The Bias Within The Bias

This article originally appeared in Scientific American Mind

Recall this pivotal scene from the 1997 movie, Men in Black. James Edwards (Will Smith, or Agent J) arrives at the headquarters of MiB – a secret agency that protects Earth from extraterrestrial threats – to compete with “the best of the best” for a position. Edwards, a confident and cocky NYPD officer, completes various tests including a simulation where he shoots an ostensibly innocent schoolgirl. When asked why, Edwards explains that compared to the freakish aliens, the girl posed the biggest threat. He passes the test: potentially dangerous aliens are always disguised as real humans. Agent K (Tommy Lee Jones) offers him a position at MiB and the remaining candidates’ memories are erased. They return to normal life without ever realizing that the aliens were a ruse – a device for Agent K to detect how sagacious the candidates really were.

This wily test of intelligence and mindfulness is defined by two characteristics. The first is that most people fail it; the second is a subtle trick intentionally implemented to catch careless thinking (the schoolgirl for example). Narratives in literature and film that incorporate this test go something like this: scores have tried and failed because they overlooked the trick – even though they confidently believed they did not – until one day a hero catches it and passes the test (Edwards). Game of Thrones readers may recall the moment Syrio became the first sword of Braavos. Unlike others before him, when the Sealord asked Syrio about an ordinary cat, Syrio answered truthfully instead of sucking up. (The ending of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade also comes to mind, but this does not fit the narrative for a critical reason. Those who failed did not live under the mistaken belief that they succeeded – they were beheaded.)

Here’s my worry. The same thing occurs when lay audiences read books about thinking errors. They understand the errors, but don’t notice the trick – that simply learning about them is not enough. Too often, readers finish popular books on decision making with the false conviction that they will decide better. They are the equivalent of Edwards’ competition – the so-called best of the best who miss the ruse.

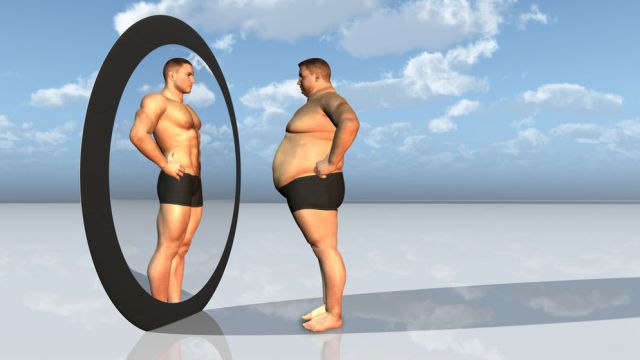

The overlooked reason is that there are two components to each bias. The first is the phenomenon itself. Confirmation bias, for example, is your tendency to seek out confirmation information while ignoring everything else. The second is the belief that everyone else is susceptible to thinking errors, but not you. This itself is a bias – bias blind spot – a “meta bias” inherent in all biases that blinds you from your errors.

Popular literature on judgment and decision-making does not emphasize the second component enough, potentially inhibiting readers from fully understanding the source of their irrationalities. Although we intuitively believe that we correct for biases after being exposed to them, it is impossible to truly accomplish this until we consider how the bias blind spot – the bias within the bias – distorts thinking. The ironic implication is that these books are perhaps part of the problem. The common sendoff, “now that you know about these biases, perhaps you’ll decide better,” instills a false confidence – it’s the trick we’re all failing to notice.

I first noticed this after learning about confirmation bias, overconfident bias and above-average-effects and concluding, dubiously, that I was a genius living in a world of idiots. Of course, the joke was on me, and it took many years to figure that out.

This effect appears all over the place when you stop to look around. Construction projects often finish late and over budget because planners, after researching previous late and over budget projects, confidently estimate that their undertaking will never suffer the same fate. Wars are the same. Iraq, some believed, would never turn out like Vietnam. Yet that attitude may have caused our prolonged stay. When we learn about thinking errors, we falsely conclude that they do not apply. That’s when we mess up.

The problem is rooted in introspection. Biases are largely unconscious, so when we reflect on thinking we inevitably miss the processes that give rise to our errors. Worse, because we’re self-affirming spin-doctors, when we introspect, we only identify reasons for our infallibility. In this light, we see why mere exposure to biases compounds the problem: they actually make us more confident about how we decide.

I admit that I’ve painted a rather pessimistic picture of human rationality. We are plagued by systematic biases, and reflecting on those biases only exacerbates the problem. Like knifing Hydra, every time we think about thinking errors we commit even more errors. It’s an epistemic Chinese finger trap. Is there any way out?

System 2 thinking – the ability to reflect and think deliberately – is capable of critical self-analysis. So I am ultimately optimistic about our Promethean gift. It’s impossible not to notice the power of reason, especially in the 21st century. It is one of our “better angels,” as Steven Pinker notes, and it has nudged us towards cooperation and the mutual benefits of pursuing self-interest and away from violence.

A note of caution, however. It’s crucial that we use our ability to reflect and think deliberately not to introspect, but to become more mindful. This is an important distinction. Introspection involves asking questions, yet we’ve seen that we’ll tend to answer those questions in a self-serving way. As Nietzsche hinted in Twilight of the Idols, “We want to have a reason for feeling as we do… it never suffices us simply to establish the mere fact that we feel as we do.”

Mindfulness, in contrast, involves observing without questioning. If the takeaway from research on cognitive biases is not simply that thinking errors exist but the belief that we are immune from them, then the virtue of mindfulness is pausing to observe this convoluted process in a non-evaluative way. We spend a lot of energy protecting our egos instead of considering our faults. Mindfulness may help reverse this.

Critically, this does not mean mindfulness is in the business of “correcting” or “eliminating” errors. That’s not the point. Rather, mindfulness means pausing to observe that thinking errors exist – recognizing the bias within the bias. The implication is we should read popular books on decision making not to bash rationality (that will backfire) but to simply reconsider it with an open mind. Instead of pulling harder to escape the finger trap, try relaxing. Maybe then you’ll notice the trick.

Image via CarolSpears