them any more because of the specialization of academic life.”

“But I think that in some sense intelligent discussion of public issues that brings to those issues not just the kind of opinion that you see in all of the blogs or all of the talking heads on TV, but that brings real information to people is something that people will appreciate.”