Study shows why face shields don’t work as well as face masks

Credit: Siddhartha Verma, Manhar Dhanak, John Frankenfield

- A new study provides a visualization of why face shields are ineffective at stopping the spread of COVID-19.

- Using a mannequin that could simulate coughing, the authors demonstrated how water droplets slide around shields.

- The authors conclude that shields are not an effective replacement for masks.

Face masks are everywhere these days, and for very good reason. They are proven to help reduce the chance of spreading COVID-19 by limiting how far water droplets people exhale can go, and most establishments won’t let you in without one. Despite this, complaints about wearing them abound.

A common and all too human one is that they prevent people from seeing your facial expressions, a key element of human communication. Others protest that masks are uncomfortable, and people who need glasses are quick to tell you that masks often cause glasses to fog. Many have tried using face shields, large plastic screens, in place of a proper mask to avoid these issues.

While the CDC already stated that face shields are not recommended as a replacement for face masks, a new study offers a visualization of the price you pay in protection in exchange or an ounce of comfort.

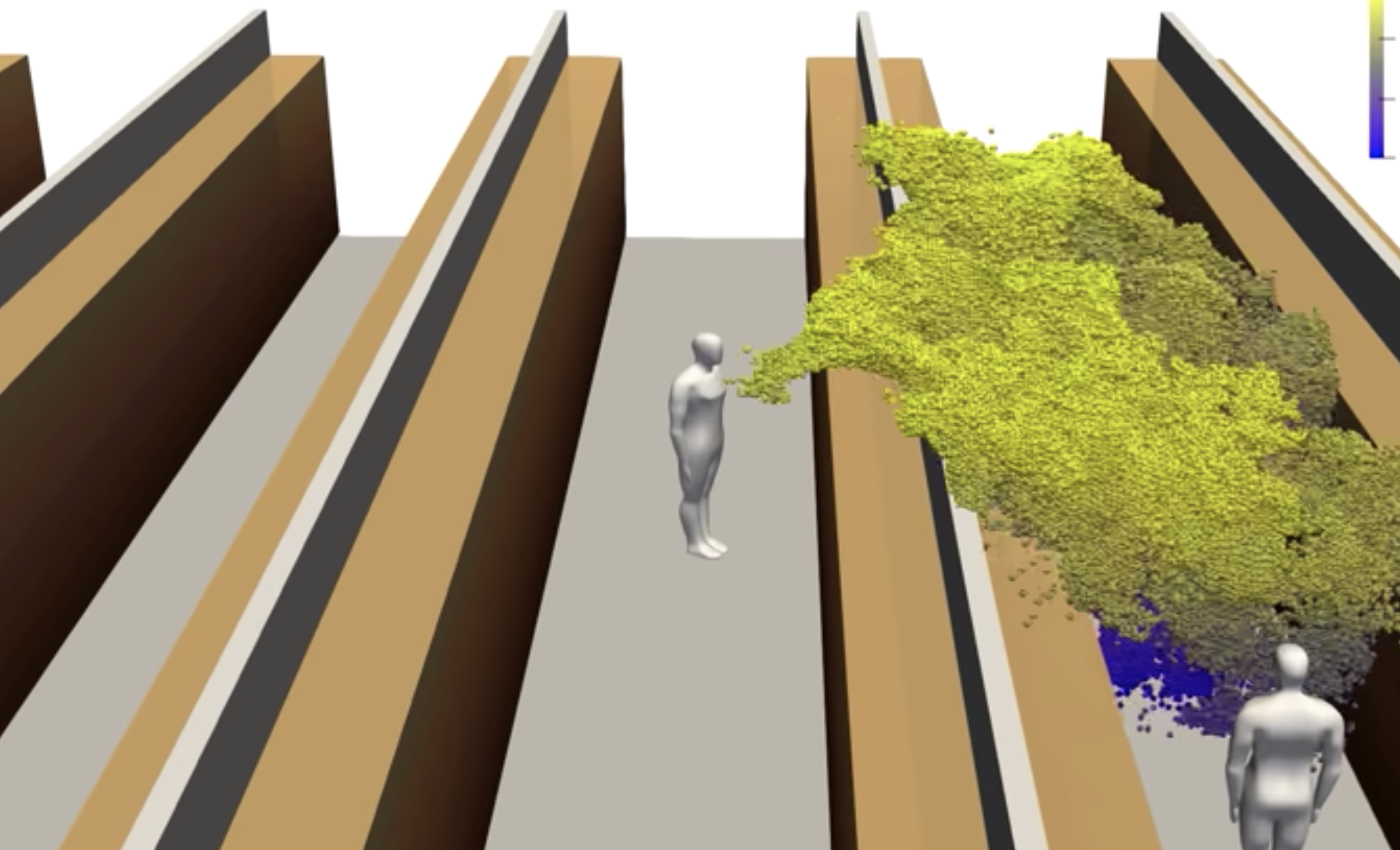

The straightforwardly named “Visualizing droplet dispersal for face shields and masks with exhalation valves” was published in the journal “Physics of Fluids” and led by Dr. Siddhartha Verma of Florida Atlantic University. In it, the researchers explain that while face shields are very good at blocking the forward motion of larger droplets of water, the large open space in their design allows for smaller droplets to pass them and disperse throughout the room, reducing their potential benefits.

The authors attached a face shield to a slightly modified mannequin that could simulate coughing to demonstrate this. Small droplets of water and glycerin, comparable in size to the lower end of estimates of what is needed for a virus to travel, were blown through the mannequin’s mouth and highlighted with laser sheets as they traveled throughout the room.

As illustrated below, small droplets that stop moving forward do not immediately drop to the floor, but instead, they float toward the gap at the bottom of the shield. Following air currents, the droplets eventually made their way around the face shield and began to spread. Given enough time, they’ll spread up to a few feet away.

Dr. Verma explained the weaknesses of face shields to the New York Times:

