The Art of Keeping Our New Year’s Intentions

Having worked in fitness clubs for over a decade (and having worked out in them for two), I know this cycle well: the gym will be packed until mid-February. Attendance will die down until early May, when ‘beach season’ inspires people to hit the weights and mats. As summer properly kicks off, however, people spend more time outside, until realizing what has happened after Labor Day weekend. A small surge lasts through October, when holiday season makes it seem impossible to get to the gym…until New Year’s, when the cycle starts all over.

Celebrating the New Year is more ritual than holiday. A cultural and personal reset, this is the time when we all get to focus on what needs changing, habits we’d like to rid ourselves of, intentions set in motion. Yet intentions are only the first step: becoming a year-round gym rat (using the above example) requires discipline, focus, patience and, most of all, dedication.

Setting intentions is a powerful practice, though essentially useless without action. I’ve heard people express wanting to change without the willingness to put in the effort to make change happen. This form of ‘faith’ is like most others: it might make you feel better, but it’s meaningless without the discipline to make your goals happen.

And change often begins with our imagination—not the change that comes along with sudden tragedies, like the death of a loved one or a natural disaster, but the desire to incorporate better habits and ways of being into your life. The catalyst for such change is beautifully described by an ancient Vedic concept: maya.

Maya is often translated as ‘illusion.’ I’ve heard yoga teachers and Eastern-leaning philosophers say things like ‘All life is maya, an illusion.’ They then give a half-cracked smile and their followers nod in agreement, saying, ‘Wow, that’s so deep.’ Of course, that’s also meaningless, an odd rendering of a concept that has much more integrity than thinking reality is essentially not really reality—a mindset that allows you to not be disciplined, since it all ‘doesn’t matter.’

Professor of Religion William K Mahony translates maya as ‘creative force’ in his book, The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination. He writes,

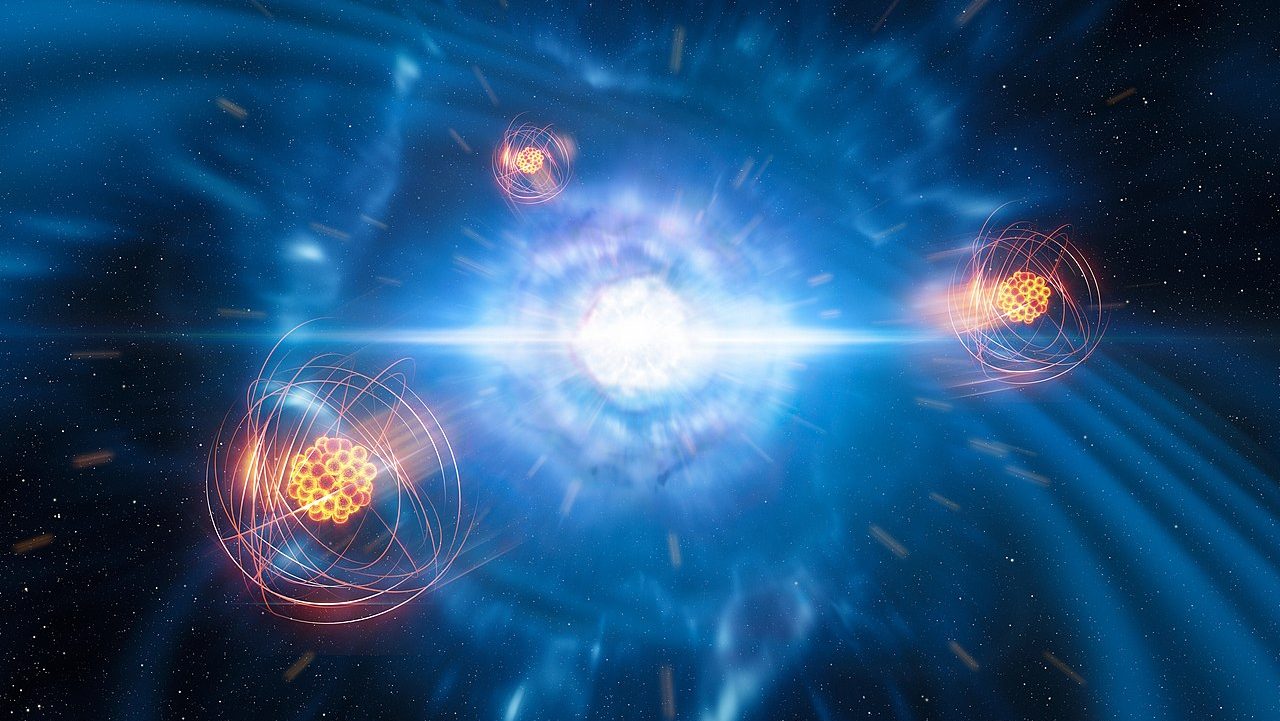

Early Vedic seers used this rich and important word to describe the marvelous and mysterious power by which the gods and goddesses were able through the power of the mind to create dimensional reality seemingly out of nothing.

Knowing now that the ‘gods and goddesses’ are a function of our brains trying to make sense of the ‘building’ of the universe, we can use Mahony’s insights (as he does later in this magnificent book) to use maya as an inspirational tool for building the world we want to create. His work is essentially a celebration of the imagination and the creative powers inherent in our brains.

Our minds create stories where none exist. This could prove to be one of the neural origins of religion: brain space once devoted to making patterns in nature for survival purposes are now utilized for spinning creation mythologies. The history of literature resides in the power of our imagination; indeed, this is a tool that should be developed, so long as we understand the at-times thin line between fiction and reality.

Everything we see is the result of maya: the computer or device you’re reading this one, the clothing on your body and the bed you’ll sleep in tonight were all envisioned before they were built. Maya is the force that provoked the reality of each.

In his book Phantoms in the Brain (the inspiration for one of the best TED talks ever), V.S. Ramachadran talks about the methods he used treating patients suffering from phantom limbs. Amputees sometimes experienced intense pain in limbs they had lost (even ones they never had, as in the case of one woman born without arms). For centuries this was written off as just being ‘in the mind,’ or the result of some desire to be ‘whole.’

Ramachadran saw beyond this unfortunate ideology, creating a mirror box: a cardboard box with a mirror in the middle. The patient sticks one arm in one side and his phantom in the other. By ‘seeing’ the phantom, his pain eventually yields. The doctor’s success rate has been startling. As a byproduct of this work, he also was a leading proponent of neuroplasticity, the fact that our brain has the ability to continually ‘change itself’ throughout life.

Interestingly, when patients tried to think about releasing pain in their phantom limb, nothing happened. It was only when actually using the mirror box that their brains were able to think that the limb had returned. They had to partake in the action, not merely the thought of the action.

As we enter this New Year, whatever intentions have been set will only be realized if we persist in the actions of change. Thinking about it or simply hoping it becomes what we want will remain phantoms in our minds, until next year we set a similar intention, and so on. Change occurs through action. The vision, maya, has to be there first, but from there, it’s up to us to follow through.

Image: docstockmedia/shutterstock.com