Why we should end the fantasy of the “Turnaround CEO”

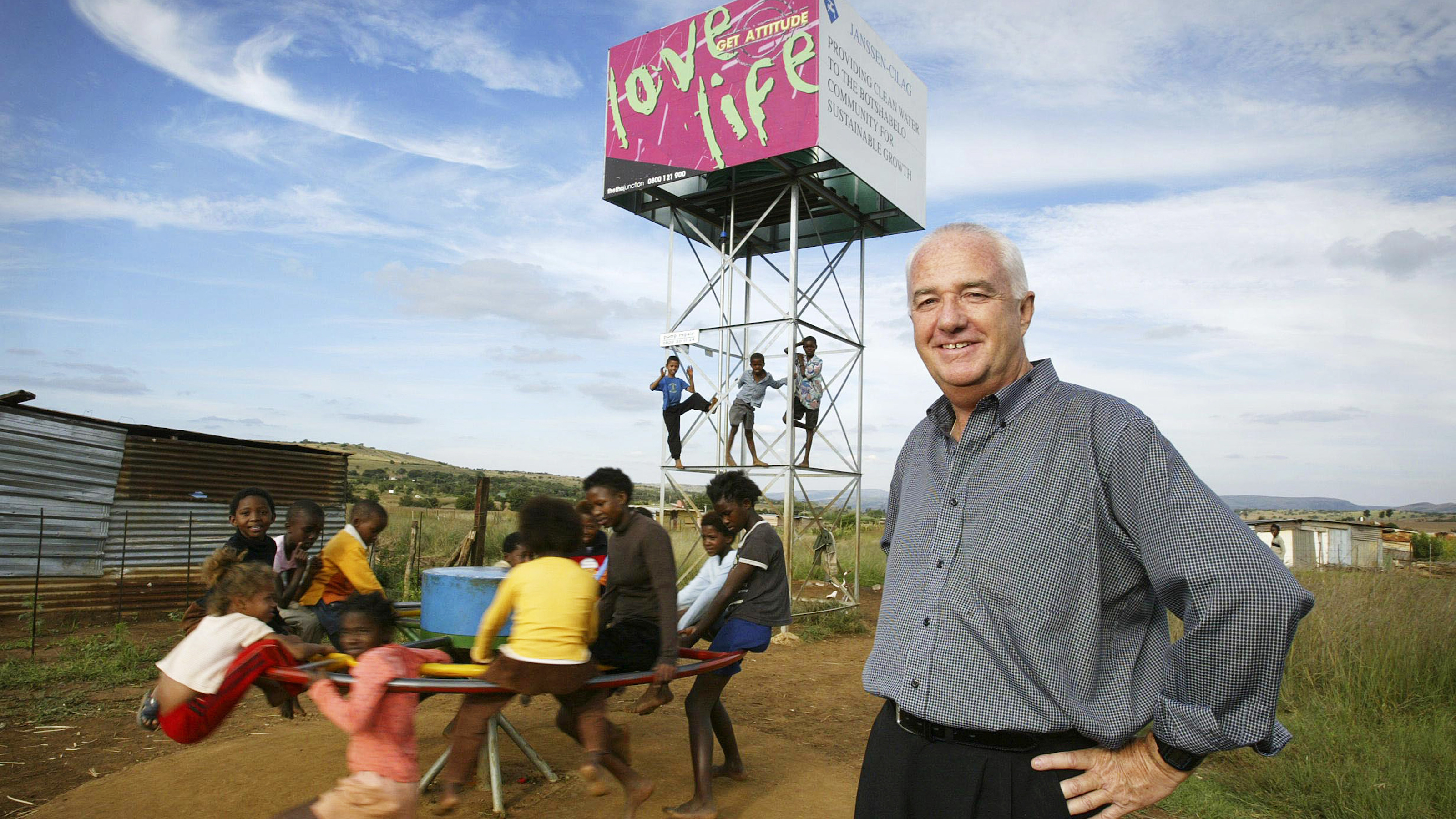

Credit: Gilberto Tadday / TED / CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 / Creative Commons

- The cash-transfer model of global aid offers a lesson in radical humility.

- Based on the success of “direct giving” there is an opportunity to invert our entire mental model of leadership.

- All leaders can ask: what is their industry’s version of “direct giving”?

When I was put in charge of the UK’s $20 billion global aid budget, it was easy to imagine I had “power.” I was a Secretary of State, appointed by the Queen. I had people working for me all over the world. Every day, I was asked whether I wanted to put $100 million into education in Ethiopia, or $40 million into healthcare in Nigeria? To contribute a billion dollars to a global fund on vaccines, or launch a new bank to invest in renewables?

Our organization presented itself as a perfect pyramid — with information and advice flowing up to me, and decisions flowing down. We were “gripping” the problem and “dominating” the agenda in our “mission” to “end global poverty.”

The myths we spun were astonishing. We sat through conferences on international development, listening to expert after expert saying that the answer to all this is to focus on “best practices,” “capacity building,” and “political will.” This sounded good but was actually profoundly offensive. It translated to saying “people in this poor country were ignorant, unskilled, and lazy. We’re going to come in with our knowledge, training, and willpower to fix it.” It was and is the fantasy of the Turnaround CEO.

