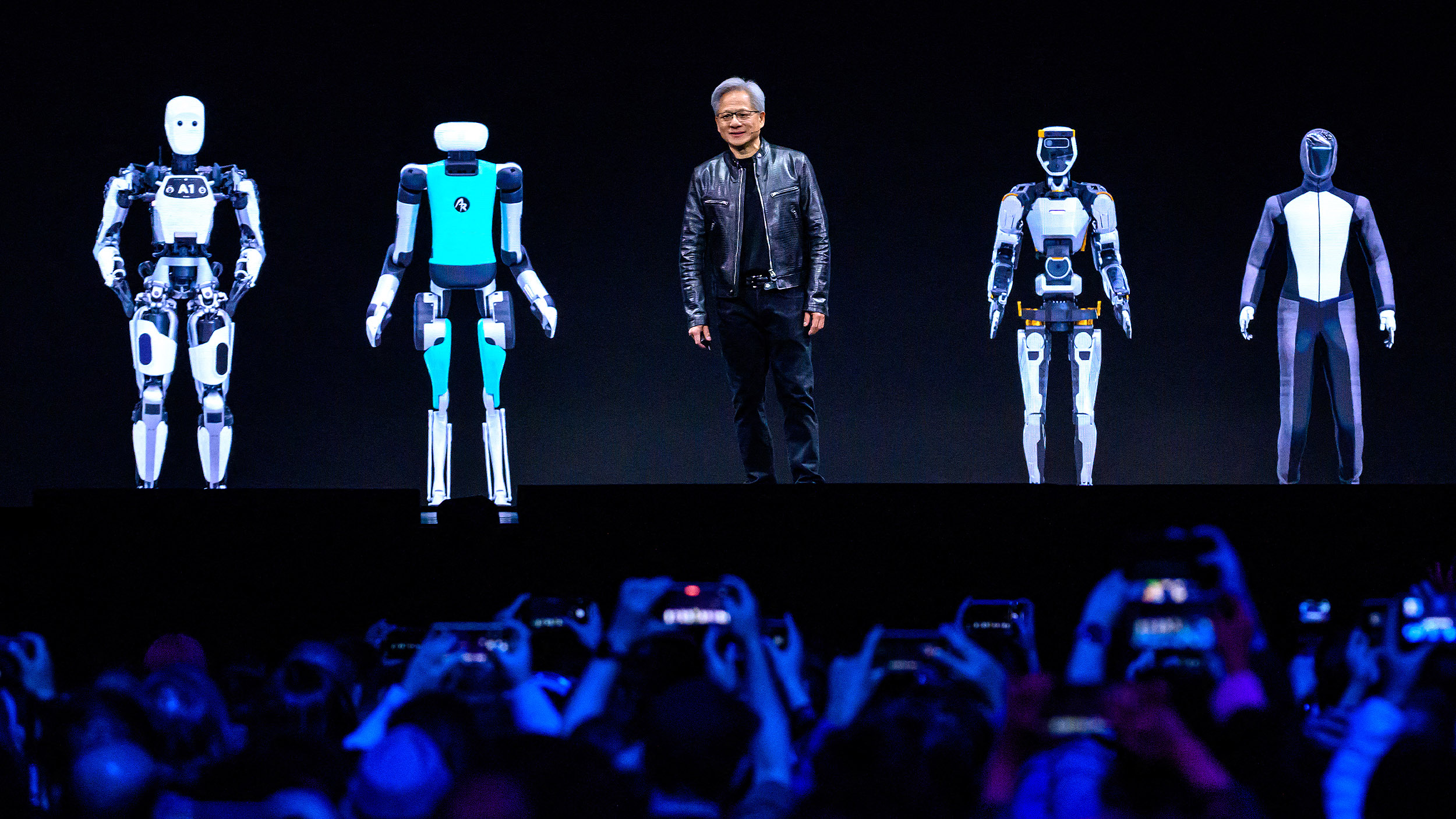

The trillion-dollar answer to AI’s biggest question

- Main Story: Autonomous vehicles could provide a crucial revenue solution for AI’s looming bubble.

- In times of technological sea change, it can pay to think in probabilities, and play the long game.

- Also among this week’s stories: The downside of efficiency and optimization, Apple’s beautiful packaging, and the history of oil.

In June, Sequoia Capital published an essay proclaiming the AI bubble is “reaching a tipping point.” The essay went viral, in part, because it asked a rather pointed and timely question: with hundreds of billions of dollars spent on AI, where is all the revenue going to come from?

