How to succeed at the “jagged technological frontier” of AI

- AI anxiety is rising as workers worry technology will make their jobs obsolete.

- While generative AI can do some tasks surprisingly well, it still can’t replace human workers and sometimes even degrades human performance.

- Businesses must empower teams to pilot AI or risk losing their competitive edge.

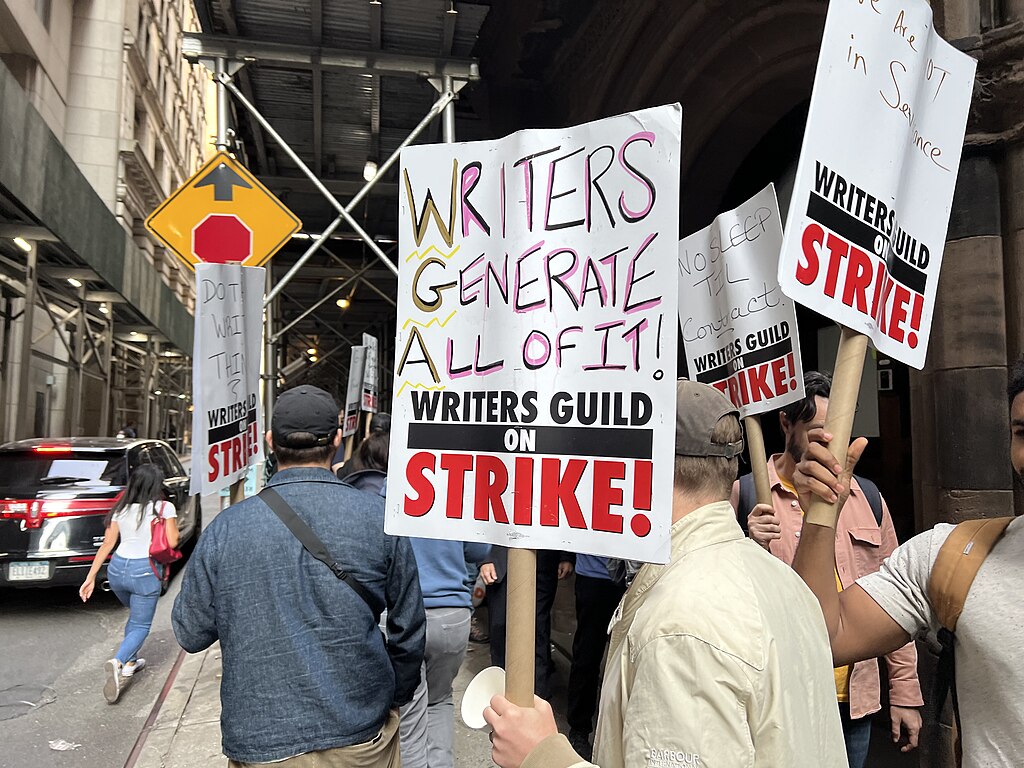

This May, the Writers Guild of America, representing 11,500 screenwriters, went on strike. In some ways, the strike was business as usual. The Guild wanted to renegotiate collective bargaining agreements to reflect seismic shake-ups in the entertainment industry, specifically the shift from broadcast TV to streaming. There was one aspect of the strike, however, that felt eerily like something from a sci-fi script: People picketing against AIs replacing human workers.

These writers are hardly alone in their concern. Several recent surveys have found AI anxiety is rising.

According to the American Psychological Association (APA), close to 40% of workers worry that AI will make some or all their jobs obsolete. Gallup found that 75% of adults believe AI will decrease the number of jobs in the U.S., while 70% don’t believe that businesses will use the technology responsibly. And Pew Research Center data shows unease over the increased use of AI in daily life has risen 14% in the last year.

As one Midwesterner told the APA when asked what employers can do to foster well-being at work: “No more robots and AI crap.”

Are we right to worry? Yes, but the immediate threat isn’t where one might think. The results from a working paper out of Harvard Business School suggest that the real danger isn’t AI itself. It’s business leaders who don’t recognize the challenges of mapping this new technological frontier.

The AI bump

In the study, a team of social scientists led by Fabrizio Dell’Acqua, a research fellow at Harvard Business School, wanted to determine the implications of integrating generative AI into a white-collar workspace. They collaborated with Boston Consulting Group to monitor how 758 consultants performed across 18 tasks for a fictional shoe company.

The consultants were divided among three “conditions.” The first group had no AI access, the second had AI access, and the third had AI access alongside supplemental materials offering guidance on using the technology. The AI of choice was GPT-4, and the tasks were designed to test on-the-job skills such as writing, creativity, analysis, persuasiveness, and problem-solving.

The research team found that the AI-partnered groups completed more tasks faster, and their work was rated to be higher in quality. AI access also appeared to offer a skill-level boost. The consultants who scored worst on pre-study assessments saw their performance jump 43%, on average, with the aid of AI. Even top performers received a bump.

