Defamiliarization: How “ostranenie” can redefine life, art, and business

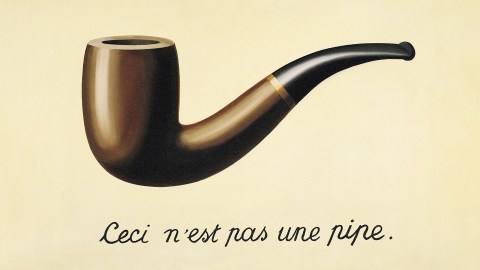

- Ostranenie — or “defamiliarization” — is a term from the philosophy of art.

- Many successful companies, including Cirque du Soleil and Apple, have used ostranenie to great effect.

- Ostranenie is not the same as “pivoting” — it’s a way of seeing.

Nathan Pyle and his wife had invited some guests to their house. As the day for dinner came around, the couple spent hours tidying away all the things scattered about. They made sure every last vestige of clutter was hidden away in cupboards, wardrobes, and drawers. At no point should their guests see a house as it’s lived in. They must see it tidy. Pyle found the entire experience peculiar. He found it funny. And so, he drew a comic making light of the whole thing and put it on social media.

“Your home is beautiful,” his guests say.

“Thank you — we own things, but we have hidden them,” they reply.

That was in 2019. Today, Pyle’s Strange Planet has nine million followers on social media. He has a series of books, a clothing line, and an Apple+ TV show. What Pyle does well, and why he’s so popular, is that he presents common, everyday situations in a comically unfamiliar way. His characters — mostly aliens — narrate normal human behaviors in a way that makes you think, “Wow, that is weird.” This technique has a particular name in aesthetics: ostranenie (aw-STRAH-nuh-nee). Not only is it a neat philosophical idea, but it can also be a transformative business strategy.

The familiar made new again

Ostranenie is usually translated as “defamiliarization.” It’s when you take something that you’re used to and look at it from a completely new angle. You take the old and make it appear new. You look at things as if for the first time. We owe the term to the Russian literary critic, Viktor Shklovsky, who read and admired it in Leo Tolstoy’s books. One of those books, Kholstomer, is a story almost entirely narrated from the perspective of a horse. Take, for example, this passage:

“I was quite in the dark as to what they meant by the words ‘his colt’… At that time I could not at all understand what they meant by speaking of me as being a man’s property. The words ‘my horse’ applied to me, a live horse, seemed to me as strange as to say ‘my land,’ ‘my air,’ or ‘my water.'”

Here, Tolstoy has taken a familiar idea — owning animals — and made us look at it from an entirely new point of view. We are meant to examine it as if for the first time. This kind of defamiliarization is common in the arts. It’s in Tolstoy, yes, but it also underpins Seven of Nine in Star Trek (human as alien) and Barbie’s Barbieland (stereotypical toy as satirical vehicle). For Shklovsky, defamiliarization is the hallmark of any good art. It can also be the hallmark of a wildly successful business.

A circus without animals

There has only ever been one way to make money: you sell something that someone wants. There are two ways to do this. Either you offer a better product than all the others, or you present a product that meets that want in a new way. Let’s take an example.

By the 1980s, the circus industry was in decline. Its business model was tired. What had the circus to offer? Why would anyone go? We can imagine a dialogue from Pyle’s Strange Planet:

“Darling, would you like to see some animals being tortured by people in Halloween outfits?”

“Can’t we watch that on TV?”

“Oh no, this way we get to sit in cramped stalls and pay for it!”

When Guy Laliberté and Gilles Ste-Croix founded the troupe that would become Cirque du Soleil, they applied this kind of ostranenie. They defamiliarized the experience. So, they cut out animal acts altogether. They presented a spectacle that fused ballet, opera, acrobatics, and storytelling. They began as circus performers, but, as Ste-Croix put it, “We became a musical, theatrical event with circus performers.”

Thanks to ostranenie and this “first principles” approach, Cirque du Soleil is a billion-dollar company. They have performed for roughly 400 million people in 86 countries (as well as the resident shows in Las Vegas). In just 20 years, Cirque du Soleil was earning more than Barnum & Bailey — the once global leaders in the circus industry — could in 100 years.

3 ways to apply ostranenie

Ostranenie is not quite the same as “pivoting,” where you reinvent your business or a product in a new way. It’s more a state of mind or way of seeing. Here’s how you can apply it in your business.

Love the problem. Every business sells a solution to a problem. They are satisfying a want. It’s easy to get swept away in the minutiae of the latest product design, and so we often forget to ask, “What is it we’re actually doing?” Netflix was selling entertainment, not DVDs. Steve Jobs was selling communication, not phones. What problem are you solving, and is this product the best way to solve it?

Bring in outsiders. Engage individuals outside of your industry or even hire consultants who don’t have a background in your field. These people can provide a fresh perspective, free from the biases and habits that industry insiders might have. Outsiders can challenge established norms and ask seemingly naive questions that can lead to breakthrough insights. In other words, you want to hire Tolstoy’s horse.

Embrace your inner alien. If you’re not inclined to hire an outsider, you can just as easily channel your inner alien. Imagine you are visiting extraterrestrials and trying to explain to them what you are doing. Imagine how they might respond. At your next meeting, take a leaf from the Nathan Pyle playbook: Get everyone to explain their job, task, or product in Strange Planet language. By looking at your product or service without preconceptions, you might see opportunities or issues that you’ve overlooked.