Early usage of schadenfreude in English and literature

Edwin Booth playing Iago in Shakespeare's "Othello, the Moor of Venice." Image source: United States Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons

- Aristotle spoke of the emotion more than 2,000 years ago.

- The first appearance of the word in English-speaking countries gave speakers a new way to express themselves.

- To this day, there is still some unease around the feeling.

Schadenfreude — the word really rolls off the tongue, doesn’t it? This German word we’ve co-opted, perfectly encapsulates one of our most complex of feelings. That is, according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the pleasure derived from another person’s misfortune. Yes, the many multi-faceted emotion that, apparently, comes in a few types. . .

From the get-go, English-speaking people have had a complicated relationship with both the word and the feeling behind it. Schadenfreude has been a central emotional tenant of literature, philosophy, and general storytelling before we even knew what to call it.

Schadenfreude first graced the English page in 1853, by a devout and dour Richard Chenevix Trench, who would later go on to become the Archbishop of Dublin. Regarding the German word, he lamented its existence:

“Thus what a fearful thing it is that any language should have a word expressive of the pleasure which men feel at the calamities of others; for the existence of the word bears testimony to the existence of the thing. And yet in more than one such a word [like schadenfreude] is found.”

Before we had angry moralists waving their fists about a perfectly normal human emotion, the Greeks got to it first. Some Greek references go all the way back to the works of Aristotle, where he references the misfortunes of others with the Greek word epichairekakia.

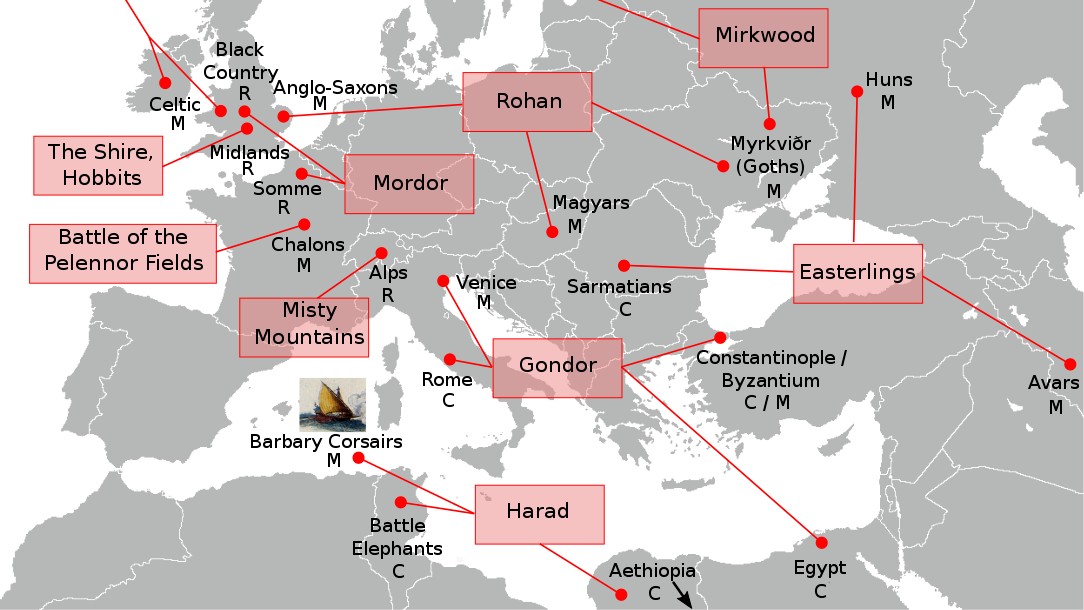

It turns out that a lot of different languages, indeed, have a word for this feeling. And its usage is implicit in not only their literature, but their culture as well.

Schadenfreude as a central literary theme

A majority of these words are compounds of the two words “harm” and “joy.” The Danish have skadefryd, the Dutch leedvermaak, French joie maligne, and the list goes on and on. There are of course a few languages that don’t have such a word, at least not yet.

