Why Van Gogh Is Ready for His Close Up

“All right, Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up,” says washed-up silent film star Norma Desmond in the final scene of Billy Wilder’s unforgettable 1950 film Sunset Boulevard. Gloria Swanson caps off her Oscar-nominated performance as Norma by walking into the camera’s lens and revealing in that final close up the full extent of her sick and tortured mind. In Van Gogh: Up Close, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through May 6, 2012, Vincent Van Gogh seems finally ready for his close up, too, but with an opposite effect. The mad, sad, and dangerous to know Vincent seen through the telephoto lens of legend gives way here to a clear-eyed view of an intensely focused artist who, despite personal difficulties, achieved greatness in art and communed intimately with nature in a way not only artistically revolutionary, but also therapeutic for himself and others. “All right, art loving public,” Van Gogh: Up Close shouts, “I’m ready for my close-up.”

We all love the cosmic Vincent of Starry Night, perhaps even while imagining Don McLeanwarbling in the background. Generations have also embraced the frail Vincent who was too good, too pure, too visionary, too everything for this world. Both extremes—the triumphantly universal and the tragically tiny—lose sight of the man himself: a working artist who interacted with other artists of the time, voraciously read the ideas of the best writers in three different languages, and painted not to let his inner demons play but, rather, to hold them at bay. We’ve had so many “Vincents” over the years since Irving Stone’s Lust for Life gave the young, manly Kirk Douglas something to sink his acting chops into in the film of the same name. The virtual slideshow of Van Gogh personae flits by so quickly as to become one big blur. Van Gogh: Up Close slows the spinning kaleidoscope down and zooms in on the artist by showing how he himself zoomed in on nature ultimately to find himself.

Five years in the making, Van Gogh: Up Close first sprang from the mind of internationally renowned Van Gogh scholar Cornelia Homburg. Homburg noticed a pattern of close-ups, or sections of minutely observed natural details, in many of Van Gogh’s paintings dating from the last 4 years of his life. “What could look at first glance simply like a formal matter of constructing a composition, upon further examination turns out to be a more significant concept with broader implications,” Homburg writes in the catalog to the show. Dating new approaches to content and composition to Van Gogh’s stay in Paris from 1886 to 1888, Homburg sees him “pursu[ing] them with tenacity and increasing virtuosity until the end of his career in 1890.” She concludes with the belief that “[b]efore the 1890s, no other Western artist had pushed the boundaries of close-up views of nature as far as Van Gogh.” Working with the estimate that approximately one quarter of all Van Goghs post 1887 feature some kind of close-up, the curators scoured the globe for the best examples to prove their thesis—and succeed beyond even their wildest hopes.

For everyone who sees the title of the show and thinks that the last thing the world needs is another Van Gogh show, Van Gogh: Up Close quickly disabuses you of that idea with a refreshing selection of gems from museums around the world, including a half dozen from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. A still life with the innocently conventional title of Grapes, Lemons, Pears and Apples explodes from within as visual shock waves scatter the “still” fruit across the canvas. In TheLarge Plane Trees, a series of truncated tree trunks dominate the scene with twisting abandon. As PMA curators Joseph Rishel and Jennifer Thompson note in the audio tour, the title figures in Sheaves of Wheat seem to dance across a bucolic ballroom rather than stand motionless. In the enigmatic Undergrowth with Two Figures, Van Gogh entraps a man and woman in a prison of regularly spaced trees in a spooky, pseudo-Symbolist scene that could easily be signed “Munch” in the corner. The sheer diversity and productivity of such a condensed period will stun you. “With things from nature you’re the only one there who thinks,” Paul Gauguin told his former housemate in 1890. Van Gogh: Up Close shows you Vincent thinking and re-thinking existing genres and making them uniquely his own, primarily by looking closer than anyone ever had previously.

