How the neuroplastic “Tetris Effect” can unblock work-life obstacles

- The Tetris Effect occurs when a task you do for a prolonged period of time starts to rewire your thinking and perception.

- It is caused by neuroplasticity, where the brain adapts and forms new connections based on behavior.

- Here we look at ways to harness the Tetris Effect in our work lives.

Sophie arrived late to the Game of Thrones craze. She held off for a while because she “doesn’t do dragons,” but she watched the first episode, and now she’s hooked. She watched the entire first season in a single lounge-lizard day. As she gets into bed that night and goes to sleep, she sees dragons. She sees swords and medieval armor. Her imagination conjures up, jumbles about, and relives nine hours of Westeros. Her waking mind absorbs, and her sleeping mind repeats.

John has watched a lot of Louis Theroux. For John, no other interviewer is half as interesting as the awkward, strange-looking Brit. John has learned about the niche, eccentric fringes of society, and he loves how Louis gets people to open up. But John’s friends have noticed something odd. John has started talking like Louis. His intonation and his beat are all Theroux. He even pauses more often and seems to embrace an interrogative conversation. He doesn’t know it, but John is being someone else.

Sophie and John are two examples of what’s called the “Tetris Effect.” It’s when you saturate yourself so much with a task that the task rewires you in some way. If you do something for a prolonged and intense period of time, then it takes over not only your dreams but your entire way of thinking.

How does the Tetris Effect work, and how can we learn to harness it in our everyday lives?

Blocks everywhere

The Tetris Effect gets its name from a phenomenon experienced by those who played a lot of the game Tetris in the 1980s. Tetris works by moving and rotating shapes into position to form a neat line. When the line is complete, the line vanishes, and the game goes on. What people noticed was that when they played the game for hours and hours on end, something changed in their mindset. When players walked away from their consoles, they started to see the world in terms of Tetris. They were inescapably aware of square windows and would obsessively stare at rectangular doors. People started to rotate buildings in their heads or try to line up cereal boxes at the store. Tetris rewired how they saw the world. Suddenly, the world was full of Tetris blocks.

It’s all to do with neuroplasticity. Your brain is constantly adapting to the world. It’s learning about — and molding itself to — all the many environments you present it with. Up until the very second you die, your brain will be forming new neuronal connections. And the way that your brain “learns” is through behavior. In other words, if you change your behavior, you change your brain. So, if you spend a lot of your time doing one thing, such as playing Tetris or watching Louis Theroux, your brain will adapt to that stimulus. It will conclude, “This thing is clearly very important; let’s do more of it.”

Seeing Tetris blocks everywhere might not be a Marvel-level superpower. In fact, some might see it as a kind of hell. But the important thing about the Tetris Effect is that not only does the brain learn that Tetris is important, but it becomes really good at it. Obsessive Tetris players develop new neural pathways and cognitive abilities, which make them Tetris professionals. Excellence, in anything, is a multi-hour, multi-day habit.

Putting the shapes together

The Tetris Effect can be both good and bad news. Good habits make us more productive, relaxed, and happier. But bad ones can make us exactly the opposite. How, then, are we to get the most from the phenomenon? Here are many ways in which we could apply the Tetris Effect.

Be thankful. The author and speaker Shawn Achor once showed how the Tetris Effect could be harnessed to give us a more positive mindset. He argued that when we are repeatedly thankful for things, then we start to see the good in life more. The same is true for work. If we consciously tell other people how much we appreciate their work, then, after a while, we’ll start to appreciate everything everyone does more. If we start to tell other people how much we like our job or make a list of all the good things about being there, then we’re more likely to be positive about things. Of course, there is such a thing as toxic positivity: if something is broken or wrong, don’t sugarcoat it. But growing and reinforcing a thankful attitude will, in the end, make you happier.

Switch your phone to work mode. It will come as no surprise that phones are addictive. Both your phone itself and the apps that populate it are deliberately designed to keep you coming back for more; they’re a bottomless, silicon-lined well of dopamine. Phones can be incredibly productive, and most modern workplaces need, or at least are easier with, a phone. But the urge to constantly check and pick up the phone is hugely disruptive. It’s disruptive, not only in terms of the time lost, but it’s estimated that it takes around 20 minutes to regain your focus. That constant desire to look over at your phone and that pathological need to open a notification are born of habit. They’re the negative application of the Tetris Effect. It’s often not practical or even helpful to go “cold turkey” with your phone, and not all screens are bad. Instead, try a work mode where only certain work apps will notify you. Or, designate a time of the day for a certain screen, such as an hour after lunch, to deal with work-related phone notifications.

