How to harness the power of randomness to optimize your decision-making

- Randomness can be used as a solution to “analysis paralysis” when confronted with an excess of choice.

- Offering consumers fewer choices rather than more seems counterintuitive, but it can be beneficial.

- For instance, research has shown that less choice can result in markedly better sales.

In February 2014, a strike on the London Underground Network caused significant disruption to hundreds of thousands of commuters, forcing them to find alternative routes to work. A team of economists from Oxford, Cambridge, and the International Monetary Fund analyzed thousands of commuter journeys before, during, and after the strike. They found that up to 5% of the people disrupted from their habitual commutes ended up adopting these alternative routes permanently after the strike had finished. Their results suggested that a significant proportion of commuters had failed, of their own volition, to tweak their journey to work to find the optimal commute. They’d chosen instead to settle for a passable trip which avoided the risk of the one or two extended commutes that might result from experimenting with their journeys. The economists predicted that the randomizing factor of the strike, forcing some commuters to find better routes, would have a net economic benefit in the long term — the time saved by the 1 in 20 commuters breaking the habit outweighing time lost by all commuters during the strike.

Employing randomness to optimize a process is not a new idea. For hundreds of years, the Naskapi people of eastern Canada have been using a randomized strategy to help them hunt. Their direction-choosing ceremony involves burning the bones of previously caught caribou and using the random scorch marks which appear to determine the direction for the next hunt. Divesting the decision to an essentially random process circumvents the inevitable repetitiveness of human-made decisions. This reduces both the likelihood of depleting the prey in a particular region of the forest and the probability of the hunted animals learning where humans like to hunt and deliberately avoiding those areas. To mathematicians, using randomness in this way, to avoid predictability, is known as a “mixed strategy.”

