Could deadly viruses’ rapid evolution be turned against them? And could we ever control the pace of our own evolution?

Question: What is lethal mutagenesis and how would it work?

rnCarl Zimmer: So we have this problem with fighting viruses. The problem is that really the only kinds of ways we have to deal with viruses are old school, so vaccines for example are very effective, but the first vaccines were invented in the 1700’s, so we’re talking about technology that is over 200 years-old. Another good way to fight viruses is for having people wash their hands. That’s actually slightly younger in terms of technology. That was in the 1800’s that people figured that out, but still we’re talking about stuff that is over a century old, so scientists are looking for new ways to fight viruses and one possible way that scientists are looking into is to basically turn the viruses own strengths into weaknesses. Now the reason that viruses are so hard to fight, the reason for example we need a flu virus every year is that they evolve very fast. When you get sick with the flu you get infected with flu viruses and they make lots of new flu viruses, but those new viruses are not exact copies of the old ones. They have mutations in them. A lot of those mutations are harmful. They just kill the virus, but some of them are beneficial, so for example they might make it difficult for our immune systems to attack them and so those flu viruses that can evade our immune systems they’re the ones that take off and they dominate the population and then there are new mutants and new ones and new one and now ones and natural selection keeps driving the rapid evolution of flu viruses that we have a hard time grappling with.