Of course, domestic politicians and philanthropists pose as heroes too. But they are at least forced to engage with some feedback. The schools or clinics they fund in Europe or the U.S. are places where people who they know might go. Local journalists can expose their failures. Citizens, tax-payers, voters, who are not shy about challenging the expertise and performance of the “leaders,” can burst their bubble.

But none of this is true in international development. Imagine being someone in Washington or London or Paris working to “end poverty” in Malawi, the world’s poorest peaceful country. You live on the other side of the planet. You almost never meet the individuals in the villages, in which you are running your programs. Even if you met them you would not speak their language, or understand their culture or the details of their daily lives. And there is no feedback. These people don’t vote for you, and the global media rarely reports on your work.

You can, therefore, convince yourself of all kinds of myths about yourself and your programs. And if the villagers tried to point out how bad the school you have funded is, or just how much of your money has been wasted, you would be offended, and tempted to ignore them. After all, it’s not their money, it’s yours. It’s “charity.”

And this is why our international development programs are so often ludicrously wasteful and grotesquely ineffectual. I visited aid programs in which $38,000 out of the $40,000 set aside for bringing sanitation to a school, was spent on program design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation, and only $2,000 ended up buying a couple of basic latrines and some red plastic buckets.

And this was not just true of the UK’s programs. A congressional watchdog agency analysed a $280 million U.S. program in the developing world, and could only find 55 beneficiaries.

Philanthropists also fund many wasteful vanity projects such as The Play Pump: an impractical investment in which African children were supposed to pump water through playing on a carousel, and which resulted in their exhausted mothers having to operate the playground equipment to drink.

The whole development industry is staffed — and I was one of them — by people who are praised for our “service” by friends and family, as though we were saints saving the world.

The macro trends confirm this. There were about 170 million people living in extreme poverty in Africa in 1980. Forty years later — after governments, international agencies, and nonprofits spent a trillion dollars — there are 430 million unable to meet their most basic needs. And yet, the whole development industry is staffed — and I was one of them — by people who are praised for our “service” by friends and family, as though we were saints saving the world.

I blame our addiction to the slogan “give a man a fish, he eats for a day; teach a man to fish, he eats for a lifetime” — a magical idea that we the outsiders were “fishing” experts who could somehow do something, one time, which would transform poor people for the rest of their lives.

But a visit to Rwanda with GiveDirectly, a nonprofit, convinced me we have got this exactly the wrong way up. GiveDirectly did the opposite. Instead of turning up with some complex idea, developed thousands of miles away, to change everyone’s life, they simply give every family in a poor village about $1,000 and let them spend how they see fit. Not a loan. One-time cash with no strings attached.

At first blush, it sounded like a terrible idea. We were meant to be “teaching a man to fish,” and handing out cash sounded like a giant fish-giving operation. But I saw on my visit (and you can see for yourself), it works shockingly well. A year and half later, the community was radically transformed. From just a third owning a cow to two thirds. From half of people with electricity to 80%. New businesses had sprung up. Everyone had government health insurance. The countryside shimmered with new, iron roofs and beneath them were well-fed families sleeping on their first ever mattresses.

So why does giving cash work so well? There are four factors that determine if a development project succeeds or fails:

- Is it appropriate for the unique context? Not cookie-cutter or universalist.

- Is it adjusted flexibly to meet individual needs and priorities? Not one-size-fits-all.

- Is it giving the recipients freedom, control, and dignity? Not deciding for them.

- Is it efficient and cost-effective? No excessive overheads.

The only aid model I’ve seen do all four is unconditional cash transfers.

It is a lesson in radical humility. Instead of seeing ourselves as heroic CEOs, we are trusting other people. The decisions are totally decentralized, disaggregated, and devolved to the level of the individual in the poorest household. Each family uses the money creatively to respond to opportunities and investments made by all the other families in their village. Some will pool funds to bring in a water pipe. Others will form a round-robin savings circle. Some buy cows, so some will learn veterinary medicine. This synergy creates a fly-wheel that can grow the local economy by a factor of 2.5 times the money put in.

When are we — in companies or in government — behaving as though some superhero in the centre has the knowledge and power to fix everyone else’s life?

With cash in hand, the recipient and their community become the expert and the leader, finally given the dignity to choose for themselves.

I came to direct giving as an effective tool for lifting people out of poverty, but found it holds a profound lesson in leadership. It turns radically against the single heroics of the individual, inverting our entire mental model of what leadership means to encompass a whole network and community.

And it leaves with me two larger questions that apply to all our lives. When are we — in companies or in government — behaving as though some superhero in the centre has the knowledge and power to fix everyone else’s life? And what would a radical inversion look like? Instead of tinkering with program designs and feedback mechanisms, what if you gave power and decision-making to the most local level — your industry’s form of “direct giving”?

Here the moral lesson of humility is also the route to a more effective program and — in international development — a more just world.