What Makes Art Critics Change Their Minds?

Nothing hurts like a blown call. Baseball’s bittersweet beauty owes much to moments such as Umpire Jim Joyce’s missing a call to rob Detroit Tigers’ pitcher Armando Galarraga of a perfect game, that rarest of baseball feats, in 2010. In baseball, calls are irreversible. In the world of art criticism, however, a blown call can be reversed, sometimes years and years later. In the February 2013 issue of Art News, Ann Landi chronicles cases of art critics changing their minds. Split Decisions: When Critics Change Their Minds gently, but firmly pulls away the curtain of infallibility from the world of art critics, whether they like it or not. But more important than documenting these moments of minds changed is raising the question of what makes art critics change their minds.

Landi reaches back into the history of art criticism to take on the most influential (and most prickly) American critic of the 20th century, Clement Greenberg. “In the long and mostly unexamined history of critical flip-flopping,” Landi writes, “Clement Greenberg’s reversal on Monet may rank as one of the top ten of all time.” Greenberg called Monet’s late work “mere instances of his style but not works of art” in 1945, but in 1957, when Greenberg was in the midst of touting Jackson Pollock and the Abstract Expressionists, Monet suddenly, posthumously improved. “The righting of a wrong is involved here,” Greenberg backtracked, “though that wrong—which was a failure in appreciation—may have been inevitable and even necessary at a certain stage in the evolution of modern painting.” Don’t blame me, Greenberg pleads, blame the blindness of that “stage in the evolution of modern painting” I was writing in back in 1945. When Monet served his (and Pollock et al’s) purposes, Greenberg more than happily heaped on the praise for a “proto-AbEx.”

More recent examples from Landi’s article name two of the biggest art critic names in American journalism: The New Yorker’s Peter Schjeldahl and the Los Angeles Times’ Christopher Knight. Schjeldahl’s mea culpa involves Gustav Klimt’sPortrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I. Landi charges Schjeldahl with “not so much… a complete about-face on the glittering 1907 portrait” as with “downgrad[ing] it from a work of art that he’d called ‘transcendent in its cunning way’ six years earlier to a ‘largish, flattish bauble . . . classic less of its time than of ours, by sole dint of the money sunk in it.’” Perhaps blinded by Ronald Lauder’s $135 million purchase price in 2006, Schjeldahl gave qualified praise early on, but did that same price blind him in a different, perhaps hype-weary way to dismiss it later?

Whereas Schjeldahl flip-flopped on a canonical artist, Knight U-turned on a contemporary artist. In 1992, Knight wrote that sculptor/installation artist Nancy Rubins’ “mountainous pile of wrecked mobile homes and ruined water heaters startles with blunt force, but little resonance follows the initial, gee-whiz impact.” Then, just months later [n.b., edited from original post], Knight confessed he couldn’t not think of Rubins’ work: “A sculpture I can’t forget is one I criticized as unmemorable.” As Landi puts it, “The lesson from the earlier review ‘is fundamental,’ [Knight] wrote. ‘Art is experience, which needs to be trusted as it unfolds. The better part of criticism is in understanding that.’”

Knight’s confession should be printed as a disclaimer on all art criticism (including mine, of course). Knight writes about canonical and contemporary art, so he deserves understanding, especially when criticizing on the fly. Like poor Umpire Jim Joyce, Knight lives and dies call by call. What makes him a great umpire of art is this willingness to admit errors and to correct them, a luxury a baseball umpire doesn’t enjoy (for reasons I don’t understand and would happily argue over elsewhere). However, Knight’s correction comes a decade and a half later. How destructive to Rubins’ career was Knight’s review? She’s done well, so the effect, if any, was minimal. But how many careers were derailed by a bad review? Even worse, perhaps, and going by the old adage that there’s no such thing as bad publicity, how many careers never got going because an art critic didn’t find the artist interesting enough even for a bad review?

I like Knight’s characterization of art as an “experience, which needs to be trusted as it unfolds” and how “[t]he better part of criticism is in understanding that.” That understanding is the responsibility not only of the critic, but also of the critic’s reader. Don’t listen to me. Listen to your own mind, heart, and soul. The unfolding of art appreciation is a lifelong process. One of my darkest secrets as an English professor (my day job) is a lack of appreciation for the works of Jane Austen. Austen simply doesn’t speak to me, even though I know she should, but someday, in the great “unfolding” of my life, she might. In the art world, I once viewed Renoir as a second-rate Impressionist to Degas and Monet. Blame “Renoir overload” from the Barnes Foundation’s collection and/or my own immaturity, but further reading and some illuminating exhibits later, I can’t get enough Renoir now.

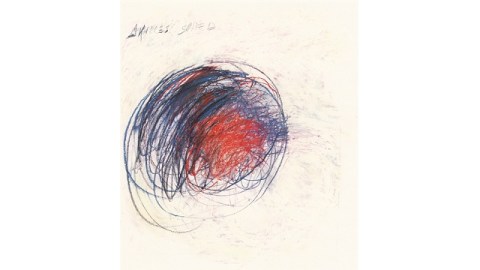

The great art enigma for me now is Cy Twombly. No matter how long I stand in the room at the Philadelphia Museum of Art containing his Fifty Days at Iliam, I still don’t get the fuss. Twombly’s Shield of Achilles (shown above), despite all the literary and classical overtones to tickle my English teacher fancy, still looks like one of my kids’ crayon scribbles. Yet, scholars and critics who’ve studied Twombly more extensively than I ever could, tell me there’s something of value there. So, in the name of intellectual honesty, personal improvement, and critical due process, I’ll keep trying to answer the question of why Cy. (The fact that Twombly’s father played major league baseball might help me stay in the game, too.) If I find religion with Twombly, is it possible that Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, my other two (perhaps better justified) “blind spots” will follow? The important point of all of this critical navel gazing is that no critic can pitch or call a perfect game, but the challenge is to know that fact and keep looking at and pitching ideas and images as you see them.

[Image:Cy Twombly. Fifty Days at Iliam. Shield of Achilles, 1978. Oil, oil crayon, and graphite on canvas.]