Who Killed the LA MoCA?

If “LA MoCA” sounds to you like something you’d order from Starbucks, then you probably don’t know anything about the recent kerfuffle surrounding what is being called the murder of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art. Like any great murder mystery, this one features plenty of high-profile suspects—some physically present, others purely metaphorically. The fact remains that the MoCA’s severely, if not fatally, wounded by the forced resignations of curators, subsequent resignations of artists on the board of trustees, bad reviews of questionably designed exhibitions, and the highly questionable conflicts of interest surrounding former (and possibly present by proxy) art dealer turned MoCA director Jeffrey Deitch. As sad as the current state of what was once known as “the artists’ museum” is, the real mourning is over whether this is just the first fatality in what might become a cultural serial murder.

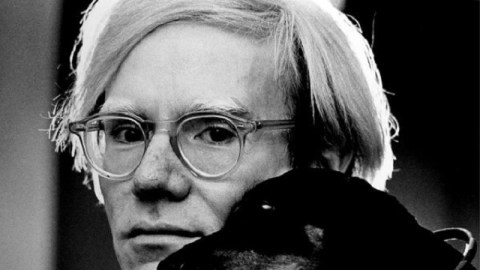

So, who are the suspects? Suspect number 1 kills from beyond the grave—Andy Warhol (shown above, in a sinister Dr. Evil mood). According to Los Angeles Times art critic Christopher Knight, Warhol’s “ghost… hovers in the background — and sometimes steps into the foreground — of almost every exhibition conceived by Deitch in the last 18 months.” Knight, a prominent national art critic as well as the hometown voice of the visual arts in Los Angeles, calls the last year and a half of MoCA exhibits “as boring as having the same Campbell’s soup every day for lunch,” a jibe at Warhol’s explanation for his fascination with painting the Campbell’s Soup Can series. Knight goes on to connect the dots between each of these exhibitions and Warhol, often in a strained way that is as informative and enlightening as connecting them to Kevin Bacon. As an intellectual exercise, I was able to do the same thing with my local museum—the Philadelphia Museum of Art—and Cezanne, with a lot less strain. Some artists are just that central to the narrative of art history, as Knight would agree in the case of Warhol, but he thinks the MoCA’s taken it too far. “The dull monotony, though, explains much of the dissatisfaction with the program,” Knight concludes. “Its narrow focus is repetitious and terribly dated. Nostalgic Warholism isn’t all there is in art today.” Warhol is at least an accomplice, if not the one who pulled the trigger.

Jed Perl of The New Republic offers a more interesting metaphorical murderer—Robert Rauschenberg! Although dead since 2008, Rauschenberg’s spirit, or at least his goal, “to work in the gap between art and life” is the “Pandora’s Box” opened by the MoCA. Perl sees Rauschenberg’s position as a “compromise position” that museum people should have avoided. “The museum has not been redefined so much as it has been disassembled,” Perl rails, “its coherence shattered as curators, administrators, and trustees grapple with the insoluble problem of operating in that nowhereland between art and life. Everything becomes the justification for everything else.” The tipping point for Perl and pretty much every other critic seems to be the upcoming MoCA exhibition titled Fire in the Disco, which plans to examine the cultural significance of the 1970s musical fad, which Deitch unfortunately likened to Cubism in terms of artistic impact. The MoCA melee sent Perl flashbacking to his post-press preview trauma over the 1998 Guggenheim exhibition called The Art of the Motorcycle. That exhibition “was not really about motorcycles,” Perl argues, but rather the idea that “all cultural institutions are pop culture institutions” and “preaching to the Wall Street types who were hankering for some cultural glamour, telling them it didn’t matter if they didn’t know or care what distinguished a Mondrian from a Kandinsky.” In Perl’s eyes, Deitch is just doing what all the contemporary art world is doing, just a little better and bigger. That the MoCA’s reeling is a sign for Perl that we may have finally reached some “moment of truth.” What hath Rauschenberg wrought?

The most obvious suspect is, of course, Deitch himself. Plenty of fingers are ready to point at him, as they have been since he accepted the position of director. Jason Edward Kaufman of ArtInfo calls Deitch the “merchant of bling,” more fixated on profit than probing the ins and outs of art history. “We are on a highway to the bottom in America, and in the art world Jeffrey Deitch is leading the charge,” Kaufman bombastically begins his piece. “When Deitch was installed the writing was on the wall,” Kaufman contends, knowing that the result would be “[t]he traditional audience would fade away, the youngsters would recognize MOCA’s pandering, and the institution would become an intellectually vacant party palace.” Kaufman calls for Deitch’s resignation, but it sounds like even he believes that irreparable damage has been done. When artists Catherine Opie, Barbara Kruger, Ed Ruscha, and John Baldessariquit the board of trustees, the MoCA, which had been founded in 1979 (yes, in the days of disco) by 150 artists looking for a new venue for contemporary art in Los Angeles, truly died.

If you ask me who killed the MoCA, I would hand you a mirror. What killed the MoCA is a mindset in America—a misguided mindset in which the skill set necessary for business success has become the template for success in every field. Just as some people want the president to be the “CEO in chief,” some saw an art dealer such as Deitch as the perfect candidate for museum director. Business leaders don’t create jobs, don’t legislate, don’t care about art history, and don’t care about educating the public—profit is the one and only goal. That single-mindedness works in our society as long as there are balancing forces that worry about everything else. Perhaps Perl is right and Deitch was just doing what he does best, but if we are to get the best of the spirit of Warhol and Rauschenberg as well as keep museums relevant and alive, then we must change our thinking before it’s too late.