The Old Ball Game… with Women?

To paraphrase Tennyson, in the spring, a young (or old) man’s fancy lightly turns to thoughts of baseball. It’s “love” in the original, or course. When I saw a notice for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s current exhibition “A Sport for Every Girl”: Women and Sports in the Collection of Jefferson R. Burdick, it felt like you could have both. Using trading cards from the late 19th and early 20th century, “A Sport for Every Girl” illustrates how women in sports were seen, or, more accurately, gawked upon, in those early days of American sports. It’s a fascinating glimpse backwards at what seem like grossly backwards times in terms of women’s rights and how sports in America reflected society itself.

Women played baseball throughout the early days of the sport in the 1800s. Women played on college teams played in the 1860s. Professional teams called “Bloomer Girls” (named for the trousers they wore instead of the full-length skirts worn in earlier eras) played from the 1890s into the 1930s. Anyone who’s seen A League of Their Own knows of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League that began when the men’s major league struggled to survive the manpower shortage during World War II. Unfortunately, as far as is known, none of the women depicted playing baseball in these cards really played baseball.

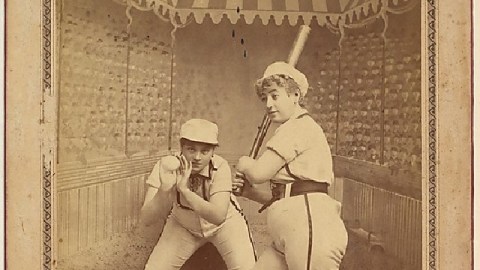

Little did I know growing up in the 1970s era of “big hair and plastic grass” that my Topps baseball cards with their inedible bubble gum descended from tobacco products. The earliest sports trading cards came bundled with cigarettes as a promotional item for adult men interested in sports. The proto-marketers at Allen & Ginter, one of the leading tobacco companies of the time, decided to mix in a little sex with their sports. Thus, the “girlie show” baseball cards featured in “A Sport for Every Girl” too often began as sexual sport for a male consumer. Fictional teams such as the “Black Stocking Nine” (shown above) and the “Polka Dot Nine” would be identified, respectively, by their dark stockings or by their polka-dotted neckwear they would hypothetically wear in their hypothetical games. In reality, the women would pose in baseball action positions in revealing (for the time) pants rather than full-length skirts. More than a hint of stocking would scandalize the general public, but for the almost exclusively male cigarette-buying public, these cards became the Maxim of their time, walking the edge of pornography but never crossing over.

You can see all the works in the exhibition online. It’s quite the education in gender politics and social sports history captured on cardboard. A series of “Gymnastic Exercises” features all the requisite gymnastic moves, but all performed in colorful, form-fitting outfits accentuating physical assets over agility. Old Judge and Dogs Head Cigarettes’s 1887 series titled “Occupations for Women” depicts women in ridiculous costumes “working” in then-considered equally ridiculous jobs as general, boat racer, body guard, and postman. The misogyny and condensation gets pretty thick in many of these images.

But not all of the images condescend completely to women. Some actually show women playing sports. Turkish Trophies Cigarettes featured Yachting Girl, Tennis Girl, and Basketball Girl in a 1913 card set. Golf Girl appears in Liggett & Myers Tobacco Company’s 1913-1914 campaign to promote Richmond Straight Cut Cigarettes. But just as you think women’s sports are being taken at all seriously, along come more 1880s cards featuring a chariot race and gladiators to set you straight that the sports are just an excuse for the stockings. The gladiators card actually visually quotes Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Pollice Verso, the 1872 painting that popularized the historically inaccurate “thumbs down” gesture, but the artistry ends there. However, at least for me, the way these cards act as visual artifacts is never ending.

Amidst all the misogyny and old school boys clubbery, one woman stands out as an authentic sportsperson regardless of gender—Annie Oakley. The famed female sharpshooter who starred in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show and who inspired the musical Annie Get Your Gun appears as the lone woman represented in the 1888 N28 Allen & Ginter card set displayed in the Met show. Miss Oakley’s card lists her as “Rifle Shooter” from the “World’s Champions” section of the Allen & Ginter series. The full sheet of champions featured gives a quick sign of the times as the sharpshooter appears alongside pugilists, oarsmen, and billiards players as well as baseball stars in those pre-NBA, pre-NFL, pre-NHL days. Oakley’s prowess with the gun proved “sexy” enough for sportsmen of the time to not have to mix in Danica Patrick-style cheesecake, too. How telling, however, is it that the one woman accepted into the male circle of champions was able to do so based on her skill with a deadly weapon rather than her skill at a less-deadly game?

In our post-Title IX country, it’s nice to think that we’ve achieved gender equality when it comes to sports, but there’s still a long way to go. “A Sport for Every Girl”: Women and Sports in the Collection of Jefferson R. Burdick, which runs through July 7, 2013, reminds us of just how far women in sports have come in a century and a half. And, yet, the Maxim feel of these exploitive photos still bothers me. Interestingly, Allen & Ginter was the first tobacco company to hire women, employing about 1,100 “girls” by 1886 to hand roll the cigarettes and, I presume, place cards such as these into the packages. Could some of those workers have been models, too? Even if they weren’t, one wonders what these women thought as they slid these images into the cigarette packs. If only baseball cards could talk.

[Image: “Black Stocking Nine,” from the advertising card series Cabinet Photos, Allen & Ginter (H807, Type 1), issued by Allen & Ginter (American, Richmond, Virginia), 1884-1885. Albumen print, cabinet card. Dimensions: Sheet: 6 1/2 x 4 3/16 in. (16.5 x 10.6 cm). The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick.]

[Many thanks to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for the image above and other press materials related to “A Sport for Every Girl”: Women and Sports in the Collection of Jefferson R. Burdick, which runs through July 7, 2013.]