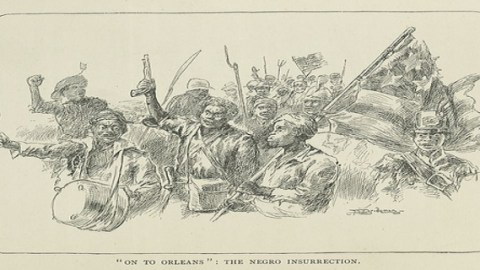

American Uprising Revisits Louisiana’s 1811 Slave Revolt

If the adage “history is written by the winners” is true, then what does that mean for African American history, especially now that more W’s are slowly but surely showing up in our won-loss column? How hard will it be to convince the rest of America to replace the commonly accepted falsehoods and deliberate omissions about the history of black Americans with the fruits of careful scholarship? Daniel Rasmussen, a recent Harvard graduate, has decided to step up to the plate and take a whack at righting the historical record with American Uprising:The Untold Story of America’s Largest Slave Revolt, a brief but cogent narrative that reinterprets the circumstances surrounding the largest slave revolt in American history.

Much of African American history has been ignored or suppressed for centuries. Most of what I know about African American history has come from reading on my own. There was no mention of the Rosewood massacre, or the Tulsa race riot, or even the Orangeburg massacre, an infamous event that happened right there in my hometown, in any history books I studied in school. The only thing we covered, probably because I was in South Carolina, was the Denmark Vesey led uprising. Even in college, the African American studies classes I took only went so far. Which is why I was excited last week to get my review copy of American Uprising.

Most of the preconditions necessary for the Louisiana uprising chronicled in American Uprising to happen revolved around the Haitian slave uprising, the takeover of the Spanish colony of West Florida by the United States, and the propensity of the slave trade in New Orleans to force into captivity thousands of young African men recently abducted from their homeland. So I can understand the importance of carefully setting the scene. Nevertheless, here Rasmussen is wanting – there were too many pages in the beginning of the book that left me feeling as if he was beating around the bush.

It wasn’t until the author began to work his way up to the day the German Coast rebellion actually started in earnest that I reconsidered his decision to take so much time to set the stage for this massive but little known Louisiana slave uprising. Stylistic and structural differences aside, the real power of the book lies in its refutation of established history. As objective as I’d like to be, there is no way around the uneasy feeling I get whenever I see the word “slave” in print, especially when the rituals of slavery are being dissected. As Charles Deslondes and Kook and Quamana, who are the leaders of the revolt, begin to put their plan in motion, I see the same elements of the plans John Brown and Nat Turner had to liberate slaves taking shape. It wasn’t until I read the words “and their group now numbered somewhere between 200 and 500 men” that I realized this uprising was different.

At that point, Rasmussen’s carefully laid out backstories all began to work together to heighten the drama, so much so that even though I knew how the story was going to end, I still found myself playing “what if the slaves had done this instead?”

One phrase in particular popped out at me while I read. It was the kind of judgmental declaration that was not normally the kind of thing you see in a historical accounting of America.

“[William] Claiborne succeeded in preventing the uprising from becoming a part of the larger political discourse- and in doing so laid the groundwork for the collective amnesia about the 1811 uprising in historical and popular memory.”

From American Uprising

For me, Chapter Sixteen was the most interesting. Here Rasmussen demonstrated quite effectively how easily the official historical narrative could veer away from the actual events of the past. He also singled out Leon Waters, an African American native of Louisiana who mounted a campaign to unearth more information about the Louisiana slave revolt than what was handed down to him orally by relatives.

My own preference is for big, thick, exhaustively researched history books that claim significant chunks of the author’s lives. American Uprising could have benefited from the kind of revisions that can only come when an author spends enough years with a subject to give their narrative a more organic rhythm. But since it looks like the author is just getting started, I would expect, five or ten years from now, to be able to sit down to a nice, big, thick book on this very same topic, one that has an older version of Daniel Rasmussen pictured on the book jacket.