Beyond Spinoza’s “conatus”: How to disrupt workplace inertia and thrive

- Conatus is the deep, primal need we all have to survive. It’s about preserving our existence by any means.

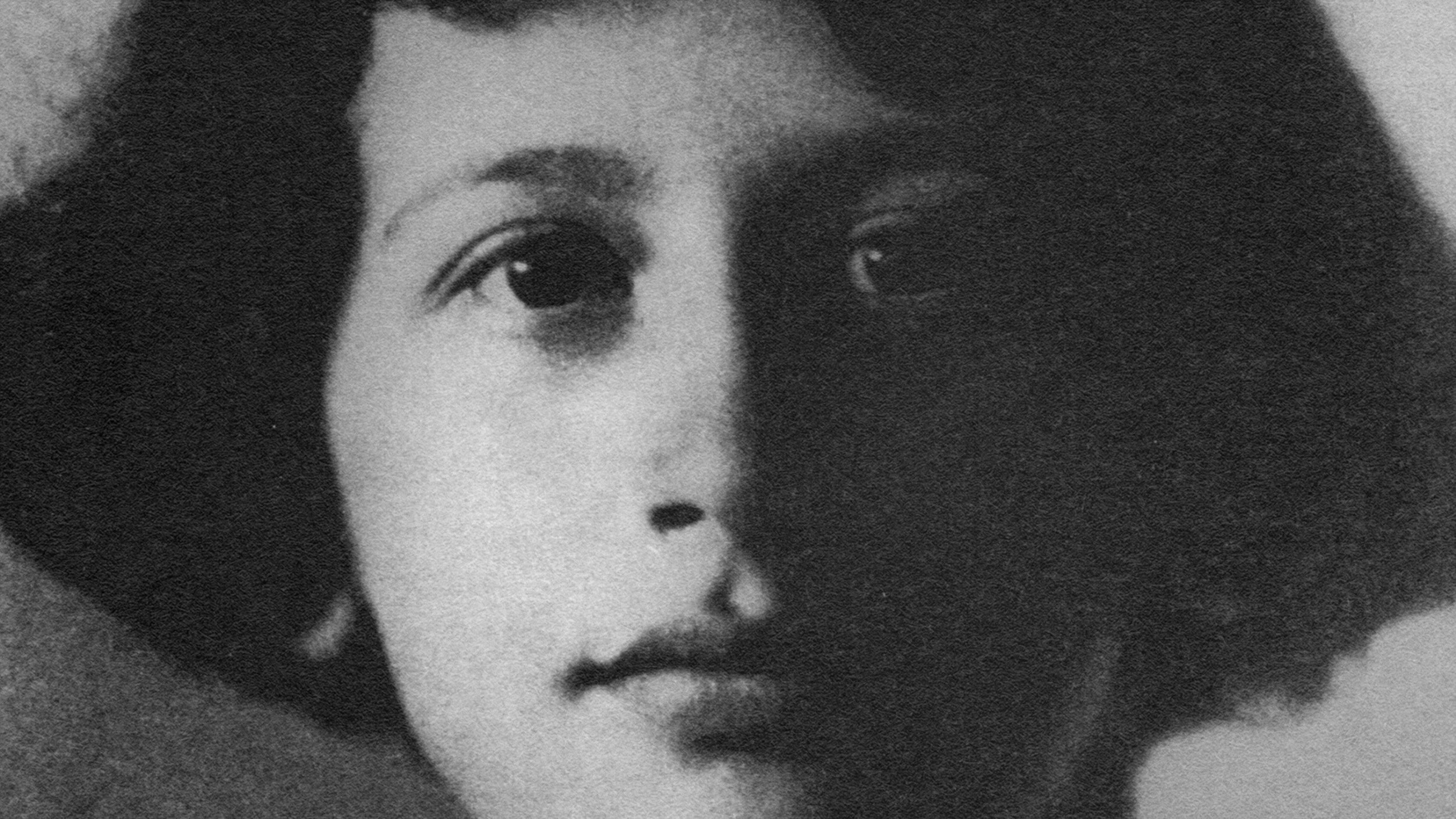

- As Hannah Arendt knew, surviving is not enough if we are to thrive. This is never more true than at work.