Harvard-based cognitive psychologist and linguist, Steven Pinker, remarks about the ubiquitous nature of the feeling, regardless of whether or not the language has created its own word for the feeling. He states:

“The common remark that a language does or doesn’t have a word for an emotion means little. . . When English speakers hear the word schadenfreude for the first time, their reaction is not ‘Let me see… Pleasure in others misfortunes. . . What could that possibly be? I cannot grasp the concept; my language and culture have not provided me with such a category.’ Their reaction is, ‘You mean there’s a word for it? Cool!'”

The object of schadenfreude is a common theme that’s usually easily inferred in literature and in rare cases explicitly stated.

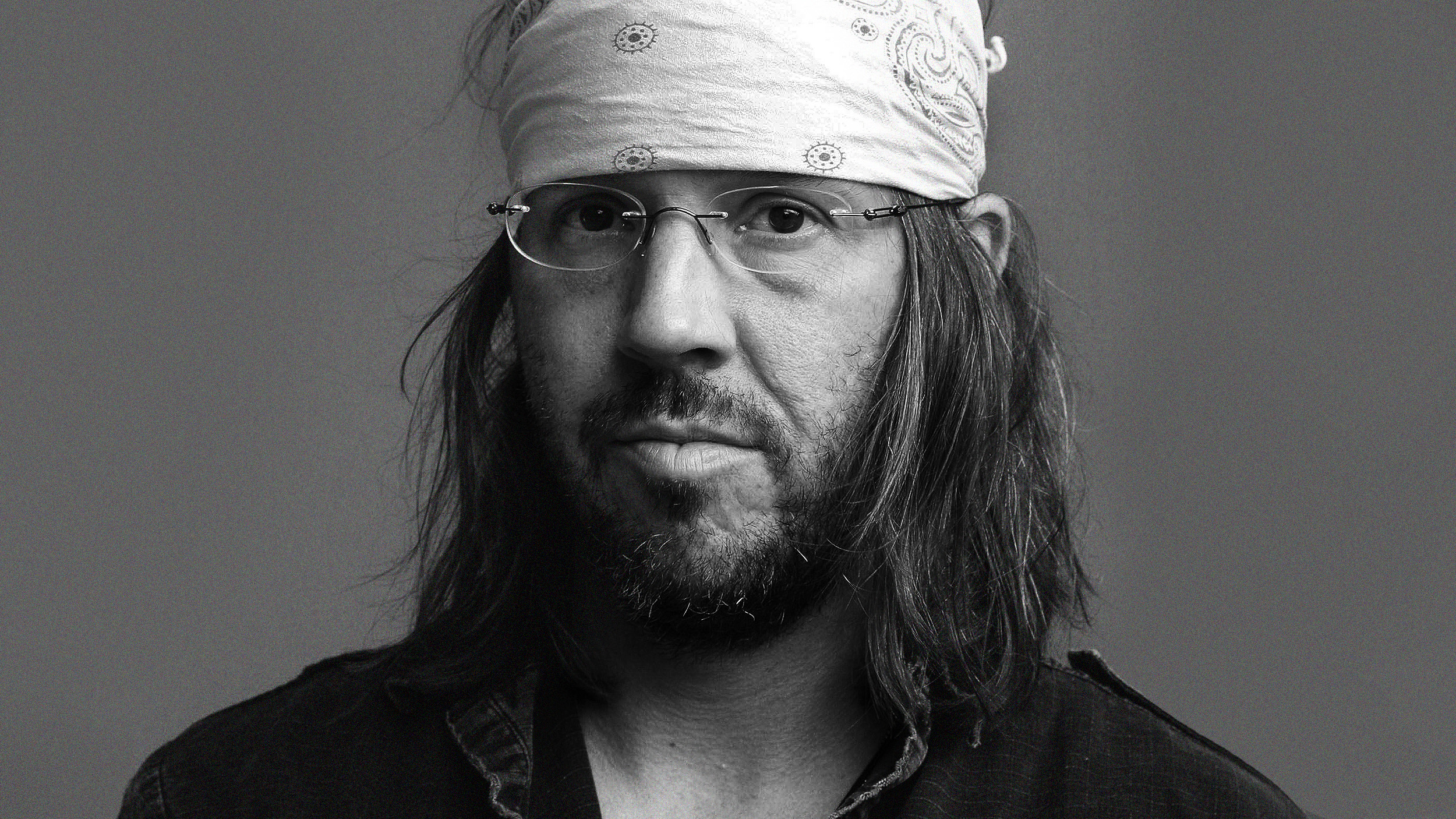

In psychologist Wilco W. van Dijk’s book Schadenfreude: Understanding Pleasure at the Misfortune of Others, the author delves into literary instances of schadenfreude. In the case of Shakespeare’s Othello, the characters of Iago and Cassio are prime examples of humans led by envy to bring about the destruction of individuals while being satisfied in the event. Yet they do not derive pleasure from it in a sadistic manner. Merely, this is a type of competitive schadenfreude.

While they perform cruel or what could be considered immoral acts, they are not sadists. Instead van Dijk feels that in literary cases such as these, writers such as Shakespeare are evoking core human sentiments — while extreme in the boundaries of regular experience, these feelings still do not constitute any kind of sociopathy — or psychopathy — in terms of fixed personality traits.

It’s important to make this distinction clear, so you can better grasp the feeling of schadenfreude in more common or modern works.

Take, for instance, the downfall of any half-rate villain in a movie or novel. Even just some regular person violating social norms, schadenfreude is that feeling we get when we believe someone deserves their suffering and we revel in it.

Countless stories and films resonate with this kind of feeling as a central emotive plot point. You’ll know it when you see it.

Thomas Carlyle. Image source: Elliot & Fry / Wikimedia Commons

Schadenfreude entering the English vernacular