In contrast to the lone genius myth, this exhibition situates Van Gogh firmly in the context he lived and worked in. Jennifer Thompson examines in her catalog essay the influence of Van Gogh’s exposure and interaction with both the Impressionists and the Post-Impressionists. Thompson sees Van Gogh’s “abundant use and adaptation of the close-up devices employed by [others as a way to] increasingly distanc[e] himself from avant-garde artists in Paris.” Joseph Rishel continues the focus on Van Gogh’s alien (and alienating) nature by emphasizing his Dutchness rather than his Frenchness by placing Van Gogh’s close-ups beside similar zooms by Rembrandt, van Ruisdael, and others. Ulrich Pohlmann even takes on the challenge of reconciling Van Gogh’s close-ups with the landscape photography of the time, admitting that it’s all hypotheticals and parallels until conclusive proof is found, but drawing fascinating zeitgeist-ish conclusions nonetheless.

Perhaps the key link between Van Gogh and the world illustrated by these close-ups is Van Gogh’s use of nature as a means of salvation. When overexcited or troubled, Vincent felt “obliged to go and gaze at a blade of grass, a pine-tree branch, an ear of wheat, to calm myself.” His singular focus on those details finds expression in these painted close-ups. National Gallery of Canada curator Anabelle Kienle cites a variety of sources, including Van Gogh’s Calvinist upbringing, his love of Japanese prints and their depiction of nature in art, and his reading of authors such as Thomas Carlyle. I’d like to add Walt Whitman to that list, especially when you start talking about blades (i.e., leaves) of grass.

Van Gogh praised Whitman in a letter to his sister Wil in 1888, saying that his poems “make you smile at first, they’re so candid, and then they make you think, for the same reason.” Looking at the way Van Gogh’s close-ups explode into meaning from tiny detail, I couldn’t help but think of the same explosiveness of the signature moment of Leaves of Grass:

A child said, What is the grass? fetching it to me with full hands;

How could I answer the child?. . . .I do not know what it is any more than he.

I guess it must be the flag of my disposition, out of hopeful green stuff woven.

Or I guess it is the handkerchief of the Lord,

A scented gift and remembrancer designedly dropped,

Bearing the owner’s name someway in the corners, that we may see and remark, and say Whose?

Richard Shiff in his (dense but rewarding) catalog essay examines this tension between abstraction (layering meaning onto a blade of grass) and distraction (losing sight of the grass) in Van Gogh’s close-ups. Both Van Gogh and Whitman preserve the physical while seeing the spiritual in the tiny details of nature. Both artists see the “handkerchief of the Lord” in those small things and pick it up as a token left behind for a true lover and believer.

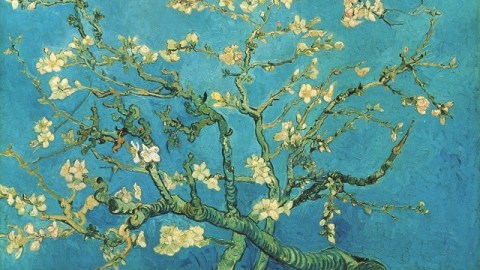

The show ends with a note of joy and triumph in Van Gogh’s Almond Blossom (detail shown above), a near-miraculous loan from the Van Gogh Museum. Van Gogh painted this close up of blossom-covered boughs set against a clear-blue sky as a gift for his newborn nephew and namesake, a living, loving tribute by his brother Theo. The family kept the painting over the mantle for years as a reminder of the great artist in their family tree. It’s a great painting and a great story of love and happiness that doesn’t fit with the standard story of the mad, suicidal genius. Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith’s recent scholarly but depressing biography Van Gogh: The Life (which I reviewed here) controversially argues that Van Gogh died in an accident rather than by his own hand. After seeing Van Gogh: Up Close, that theory doesn’t seem so controversial. Van Gogh had a lot to live for—from friends and family down to the grass beneath his feet. After over a century of distorted portraits, Van Gogh: Up Close brings us the real Vincent—troubled, yes, but a thinking, feeling, and loving person after all.

[Image:Almond Blossom (detail), 1890. Vincent Willem van Gogh, Dutch, 1853-1890. Oil on canvas, 28 15/16 x 36 1/4 inches (73.5 x 92 cm). Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.]

[Many thanks to the Philadelphia Museum of Art for the image above from, a review copy of the catalog to, an invitation to the press preview for, and other press materials related to Van Gogh: Up Close, which runs at the museum through May 6, 2012.]