- Here, we offer three ways to keep conatus at bay.

In 1954, the zoologist Heini Hediger introduced us to the idea of “critical distance.” All living animals have a “critical distance.” This is how close a threat has to be before an animal will fight back. When faced with danger, most animals revert to “fight or flight.” And, for most species, their “I’m outta here” radius is far wider than their “Right, let’s have at it” one. Which makes sense. Running away will almost always mean you live for another day with all of your limbs.

The critical distance point, though, is when an animal will lash out. It’s the moment when, no matter how obviously they’re going to be obliterated, an animal will charge, snap, thrash, and claw its way to the grave. That near-universal will to life was what Baruch Spinoza called “conatus.”

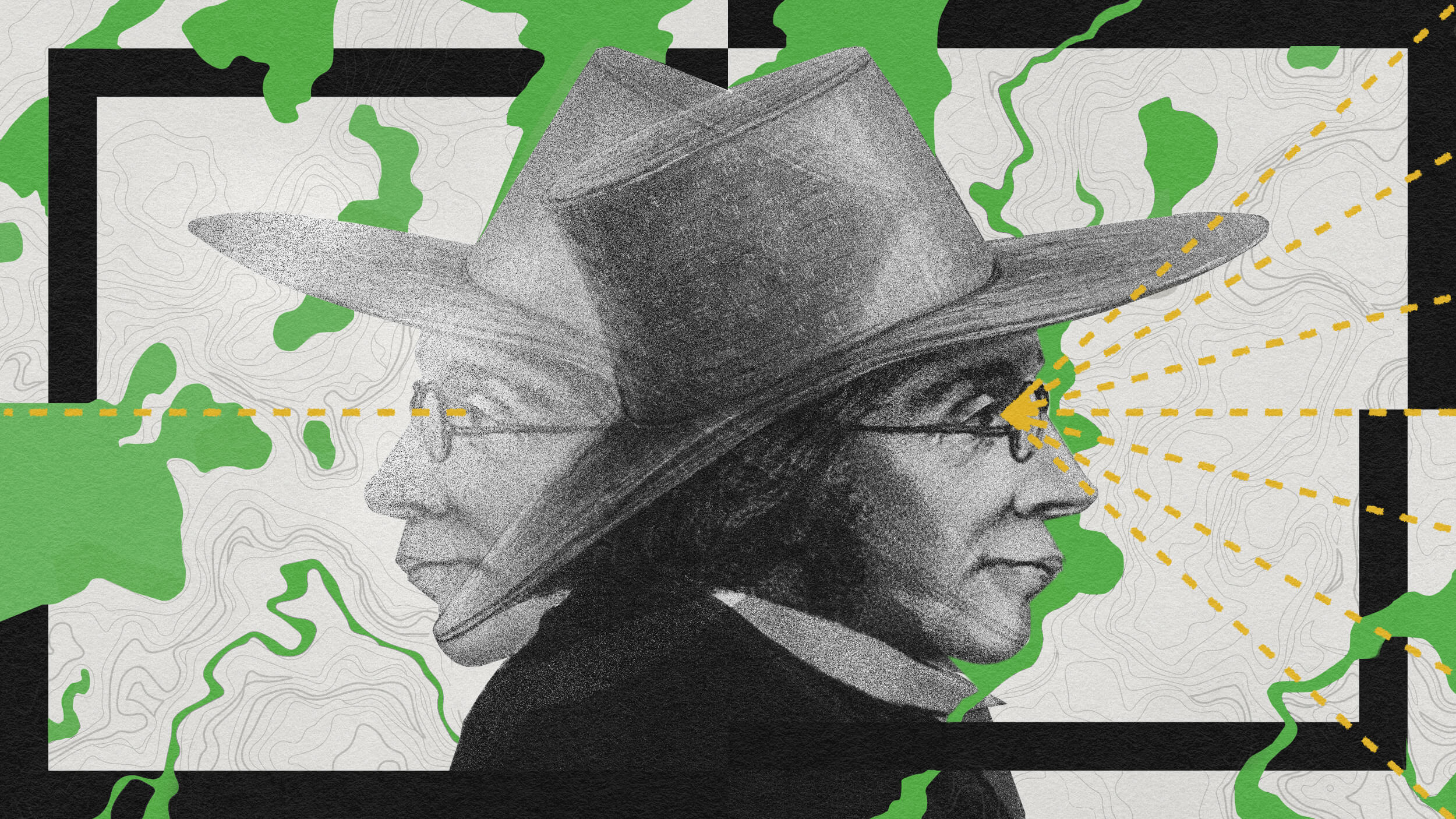

Conatus is what drives our critical distance. It is the essence of living. It’s how “each thing, as far as it can, by its own power, strives to persevere in its own being.” When we strip away the airs of modernity to look at the human condition most bare, what you see is an animal, desperate to carry on. In the 19th Century, Friedrich Nietzsche gave us his idea of the “will to power,” which he believed was our natural propensity to dominate and assert ourselves. But, two centuries before that, here we have Spinoza giving us a much more basic point: before we do anything, we simply carry on. Before the will to power is the will to preserve.

The problem, though, is that simple preservation is not enough — it’s not enough to survive; we need to thrive. Waking up every day, unchanged and unstimulated, is a recipe for misery. It’s the very definition of stagnation. As we shall see, it’s a siren’s call for both individuals and companies. It’s a call we need to ignore.

Asserting yourself on the world

When Spinoza talked of conatus, he did so with lashings of religion. Spinoza believed that we each possess a kind of soul, which he thought to be an element of the godhead. (Spinoza was accused of atheism, but it’s more accurate to call his position pantheistic.). Conatus, then, is the divine indestructible within us, willing itself to be alive. The spirit cannot be destroyed, so our basic, tugging need to continue is the voice of God asserting itself in the transiency of the world. It’s immortality staring down at mortality.