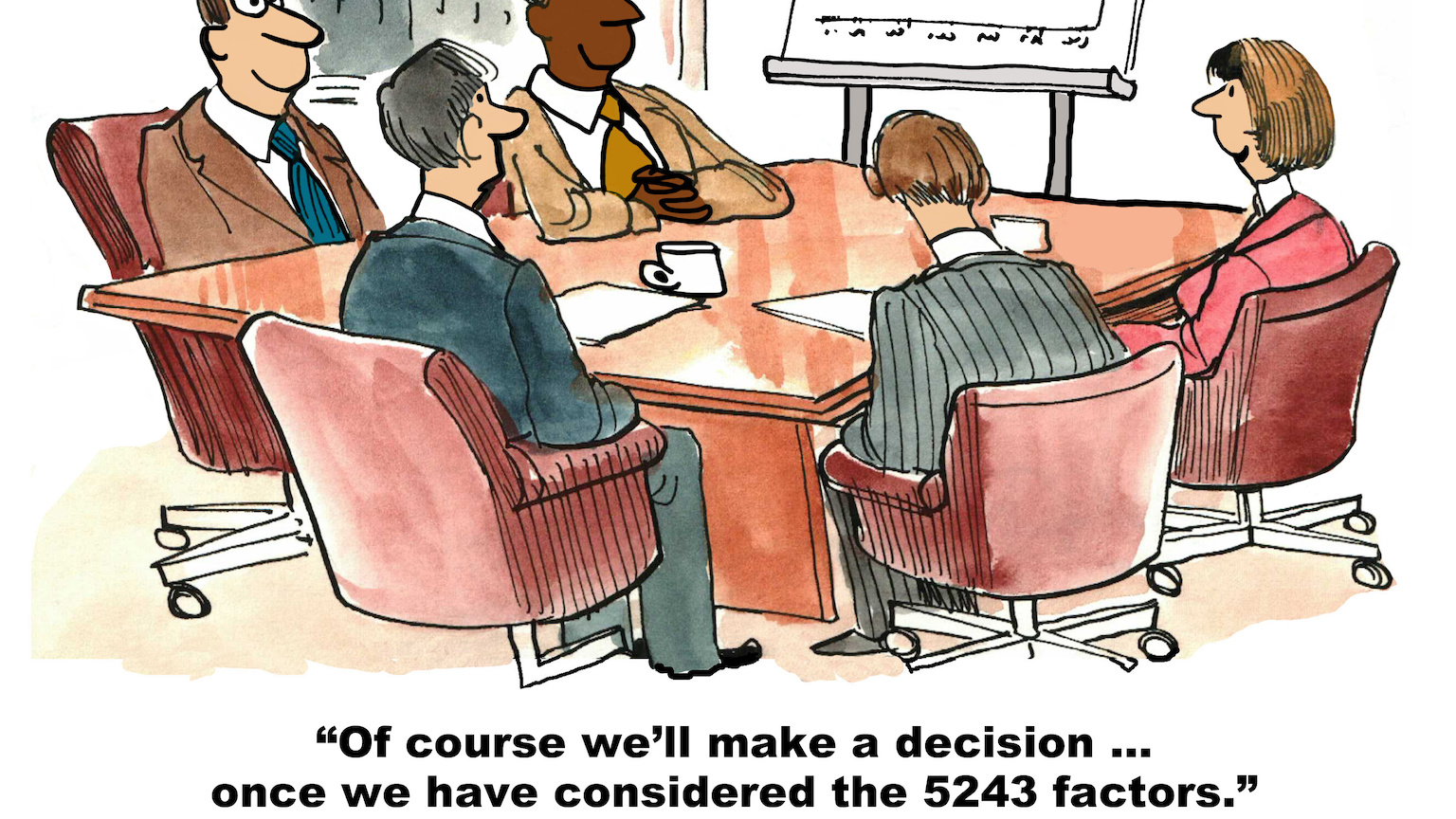

Another way in which randomness can help us to make difficult decisions about the future is in the avoidance of “analysis paralysis.” If you’re anything like me, then you might experience a mild form of this phenomenon when choosing what to order from an extensive menu. Should you go for the risotto or the burger, the steak or the pasta? I am so indecisive that the waiter often has to come back a few minutes after taking everyone else’s order to finally hear my choice. All the choices seem good, but by trying to ensure I choose the absolute best option, I am running the risk of missing out altogether.

