The “McNamara fallacy”: When data leads to the worst decision

- The McNamara fallacy is what occurs when decision-makers rely solely on quantitative metrics while ignoring qualitative factors.

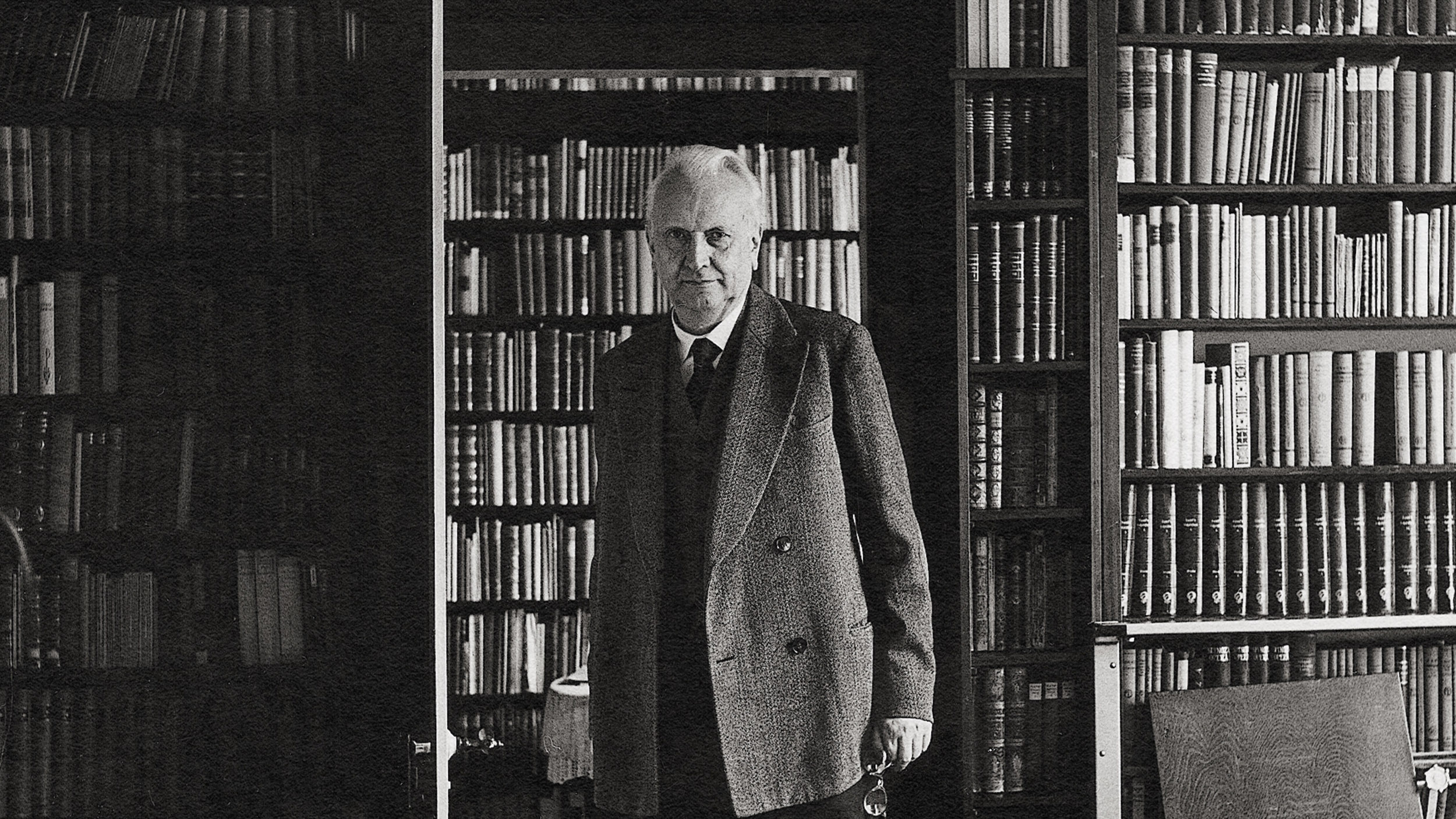

- The fallacy is named after Robert McNamara, the U.S. Secretary of Defense during the Vietnam War, where his over-reliance on measurable data led to several misguided strategies.

- Here we look at three work-life situations where data might mislead us as much as help us.

