Why the Newtown Shooting Made Me Think of This Painting

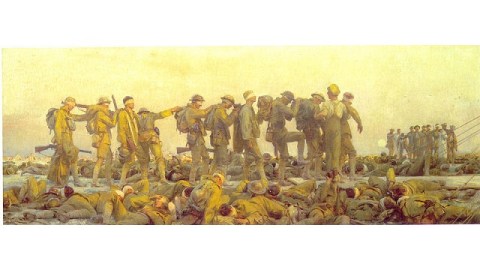

Like most Americans, upon hearing of the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, last week, my first reaction was disbelief. How could this happen? Why did this happen? How and why did this happen yet again? Like President Obama, I reacted as a parent as my thoughts raced to the possibility of my own children caught in such an attack. As I slowly digested the news (and as the news itself clarified earlier errors in reports), I kept coming back in my mind to Shannon Hicks’ photograph of Connecticut State Police leading children away from the scene as the children kept their eyes tightly closed and clung to one another in a long human chain. Then my mind linked that image to a painting that has long stuck in my mind—John Singer Sargent’s Gassed (shown above, from 1918-1919), his depiction of World War I soldiers blinded by mustard gas being led in procession to medical care. There are so many things to say about this incident, but these two images put together, at least for me, cut to the heart of what meaning we can draw from it.

By the time that Hicks took that photograph of the children fleeing the school, Adam Lanza had already taken his own life and that of 7 adults (including his mother) and 20 children using a Bushmaster XM-15 rifle and other weapons. Principal Dawn Hochsprung, school psychologist Mary Sherlach, and teachers Victoria Soto, Anne Marie Murphy, Rachel D’Avino, and Lauren Rousseau all died trying to protect their students. One six-year-old student survived the massacre of her classmates by playing dead until Lanza left the room. Covered in blood, she told her mother, “Mommy, I’m OK, but all my friends are dead.” Teachers and other adults begged the children to keep their eyes closed to avoid witnessing the horrific scene that one little girl could not avoid.

When the British Ministry of Information commissioned Sargent to paint a scene for public consumption from the Great War, they probably didn’t guess that Sargent would exercise the artistic license they gave him to depict a string of soldiers blinded by chemical weapons (and blindfolded with bandages) being led to medical assistance by orderlies. Sargent personally witnessed that scene along the Western Front and immediately grasped upon it as a metaphor for the maelstrom of emotions and beliefs surrounding the war, which was then grinding towards its end on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918.

For Sargent, the soldiers’ blindness must have embodied the many forms of blindness surrounding the war: the blindness of nationalism, the blindness of a generation acting as an accomplice to its own destruction, and, perhaps worst of all, the blindness of strategists employing 19th century “once more into the breach” tactics against the mercilessness of 20th century mass murder technology. And, yet, the blinded men stand full size in the immense painting and assemble as an ancient frieze formation with all the dignity of the classical ideal. Without blaming the victims, Sargent finds a way to speak about the loss of vision on every level.

Similarly, Hicks photo encapsulates all the forms of blindness involved in the tragedy: the momentary blindness enforced on the children in a society that inflicts violence on them daily through everything from entertainment to infotainment, the blindness of a political system paralyzed by special interests to the staggering statistics of gun-related deaths in America versus other industrialized countries, and the blindness of those so paranoid of the government, minorities, and whatever else that they fear that only an arsenal can assuage their anxiety. But whereas Sargent’s soldiers gain dignity from their pose, Hicks’ children only seem more vulnerable with their eyes closed.

Navigating the sea of commentary over the last week, I found The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik’s voice to be the most compelling and honest. In his essay, Gopnik decried “the child-killing lobby—sorry, the gun lobby.” Cutting to the heart of the matter, Gopnik screams, “In America alone, gun massacres, most often of children, happen with hideous regularity, and they happen with hideous regularity because guns are hideously and regularly available.” For him, “[t]he people who fight and lobby and legislate to make guns regularly available are complicit in the murder of those children” because “[t]hey have made a clear moral choice: that the comfort and emotional reassurance they take from the possession of guns, placed in the balance even against the routine murder of innocent children, is of supreme value.” With supreme acidity, Gopnik “congratulates” those he sees complicit in this tragedy and all the others “on living in the child-gun-massacre capital of the known universe.”

Perhaps Sargent’s war painting flashed into my mind because America today feels like a war zone with the increasing level of gun violence. The shooting at Newtown shocks us because of the numbers involved and the ages of those killed. But children die by gunfire here every day with a numbing regularity. To me, the answer is simple: less access to weapons designed solely to kill people and more access to mental health care for those who could possibly use those weapons to kill people. On the morning of the shooting, I was at my first grade son’s school for a holiday sing-a-long gathering celebrating children, family, and community. Coming home and hearing the news, those things we celebrated took on even greater importance. No matter how we think about what happened, the important thing is that we think about it and see the issue clearly with eyes wide open.

[Image:John Singer Sargent. Gassed, 1918-1919. Image source here.]