This week, my colleague Dan Crowley presented a very clear (hypothetical) answer to this question: autonomous vehicles could usher in a “Cambrian era” of new revenue streams, amounting to many trillions of dollars over the long-term. In particular, Dan highlights three distinct revenue streams that could be unlocked by self-driving cars — a future that may be closer than many people believe.

“This is a very exciting moment,” Dan writes. “Rarely in markets do we see opportunities where two investors, faced with the same information, can draw two wildly different conclusions. It’s also very clear that one of us is right — and one is wrong.” He continues:

Key quote: “As investors, it’s good to be skeptical. And we agree with Sequoia that it’s smart to be realistic about the gap between what’s being spent on AI — and the revenue being generated, especially in the short-term. But there’s a thin line between skepticism and outright pessimism. In times of technological sea change, we feel one needs to broaden the aperture, think in probabilities, and play the long game. It’s not about where the technology is today; it’s about where it could be in a few years from now. We subscribe to the William Gibson philosophy: ‘The future is already here – it’s just not very evenly distributed.'”

The timeless value of inefficiency

A few months ago, I wrote an essay for Fast Company with a somewhat contrarian take: AI will struggle to come up with truly creative ideas because so much of actual creativity is born out of human mistakes. I offered the example of Alexander Fleming, the Scottish scientist who developed penicillin — but only because of a lab accident.

In an essay published this week, Rory Sutherland advances this concept a step further. Rory — an advertising executive and prolific writer — makes the case that more efficient systems don’t always benefit us. In fact, he argues, they may make us less productive — and less creative in our thinking.

“The general assumption driven by these optimization models is always that faster is better,” Rory writes. “I think there are things we need to deliberately and consciously slow down for our own sanity and for our own productivity. If we don’t ask that question about what those things are, I think we’ll get things terribly, terribly wrong.”

Key quote: “Now, here’s my point. Most of you, if you were students, wrote essays or something like that as undergraduates, right? Fairly confident to say that nobody’s actually kept them? Nobody re-reads them. In fact, the essays you wrote are totally worthless. But the value wasn’t in the essay. What’s valuable is the effort you had to put in to produce the essay. Now, what AI essays do is they shortcut from the request to the delivery of the finished good and bypass the very part of the journey which is actually valuable — the time and effort you invest in constructing the essay in the first place.”

A few more links I enjoyed:

The Lesson of Obsession: Robert Caro and Mr. Beast – via Frederik Gieschen

Key quote: “At first glance, Caro and Donaldson couldn’t seem more different: thousand-page biographies vs. a YouTube channel whose most popular video is ‘$456,000 Squid Game In Real Life!’ However, both owe their success to an intense passion and awe-inspiring obsession with mastering their craft. Where they differ is not just their medium but their goal — and this is where I found a foundational lesson about creative work.”

Do It Your Way – via Morgan Housel

Key quote: “How you invest might cause me to lose sleep, and how I invest might prevent you from looking at yourself in the mirror tomorrow. Isn’t that OK? Isn’t it far better to just accept that we’re different rather than arguing over which one of us is right or wrong? And wouldn’t it be dangerous if you became persuaded to invest like me even if it’s wrong for your personality and skill set?”

Psychology of Apple Packaging – via Trung Phan

Key quote: “The affinity we have for Apple boxes is not random. It comes from the company’s deep understanding of human psychology. As Walter Isaacson wrote in his Steve Jobs biography, beautiful packaging is one of Apple’s key marketing principles. These principles were written by Mike Markkula, Apple’s original investor and second CEO.”

Daniel Yergin – Oil Explains the Entire 20th Century – via Dwarkesh Patel

Key quote: “Unless you understand the history of oil, you cannot understand the rise of America, WW1, WW2, secular stagnation, the Middle East, Ukraine, how Xi and Putin think, and basically anything else that’s happened since 1860. It was a great honor to interview Daniel Yergin, the Pulitzer Prize winning author of The Prize — the best history of oil ever written (which makes it the best history of the 20th century ever written)”

From the archives:

The Psychology of Human Misjudgment – via Charlie Munger (2005)

Key quote: “The extreme success of the ants also fascinated me — how a few behavioral algorithms caused such extreme evolutionary success grounded in extremes of cooperation within the breeding colony and, almost always, extremes of lethal hostility toward ants outside the breeding colony, even ants of the same species.”