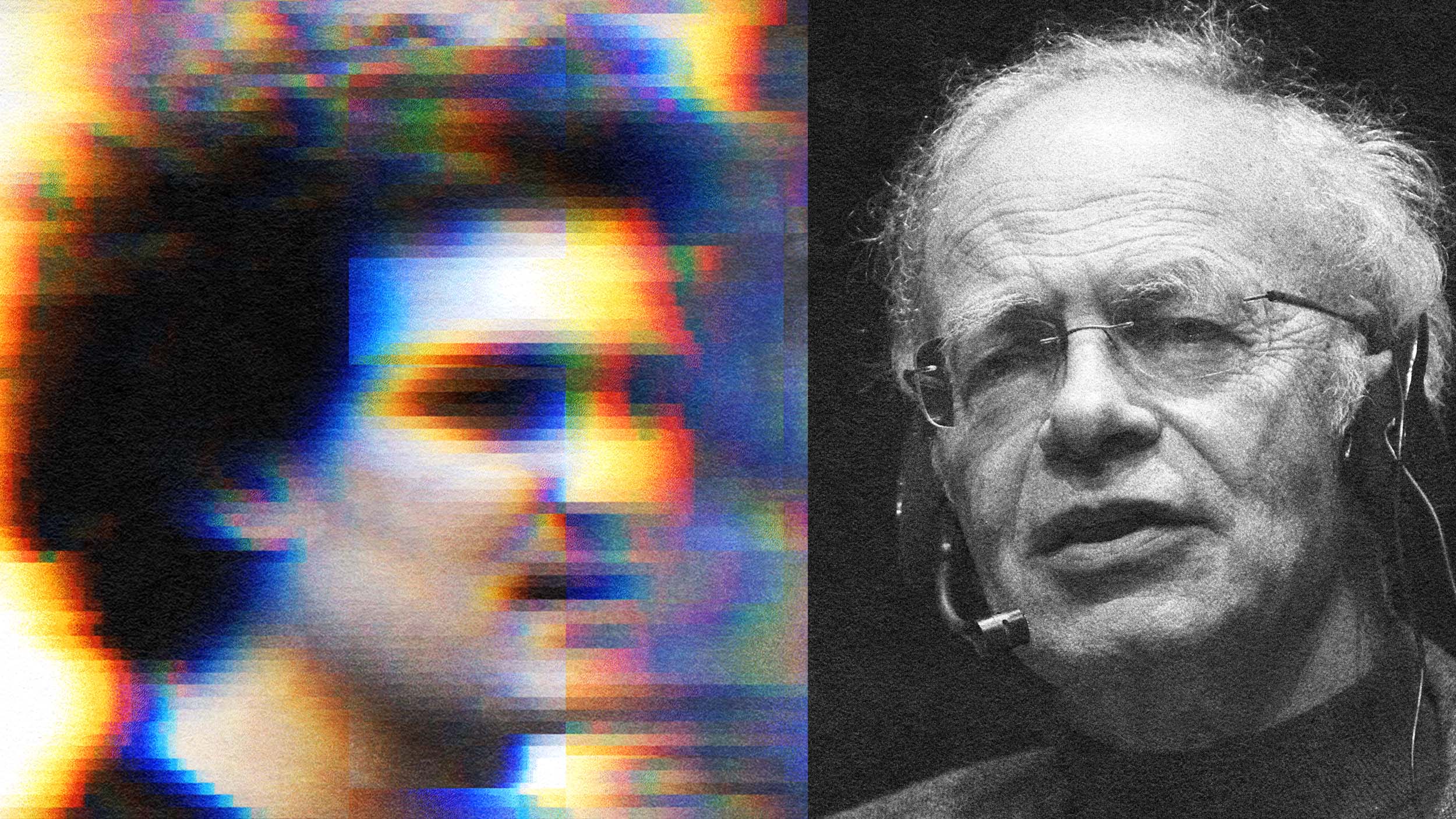

Today, some people might prefer to talk of evolutionary wiring. We are biologically primed to live and carry on — first to reproduce, and then, second, to secure the longevity of our offspring. Once that job is done, we might as well die. But this view of life — as one of coasting along until our biological purpose is complete — is hardly a recipe for happiness. A human being is not some moss clinging to some tree. We are a shouting, running, laughing, crying, fighting, restless species. As the phenomenologist Edmund Husserl knew, our attention is always directed outward. We always have one eye on the future. We move forward.

A life that stews for too long in listless, sustaining conatus will become unhappy. The philosopher Hannah Arendt called this “labor.” It’s when you spend your entire life simply returning to the start. You devote all your energy to staying still — a treadmill existence. The point of life, though, is to go somewhere.

How to conquer workplace inertia

How can we make sure that we do not languish in conatus at work? How can we avoid the trappings of Arendt’s “labor”? Here are some things to look out for and ways to help:

Set challenging goals. It’s hardly a state secret that you can, in many jobs, coast. You can turn up, do only as much as your contract stipulates, and clock out at the factory whistle. Which is fine. For a lot of people, that’s all they want to do. But for anyone to turn a job into a vocation and turn conatus into impetus, employees need to set regular goals that stretch and challenge them. According to a 2021 study, those who engage actively in the goal-setting stage are more likely to act on it. If you invest the time in planning your professional development, you’re more likely to enact it. So, the next time you get your annual self-assessment form, give a little bit of yourself to the task. It’ll add a bit of verve to your year.