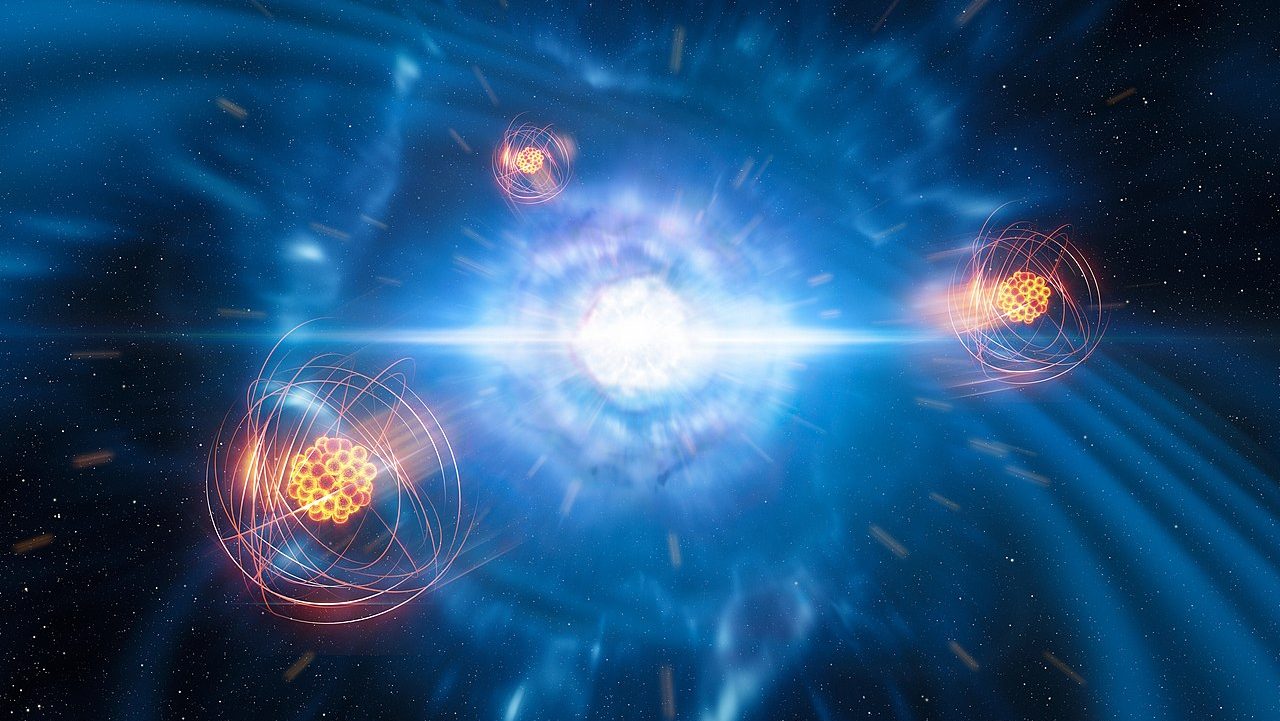

rnWell there is some research that suggests that viruses like the flu are really actually kind of at the razor’s edge when it comes to mutation. They’re mutating so fast that if they mutated much faster they would actually develop a lot of harmful mutations that could slow them down and cripple them and eventually literally drive them extinct. So the thinking is that maybe we could give people drugs that would speed up the mutation of viruses, so you get sick with the flu and your doctors says, “Here, take this drug.” It’s going to speed up the mutation of those flu viruses inside of you. It’s not going to harm you. It’s not going to harm your mutation rate. We’re not going to give you cancer here. We’re going to attack those viruses. And so the viruses start mutating faster and faster. They get more and more harmful mutations and then all the flu viruses in your body, the whole population just goes into the ground. It just becomes extinct. So scientists can make this work in dishes with cells and there is even some suggestion that this may be how some antivirals actually work right now and just people haven’t realized it and so scientists are trying to take that, the next step and so they’re developing this method, which is called lethal mutagenesis to apply it for, for example, HIV, so there are going to be some clinical trials starting to test out some of these drugs to try to drive HIV extinct within people’s own bodies.

rnQuestion: Could the speed of human evolution ever be controlled?

rnCarl Zimmer: I think we have actually already taken control of human evolution to some extent. We’ve actually changed the rate of human evolution just with our activity. You can go back to the invention of agriculture for example, so all of the sudden people who could digest certain kinds of foods because they had certain kinds of genes were going to be at an advantage over people who couldn’t and you can see this in the human genome if you look for example at milk and people who can digest it and people who can’t, so lactose intolerance that a lot of people suffer from you find that in people who descend from ethnic groups who did not traditionally raise cows whereas if you look at some populations in Europe where they raised cows or the Massai in Africa who were cattle herding people you can actually see the mutations that have allowed them to digest milk as adults. I mean everybody can digest milk when they’re little. I mean that’s what makes us mammals, but evolution has led to some populations of people being able to digest milk without much trouble when they’re adults as well. Now that was thousands of years ago, so basically we have been controlling our own evolution without realizing it for thousands of years and I think that we’re only going to continue to alter our own evolution even more in the future because we’re interfering in a good way with nature.

rnSo medicine, for example, you know, medicine allows people to live who would otherwise die, so antibiotics will let people survive infections that they might be otherwise very vulnerable to and even little things might make a big difference, so I wear eyeglasses because my eyes aren’t particularly strong, before there were eyeglasses someone at my age would probably not be good for much. You know I wouldn’t be a very good hunter without these glasses. I’m not a very good hunter with these glasses, but I’d be even worse without them, so that would put a crimp in how many kids I could have, so all of these medical advances have at least in some parts of the world blunted natural selection. Scientists call it relaxing natural selection and so that’s going to continue in the future at least as long as we have medical advances and the quality of life improves around the world, but that being said there are lots of ways that natural selection is just going to keep changing us. So for example, there are still plenty of parts in the world where people rarely if ever see a doctor where there are lots of serious diseases like malaria or HIV and so people are in a sense at the mercy of these pathogens and if they have the genetic wherewithal to be more resistant to these things they’ll be more likely to survive than others and that is natural selection right there. So that’s going to be happening as long as we have this horrendous inequity in the world where you know where billions of people can’t even get clean water, where they don’t get much medical attention.

rnOn the other hand, even in a place like the United States natural selection is going on right now. So for example, there was a study that scientists did of a town in Massachusetts called Framingham, and it was just a medical study. They wanted to track people’s health over decades and so there were thousands of people in Framingham and these doctors just took all their vital statistics year in, year out and when a new generation was born they started looking at those people as well, so they have this generation by generation record of how many kids people have and their health and so on and they can look to see well what kind of traits are shared by parents and their kids and they can actually see that the new generation of Framingham is a little bit different than the old generation. In other words certain people in Framingham had genetic traits that made them a little bit more likely to have more kids than the others. So for example, the women in Framingham are a little bit shorter on average than their parents were and there are lots of other traits that are becoming a little more common and so you repeat that and repeat that and repeat that in the future and that is natural selection happening as well.

Recorded on January 6, 2010

Interviewedrn by Austin Allen