And while this study is currently a working paper — meaning it has yet to be peer-reviewed — other research has shown similar results. In a joint study, researchers from Stanford and MIT found that AI increased productivity by 14%.

Mapping an invisible frontier

But there’s a catch. Dell’Acqua and his team also discovered what they call the “jagged technological frontier.”

Basically, the AI could perform certain tasks well enough to aid human workers and, in some cases, do most of the work itself. Such tasks included analytics, generating new ideas, and penning inspiring memos. Outside of this territory, however, AI was shown to not only be inaccurate and less helpful. It even degraded human performance.

One task asked consultants to provide strategic recommendations based on data from a spreadsheet and interviews with company insiders. However, in a sneaky bit of trickery, the researchers included blindspots in the spreadsheet. Only consultants who compared that data with the interviews could reach the correct conclusions.

On this task, the AI-partnered consultants scored markedly worse, making 19% more mistakes than the control group.

“People really can go on autopilot when using AI, falling asleep at the wheel and failing to notice AI mistakes,” Ethan Mollick, one of the study’s authors and a professor at the Wharton School, writes. “And, like other research, we also found that AI outputs, while of higher quality than that of humans, were also a bit [unoriginal] and same-y.”

That may seem a simple problem to solve. Figure out what tasks AI excels at, outsource that work, and let humans handle the rest. But there’s one more catch: It is difficult to discern which tasks AI will and won’t succeed at. Mollick elaborates:

“The problem is that the [jagged frontier] is invisible, so some tasks that might logically seem to be the same distance away from the center, and therefore equally difficult — say, writing a sonnet and an exactly 50 word poem — are actually on different sides […]. Similarly, some unexpected tasks (like idea generation) are easy for AIs while other tasks that seem to be easy for machines to do (like basic math) are challenges.”

Further research suggests that while AI improves performance, it can also negatively impact employee job satisfaction, commitment, and sense of responsibility.

This is why the Harvard team refers to this technological frontier as “jagged.” Far from dependable, the capabilities of current AIs not only oscillate from task to task, but can also wildly shift the professional and personal incentives for human workers too.

People really can go on autopilot when using AI, falling asleep at the wheel and failing to notice AI mistakes.

Ethan Mollick

The challenge of AI integration

So while people may worry that AI is a job killer, it may in fact tend towards the opposite. These systems lack the ability to perform many of the tasks your average person does well. Instead, their niche will be churning through certain tasks quickly, saving workers time, effort, and resources for other tasks.

Even Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, noted: “The current systems are actually not very good at doing whole jobs.” He added AI will likely make workers “dramatically more efficient” rather than replace them.

The immediate danger, then, is business leaders who don’t properly assess the capabilities of generative AI systems and the challenges of integrating them into their operations. If they don’t properly map this “jagged technological frontier,” they risk losing the very people they need to make these systems productive and innovative.

Business leaders may let their people go, erroneously believing they can replace them with AI as a cost-cutting measure. Or workers may leave to seek jobs where they feel valued and can have a greater impact.

This is exactly where leaders of the entertainment industry appear to have stumbled. At the Milken Institute Global Conference, just days before the strike began, entertainment executives claimed it was inevitable that the industry would turn to AI. Producer Todd Leiberman said these systems would be writing scripts within a year. Rob Wade, CEO of Fox Entertainment, agreed but added that there would be a need for human “co-pilots.”

But as the Harvard study and other research suggest, Lieberman and Wade may have it exactly backwards. To remain competitive, businesses must keep people in the pilot seat and empower them to use AI as a co-pilot.

Keep humans in the driving seat

To do that, business leaders will need to listen to worker feedback regarding how to integrate AI into operations. They’ll also need to establish AI as a tool for innovation and efficiency — not as a taskmaster that strips people of responsibility, impact, and meaningful work. Finally, they must clearly communicate the value of human ingenuity and uniqueness.

“A radical redesign of corporate processes could spark all sorts of new value creation. If many companies do this, then as a society we’ll generate enough new jobs to escape the short-term displacement trap,” Behnam Tabrizi, a professor at Stanford University’s Department of Management Science and Engineering (and Big Think contributor), and Babak Pahlavan, founder of NinjaTech AI, write for the Harvard Business Review.

These appear to be the costly lessons the entertainment industry learned at the end of a months-long strike. As part of the deal, studios now agree to meet with the Writers Guild to discuss plans for AI use. They also can’t use AI to write or rewrite materials in ways that undermine a writer’s credit. And while writers have the option to use AI during their creative process, they can’t be required to do so.

It will take time to determine if the deal represents the blueprint for a redesign across the entire entertainment industry. For all other business leaders, now is the time to start mapping out their respective frontiers.