“Masks act as filters and actually capture the droplets and any other particles we expel. Shields are not able to do that. If the droplets are large they will be stopped by the plastic shield. But if they are aerosol sized, 10 microns or smaller, they’ll just escape from the sides or the bottom of the shield. Everything that is expelled will very likely get distributed in the room.”

The authors note that the water droplets’ concentration is reduced by wearing a face shield, meaning that fewer droplets are spread than would be spread by a person without any protection. The benefits of this are limited, though, and a previous study carried out by the authors of this test also shows how much more effective proper face masks are than face shields. Another study from 2014 gives face shields a mere 23 percent efficiency at reducing the inhalation of such droplets.

It should be no surprise, then, that the study concludes that face masks are preferable to face shields when it comes to slowing the spread of COVID-19.

The study also considered face masks with exhaust values, as shown in the final test in the above video. Face masks with exhaust values allow unfiltered droplets to go through the valve. Why they don’t do much to prevent droplets from spreading everywhere is obvious. Just as with face shields, the droplets that are initially unable to move forward eventually manage to get to the same place through dispersion.

How to shut down coronavirus conspiracy theories | Michael Shermer | Big Thinkwww.youtube.com

The shortcomings of face shields and other mask alternatives are not shared by the thing they are meant to replace, the basic, well-made face mask.

As explained above, face masks work to keep others around you from getting your germs by keeping the water droplets you exhale, which may contain viruses, from spreading. They have also been shown to reduce the number of droplets from other people’s breath that reach your face, potentially preventing you from getting sick. Given that face masks lack a large hole in them, as shields or masks with valves do, they allow far fewer droplets to escape than the competition.

The study considered the differences between a cheaply made face mask and a well-made one, with the cheap one proving much less effective. Even the best masks have some degree of leakage, so maintaining social distancing of at least two meters (about six feet) is still necessary.

No protective mask is perfect, and no set of rules offers complete safety. However, some objects and procedures work better than others at keeping people safe. As this study shows, face shields, masks with exhaustion valves, and cheaply made masks don’t work as well as a well-made face mask.