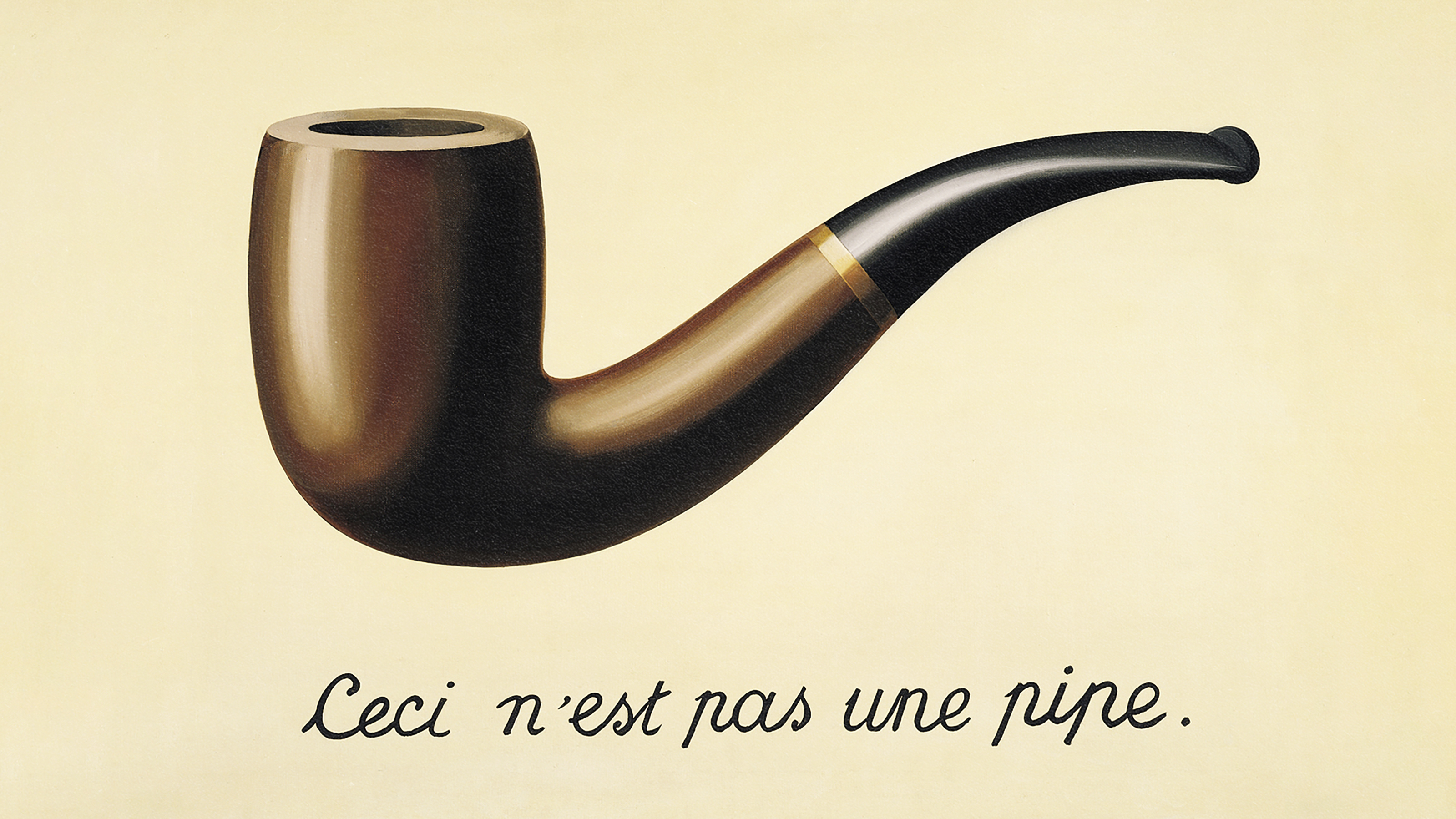

Stop othering people. Work can often be a game (albeit less enjoyable at times). It involves a certain performance or role-playing. There are quests and rewards. Like Tetris, a great many parts need to be moved around if they’re to work. The problem, though, is that when you spend too much time with a “work mindset,” you start to see other people as just shapes to be moved. Spending too long in an office space and nestled in a work structure, you don’t see Fran or Bob; you see “that accounts lady” or “the IT guy.” You lose their humanity. On Big Think+, the economist and bestselling author, Douglas Rushkoff, borrows a little bit of French existentialism to refer to this as “othering.” This is when we present other people not as fully-realized human beings with their own mental and emotional lives. Instead, we see them as pawns to move or shapes to slot here and there. Rushkoff’s advice is simple and powerful. When dealing with colleagues, “meet them, engage with them, listen to them, really hear them like a human.”