This Year’s Most Ironic Art Exhibit

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal”—truer (and more gender, class, and race specific) words were never written by a group of rich, white, male slave owners. The irony of each Independence Day often fades in the star-spangled spotlight of barbeques and fireworks. In the wake of the Supreme Court’s recent dismembering of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, however, that irony regained its biting edge. The confluence of the holiday and the court decision makes the timing of One Life: Martin Luther King Jr. at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, this year’s most ironic art exhibit. MLK spent his sole mortal life in the pursuit of equality everywhere in America, including at the polls, so honoring his life in images in the same town at the same time that the highest court dishonored his memory is too much irony to bear.

One Life marks the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom where MLK delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial not just to the attending crowd on August 28, 1963, but to posterity. A panoramic photograph from that landmark date in American history greets you as you enter the one-room exhibition, but the exhibit brings you the whole panorama of MLK’s life of service to his country. The images span the brief 13 years King spent in the public eye first as a civil rights advocate and later as a human rights advocate irrespective of race. From 1956, we see him both as a family man, with his wife and daughter, and as a man of action, riding the first integrated bus in Montgomery, Alabama, with Ralph Abernathy. Yousuf Karsh’s beautifully lit 1962 photographic portrait and Boris Chaliapin’s 1957 watercolor for a TIME Magazine cover each capture some of the aura of King’s charisma as he rose to national prominence. Just a year before his assassination, King appears in a Benedict J. Fernandezphotograph marching in New York City against the Vietnam War, the last crusade of his career (detailed beautifully in the PBS documentary Citizen King).

The intended highlight of the exhibition, of course, is the section on the 1963 March on Washington. Historical memory tends to leave off the “for Jobs and Freedom” section because of the power of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech’s call for racial equality someday, but that march was for jobs and freedom for all, as the official button from the march, showing white and black hands clasped in solidarity, reminds us. Bob Adelman’s photograph of MLK in mid oratory brings back some of the electricity of that day. Alas, the recent court decision short circuits the voltage of even that image.

For me, the new, ironic highlight of One Life is the photo of King locking arms with his fellow protestors as they cross Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, on the day known as “Bloody Sunday” for the violent response those nonviolent marchers received. That bloody day ignited a chain of events that led to the signing of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. A young John Lewis appears alongside MLK in that photo. Still bearing the scars from the fractured skull he sustained on “Bloody Sunday,” Representative Lewis called the court’s decision a “dagger” in the heart of civil rights, but he remains optimistic that congress will restore what the court has destroyed.

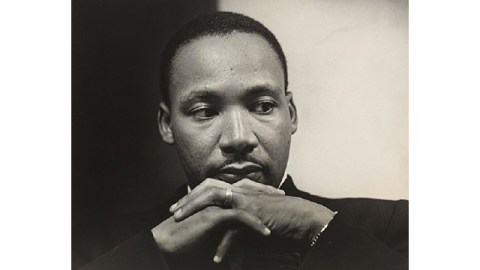

As Ann M. Shumard, curator of One Life: Martin Luther King Jr., explains in her “Curator’s Statement,” “it is important to remember King not merely as a dreamer but as a doer… Anyone can dream of a better and more just world. Martin Luther King Jr. dedicated his life to making that dream a reality.” It’s now up to a new generation to once more dedicate itself to making the dream of equality—the living out of the words of the Declaration of Independence—a reality. The online prologue to the exhibition quotes King’s words that “We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline… Again and again we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force.” When I try to imagine how King himself would have reacted to the court’s choice last week, I imagine him looking as pensive as in Jack Lewis Hiller’s 1960 photograph (shown above) of King after his release from Reidsville Penitentiary in Georgia, where a judge had sentenced him to four months’ hard labor in a notoriously violent state prison. An urgent phone call from Attorney General Robert Kennedy rescued King from almost certain death.

You can see King weighing his personal mortality in Hiller’s photograph versus the life of the cause itself. But even then King knew that “again and again we must rise” when those in power try to push the powerless down. The irony of One Life: Martin Luther King Jr. should remind us all that it takes more than one life, more than even one generation to win the battle for human rights, no matter how self-evident.

[Image: Jack Lewis Hiller. Martin Luther King Jr. shortly after his release from Reidsville Penitentiary, Georgia, 1960. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Gift of Jack Lewis Hiller. ©1960 Jack L. Hiller.]

[Many thanks to the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, for the image above and other press materials related to the exhibition, One Life: Martin Luther King Jr., which runs through June 1, 2014.]