Create a feedback loop. So, you’ve put in the hours and you’ve actively engaged in your goal-setting. It’s going well, but when a few days become a few weeks, that self-assessment form starts to seem like ancient history. It’s filed away in your bottom drawer and saved in that folder you never reopen, ever. Goals are pointless if you don’t keep coming back to them. And so, you need to be disciplined enough to reappraise them now and then. For the vast majority of people, this is hard, so it helps to have a manager who employs “continuous feedback.” This is not a euphemism for “Big Brother is watching you,” but it’s a way for managers to keep goals in sight. On Big Think+, we have an interview with Josh Bersin, Principal at Bersin by Deloitte, on how to do this well. Don’t be Big Brother; be a good manager.

Work with good friends. The hirsute ancient Greek polymath, Aristotle, once divided friends into three types: those of utility (who served a purpose), those of pleasure (who were good for a laugh), and good friends (who support you and wish you well). Work is, for a lot of people, made up of the first. You work with colleagues, not friends. Your “friendship” will last only as long as the utility of the relationship lasts. But Aristotle’s point was that friends of utility will not let a person thrive. They make the job easier, yes, and make the company more efficient, but you won’t grow if you only have colleagues. According to various studies, having friends at work — good friends — makes you happier, more effective, and keeps conatus at bay.