In 2014, I took a weekend break to York. York is a lovely city in the north of the UK, with an ancient cathedral, quaint cobbled roads, and an interactive Viking experience. It was a great weekend. But when I first got off the train there, I was hungry and disoriented. I’ve never been much of a trip planner — a habit that worsened with the invention of iPhone apps.

So, I got my phone out and used TripAdvisor to search “Best places to get lunch in York.” Up popped a variety, but leading the list was a curiously named restaurant called Skewers. Skewers had a variety of professional-quality photos of mouth-watering food. After a short walk, I found myself outside Skewers. It turns out that Skewers is not a restaurant but a kebab van. It looked like a nice kebab van, populated by two friendly Turkish men, but it wasn’t quite the holiday lunch I had in mind. I was looking for something on a plate and with a knife and fork. Not something eaten from a polystyrene pot.

The problem was that Skewers was an incredibly popular kebab van for the many students at York University. As pickled 19-year-olds staggered out of a nightclub at 3 a.m. craving some greasy takeaway, Skewers was there to help. And as these students scoffed and slobbered their way home, they tapped 5-stars to Skewers. And hence, Skewers became the “best restaurant” in York.

The story of Skewers is an example of the McNamara fallacy, and learning about it can help us all (especially the underprepared tourists among us).

The McNamara fallacy

The McNamara fallacy is what occurs when decision-makers rely solely on quantitative metrics while ignoring qualitative factors. In other words, it’s when you look at raw numbers rather than the nuances that matter in the decision-making process. In my case, the 2014 version of the TripAdvisor app (it’s much better now) promoted Skewers to #1 on the basis of votes rather than other options. The fallacy is named after Robert McNamara, the U.S. Secretary of Defense during the Vietnam War, where his over-reliance on measurable data led to several misguided strategies where considering certain human and contextual elements would have been successful.

The McNamara fallacy is not saying that using data is bad or that collecting as much information as you can is wasted time. It’s saying that fixating only on numbers blinds us to the rich stories and subtle details that truly shape experiences, resulting in choices that miss the heart and soul of the situation. If we spend too long looking at spreadsheets and data points, we forget to look around.

There is a certain kind of person who clings so aggressively to data that they wilfully refuse to entertain any decision that goes beyond what that data can prove. But just because something hasn’t or can’t be measured doesn’t mean it has no worth. For example, it’s not uncommon for someone to deeply love a book that has few or no reviews on Goodreads. It’s possible to enjoy a restaurant or a movie in spite of what others say. Data is a great starting point, and a great many idiotic and dangerous things are done when we ignore data, but it doesn’t always make for the best decisions.

Applying the McNamara fallacy

Dig into the details. In many companies, employee performance is measured solely by quantitative metrics like sales numbers or the number of tasks completed. While these figures provide some insight, often the important information is buried in the details. Let’s imagine two people, Jane and Jack, who need to bring in a client. Last year, Jack secured 20 and Jane 15. Good job, team! But, behind the numbers, there’s more to be seen. Jack’s clients really didn’t like him. He had a sleazy, insensitive manner that was off-putting. Within a year, most of his clients had left. Jane, on the other hand, wooed and won her clients by dint of personality. She cared about the person she met. Her clients all stayed around. So, who is the better employee?

Consider the root causes. Businesses frequently rely on customer satisfaction scores (CSAT) or Net Promoter Scores (NPS) to gauge their success. But if you focus exclusively on the numbers, you can often overlook the underlying reasons behind them. A company might boast high satisfaction scores, yet the feedback could reveal recurring issues like poor customer service or product flaws. Conversely, a product might score low satisfaction scores but contain information that would be invaluable for making a different product. By fixating on improving the score itself rather than addressing the root causes, companies may miss opportunities to genuinely enhance the customer experience. Over on Big Think+, Ken Langone, the Co-Founder of Home Depot, says the best way to understand customers is to “engage them in the discussion.” And Langone has some great tips on how to do that well.

Pick up the phone. When your job is to organize a training day or an in-house development program, you will quickly notice a problem: the feedback literature from similar, previous initiatives all looks the same. The blurbs might vary a bit, and the designs will differ in shade and cut, but they will all feature the same parade of glowing reviews and effusive testimonials. So how are you to actually tell the difference? How are you to make a decision? Pick up the phone and talk to the companies or people who experienced those programs. Many studies show that you will often find out more about something in a five-minute conversation than in five weeks of email exchange.