Go grudge-free: Use the “Weil method” to deal with insults

- Workplaces are stressful and exhausting environments, and when you jam people together, there’s inevitably going to be conflict.

- Our tendancy to negativity bias means we dwell on insult and injury, and we bear grudges easily.

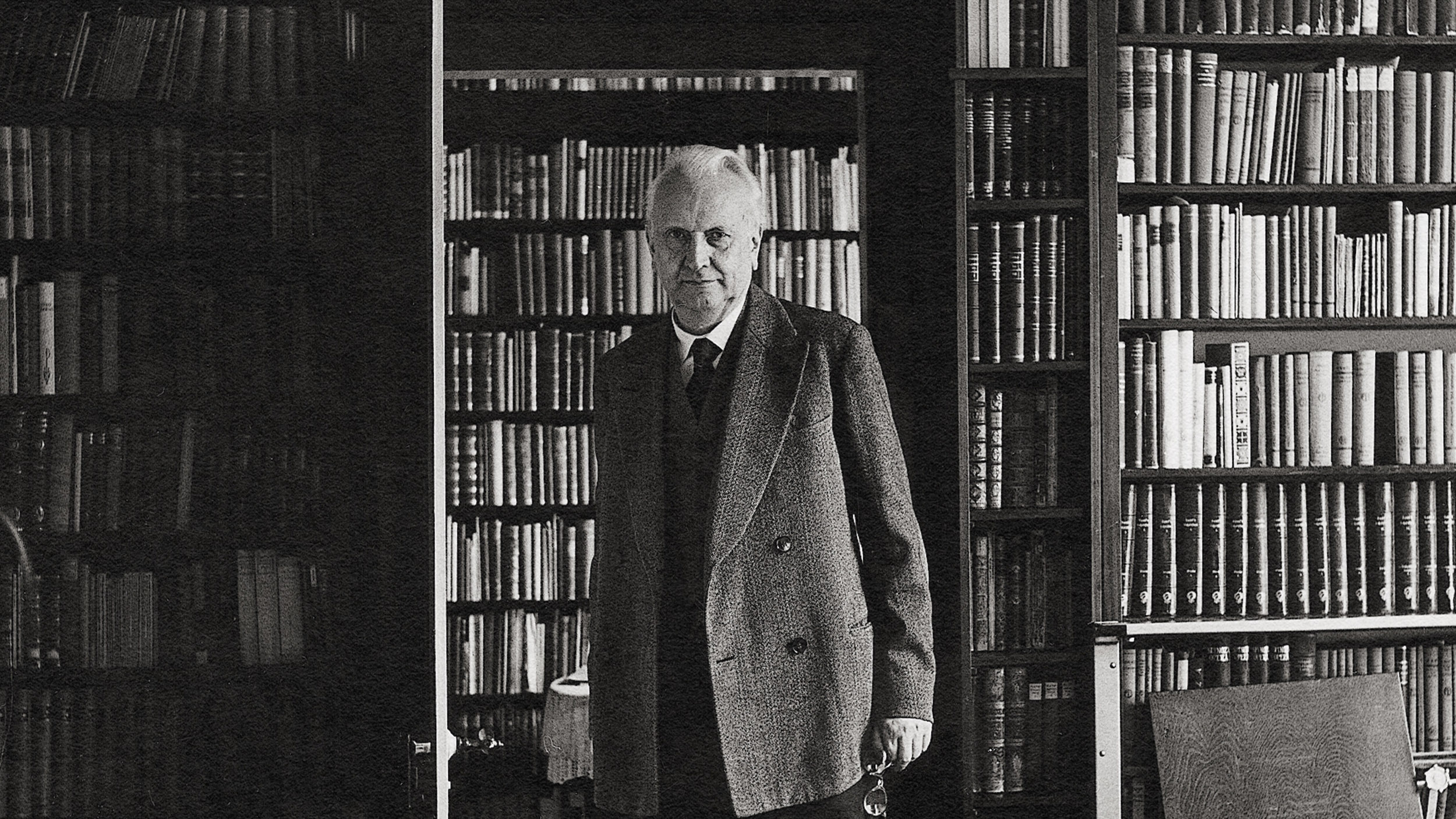

- Philosopher Simone Weil suggests a way to reframe the insult as a debt that is in your power to forgive.

Work can often be stressful. It can be exhausting. And so, when you jam exhausted and stressed people into a room or with a three-day deadline, you can pretty much expect there’s going to be some kind of carnage. People will snap and bite. They’ll hiss and sneer. There will be blood.