Once the word was brought to the forefront, people had varied reactions to it. In 1867, the Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle admitted to feeling schadenfreude while he imagined the potential chaos that would come from the passing the Electoral Reform Act, allowing working-class men the right to vote.

Dr. Tiffany Watt Smith, cultural historian and author of Schadenfreude: The Joy of Another’s Misfortune and The Book of Human Emotions, goes into great detail in her book about the early usage of the term in popular culture during the 19th century.

One such hilarious instance was from 1881 when “a chess columnist advised persuading naïve opponents to use a tricky strategy, just to ‘indulge in what the Germans call ‘schadenfreude’ when they invariably floundered.”

Or another more malicious form when a physician by the name of Sir William Gull, pioneer of a healthy living movement in Victorian England, who self-righteously preached about drinking water and a form of vegetarianism suddenly became seriously ill.

“He went about giving self-righteous talks about how his lifestyle would protect him from diseases. So when in 1887 it emerged that he had become seriously ill . . . Well, reported the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent gleefully, there was ‘a certain amount of what the Germans call schadenfreude’ among advocates of ‘fuller diet and freer living.'”

Still, there were many Victorians and even modern day people that aren’t too fond of the idea of schadenfreude.

Dr. Smith remarks how the modern psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen pointed out that “psychopaths are not only detached from other people’s suffering but might even enjoy it.” Many modern day moralists believe that, on the worst end of the spectrum, schadenfreude is some kind of anti-empathy.

Van Dijk’s book explores the equally ambivalent response that many 19th-century American authors gave to the emotion as well. As taboo as the sentiment was in England, it held a similar status for those in the United States — references to schadenfreude was seen as overwhelmingly negative.

In the end, the culture is partly responsible for how the emotion is portrayed morally. Van Dijk suggests that, “It is not unlikely that contemporary American novels have more diverse approaches to schadenfreude than the nineteenth-century texts do.”