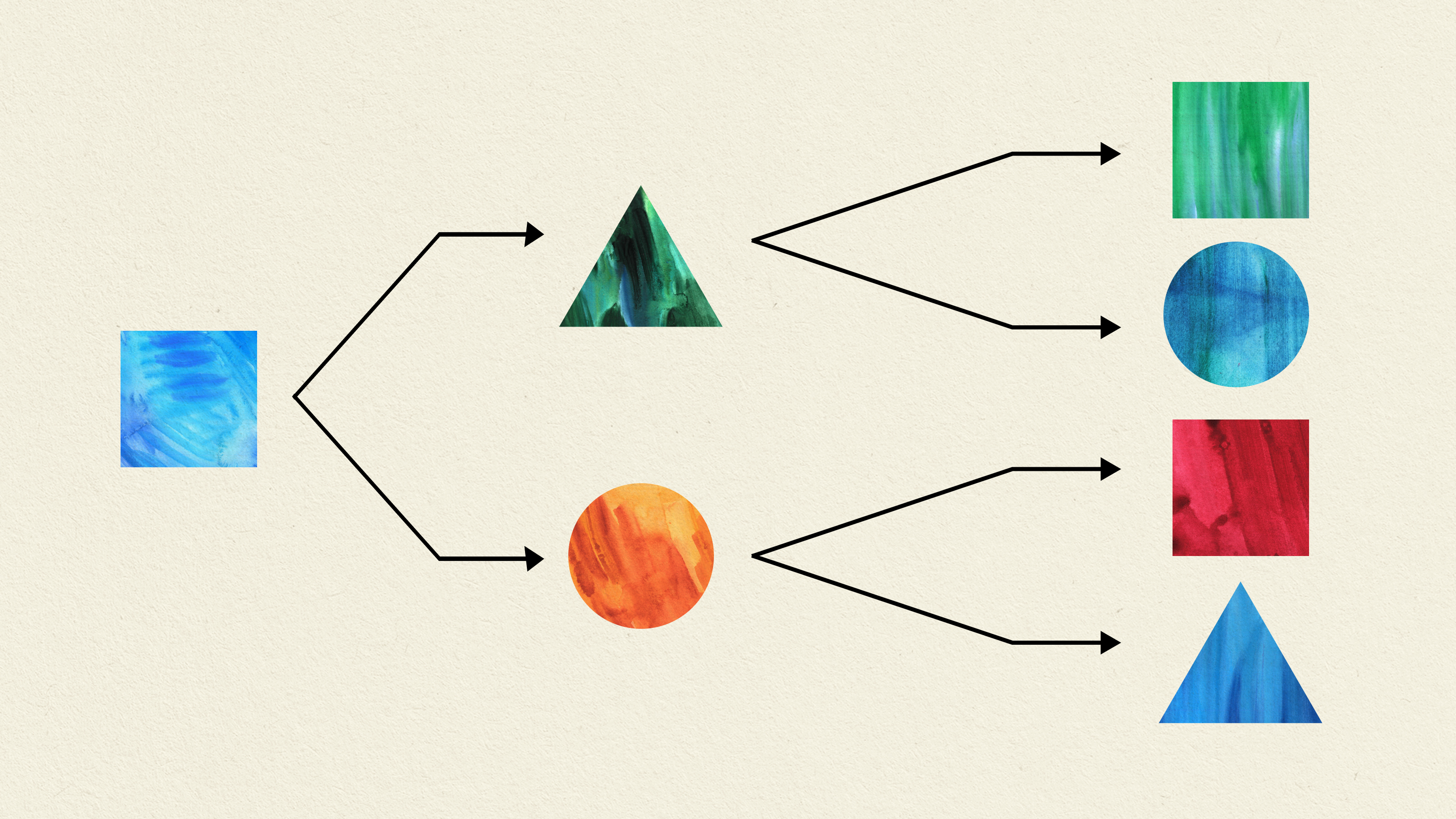

Restaurants are certainly not the only places in our modern world in which analysis paralysis rears its head. In almost all areas of life, from the everyday choices about the groceries we buy or the clothes we wear, to the big decisions concerning where we should live or whom we should date, the internet now delivers an unprecedented amount of choice. Even before the internet brought these decisions directly into our homes and the phones in the palms of our hands, choice had long been seen as the driving force of capitalism. The ability of consumers to choose between competing providers of products and services dictates which businesses thrive and which bite the dust — or so the long-held mantra goes. The competitive environment engendered by consumers’ free choice supposedly drives innovation and efficiency, delivering a better overall consumer experience.

However, more recent theorists have suggested that increased choice can induce a range of anxieties in consumers — from the fear of missing out (FOMO) on a better opportunity, to loss of presence in a chosen activity (thinking, “Why am I doing this when I could have been doing something else?”) and regret from choosing poorly. The raised expectations presented by a broad range of choices can lead some consumers to feel that no experience is truly satisfactory and others to experience analysis paralysis. That more options provide an inferior consumer experience and make potential customers less likely to complete a purchase is a hypothesis known as the paradox of choice.

Just 3% of those who’d been presented with two dozen jams ended up buying a jar, compared to an enormous 30% of those who’d tasted from the six jams in the restricted range.

In 2000, researchers from Columbia and Stanford Universities set out to explore exactly this hypothesis. On two consecutive Sundays, they set up a tasting booth at a high-end grocery store in Menlo Park, California. On the first Sunday, the stall was stocked with 24 different flavors of jam, which customers were allowed to taste test. On the second Sunday, the number of samples was reduced to just six. The display with the larger range was successful at attracting 60% of passers-by, while the smaller range attracted only 40%. However, on average, the customers tried the same number of jams (just two) irrespective of the choice on offer. By far the most striking aspect of consumer behavior seemingly revealed by the study came when the customers were followed up to find out how many of them had actually purchased a jar of jam. Just 3% of those who’d been presented with two dozen jams ended up buying a jar, compared to an enormous 30% of those who’d tasted from the six jams in the restricted range. The suggestion was that the excessive choice in the first day’s products left consumers feeling ill informed and indecisive when making a purchasing choice.