A large proportion of society will have some story of workplace conflict. It might be a small, passive-aggressive incident that makes Zoom meetings a bit frosty, or it might be a full-throated screaming match at last year’s office party. But, if you work in a company any bigger than a handful, you will likely have some kind of drama to seethe about.

And this drags us down. Humans often tend towards a negativity bias, where we dwell on the negative elements of life far more than the positive ones. I could give you ten glowing pieces of praise about some work you did, but if I mentioned I thought it could have been a bit shorter, that’s the bit you’ll remember. So, too, with arguments. We remember the harsh words and icy scowls. We relive the moment and obsess over the insults.

So how are we to deal with workplace conflict? How can we forgive a wrong done more broadly? The French philosopher Simone Weil has some advice to give.

A stolen part to fill a hole

A broken glass is dangerous. Its shards can cut or mutilate the hands that were holding it seconds ago. Likewise, a broken human can be a dangerous thing. When we’re in pain or when we’re lost, we can often lash out. We can hurt everyone and anyone, and we often hurt ourselves.

For Simone Weil, when we hurt other people, it’s a sign that we’re lacking something important in our lives. As Weil put it, “To harm a person is to receive something from him. And what have we gained when we have done harm? We’ve gained in importance. We have expanded. We have filled an emptiness in ourselves by creating one in somebody else.”

There is something vampiric about an insult or harm. It takes from the other person what we are missing. When some people are in pain, they want others to hurt too. Misery enjoys company, after all. If we’re missing joy in our lives, we want to steal that joy from others. Because stealing from others is easier than building or fixing it ourselves. So, the first lesson Weil gives us is that if someone at work or in your life has done something unambiguously cruel or insulting, ask yourself what hole is that person trying to fill?

But the second lesson Weil is keen to teach is about letting the insult go. Weil argues that reframing hurt in this way allows us to forgive other people. Suppose that your friend or your partner does something harmful to you. Weil asks us to imagine it as a kind of theft. They have stolen a bit of warmth from you to keep themselves from the cold.

And so, resentment is a kind of debt. We imagine the wrongdoer owes us something. Your colleague needs to buy you a present. Your boss needs to publicly apologize. But forgiveness and healing come in forgiving this debt. We should see hurt as a gift given to somebody in need.

You don’t need to be a saint

Weil was a Christian, and her argument here is very much her version of “turn the other cheek.” It’s a hugely demanding philosophy, but she lived it; Weil gave her entire being over to charity and kindness. She was often sickly and nearly died twice: from working alongside manual laborers; and from fighting fascists in Spain. She gave almost all her income to charity, was always politically active, and died in London, at least partially from a self-imposed hunger strike in solidarity with the occupied territories in World War II. But we do not have to take Weil’s wisdom to such intensely sacrificial degrees. Here are three ways we can apply a bit of Weil to our everyday lives.

What’s this actually about? Most humans don’t actively seek conflict out. It’s a biological imperative to get along with others. Humans are social animals, and the deliberately confrontational are a rare anomaly. So, if someone is cruel or insulting, then most of the time there is something that has forced them to be this way. Weil frames it as an act of theft, and the wisdom here is to ask what they actually want. Are they tired, anxious, or overwhelmed by something else in their life? Do they feel unseen, unheard, or undervalued in some way? When you feel wronged in some way, try to remember the human behind the wrongdoing.

Bury the hatchet. A short horror story: you’re in a team meeting and your manager says, “Okay, we’re going to work in pairs.” You’re paired with Grayson. You hate Grayson. You’ve hated him ever since he jokingly made fun of your novelty desk toys. Now you have to work with him.

What Weil is teaching us here is that this is the moment to let it go. Bury the hatchet. You are carrying with you a great burden and a great resentment at some debt owed you. The issue is no longer with Grayson but with you. Forgiveness is not just a Weilian virtue; it’s a psychological boon. Study after study proven that forgiving wrongdoers reduces stress, depression, anger, anxiety, and improves overall wellbeing. Forgiving makes you happy.

Good conflicts. Of course, not all conflicts are born of insult and rudeness. Not every clash in the workplace is because someone called you a mean name or made fun of you. Sometimes, conflicts are more professional. Sometimes, conflicts can even be useful. Over on Big Think+, the therapist and mediator Bill Eddy shares a series of videos about how to identify conflict, how to navigate conflict, and how to grow from conflict. It’s a trove for anyone struggling under a recurrent conflict or facing one on the near horizon.