Study: Social Networks Spread Anger Much More Effectively Than They Spread Joy or Sadness

Maybe digital technology is a neutral medium, conveying all our thoughts and feelings equally well. Or maybe, as tech hype tells us, our apps and gadgets skew positive, liberating us to do good and be better. But this paper suggests otherwise. According to its analysis millions of posts on Weibo (China’s answer to Twitter), there is one emotion that spreads much more widely and quickly across the social network than any other. And that emotion is anger.

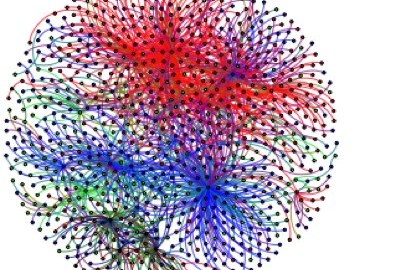

The authors—Rui Fan, Jichang Zhao, Yan Chen and Ke Xu of Beihang University—crunched through 70 million tweets posted on on Weibo in 2010, mapping both interactions among users and four key emotions they were expressing. (They began by using emoticons that expressed sadness, joy, disgust and anger, then used those to train a software agent to spot the characteristic language of each emotion in other, non-emoticonned tweets.) With this analytic framework, they had a way to characterize the emotions expressed in any given tweet and to map how that tweet was replied to and retweeted. They could then look for correlations between the mood of a tweet and the extent to which it was spread in the social network. That’s one of their figures above, illustrating this post: A network of Weibo tweeters, all of whom has at least 30 interactions with each other. Each point is a tweeter, each line is an interaction between tweeters, and the colors indicate the dominant sentiment that the tweeter put forth in the time sampled. Red is anger, green is joy, blue is sadness and black marks disgust.

These correlations, they write, “indicate that different sentiments have different correlations and anger has a surprisingly higher correlation than other emotions.” Contrary to their expectations, anger (and thus the news that triggers it) spreads wider than any other emotion. Even at three degrees of separation (a tweeter reacting to a tweeter reacting to a tweeter reacting to the original tweet) there was still a good chance that the latest tweet would be angry like the original. Joy spread less widely, and disgust almost not at all. Meanwhile, in a seeming illustration the Ella Wheeler Wilcox was right, sad sentiments appeared to have no influence whatsoever. Even people in immediate contact with the original tweet were apparently impervious to its mood. (When sad tweets do appear in clumps in their data, it is because sad news has hit everyone at the same time, the authors write. That’s different from a mood spreading from one tweeter to another.)

As many other studies have found, this one also determined that some people in the network had more contacts, and more frequent contacts, than average and were thus more influential. But here again, not all emotions were equal. The influentials were more effective at spreading anger and joy than they were at getting others to join them in disgust or sadness.

What gets people riled up? One spur comes from stories of government corruption and abuse of power—food contamination scandals and news that yet another group of people had been forced off their land for a development scheme were common triggers. The other was international incidents that offended Chinese national pride, like U.S. military exercises in the Yellow Sea or clashes with Japan over the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands.

“Our results,” write the researchers, “show that anger is more influential than other emotions like joy, which indicates that the angry tweets can spread quickly and broadly in the network.” Anger and the propagation of information are a dangerous combination. Last week, for instance, a video of Hindus getting attacked in Uttar Pradesh led to anti-Muslim riots that killed 44 people and displaced 42,000 more. The video turned out to be fake. Often people react by deploring the bad actions of strangers and wishing they would be more positive (“why don’t you report the good news?” is a question every journalist has heard a million times). But this research suggests we could use a better understanding of “emotional contagion” more than another “why can’t we all just get along” sermon.

Hat tip: Nicholas Christakis

Rui Fan, Jichang Zhao, Yan Chen, & Ke Xu (2013). Anger is More Influential Than Joy: Sentiment Correlation in Weibo arXiv: 1309.2402v1

Follow me on Twitter: @davidberreby