Searching for Shylock

Adapted From the Book: LIVING WITH SHAKESPEARE: Essays by Writers, Actors, and Directors.

The concept of Justice is an inherent sense that can be seen in any playground. Children spend as much time making up the rules for a game as they do playing the game, and are furious when the rules are broken. The American people are still suffering from the manipulation of the financial system by a bunch of crooks who not only got away with it, but are richer than ever. This is only the latest example of a justice system that is anything but blind; the public knows it, and in the 2011 touring production of the Theatre for a New Audience I strove with Shylock to embody their frustration.

The demand for Justice dominated my Shylock; I imagined myself as a Palestinian in an Israeli court, or a Chinese– Italian– Irish– Japanese– Black– Arab– Native American on trial. I wanted my audience to identify with Shylock in a deeply personal way, so much so that they would involuntarily nod and think, “Yes, I understand, I have been there.”

For me, the connection with his daughter was always the key to Shylock. Jessica runs off with her Christian suitor, Lorenzo, and takes with her all the money and jewels she can carry; her thefts include a turquoise ring which was given to Shylock by his late wife, Leah, when they were courting. His last connection with his great love Leah was important to him, of course, but the pain he goes through, the epiphany he experiences, is caused by his daughter’s disregard for the ring that she must have known was so dear to him. When Tubal tells him that a Genoan “showed me a ring that he had of your daughter for a monkey” (3.1.78), Shylock replies, “I would not have given it for a wilderness of monkeys” (3.1.80– 81). The great line leapt out at me the first time I read it, and I believe that this is the moment Shylock becomes another person, a lesser but very dangerous man. His greatness had been in his ability to rise above the crap that he had had to go through as a Jew each day, to remain aloof for the sake of his community, his daughter, and his faith; but the turn to actually consider claiming his pound of flesh— the mere thought of which is anathema, and which had perhaps initially been proposed as mere melodrama on his part— instantly damns him. Shylock, the smartest, most reverent person in the play, is completely aware of his damnation, as well as of the terrible violence it will bring to the Ghetto. Were he to carry out the penalty in his bond, there undoubtedly would be a pogrom and many would suffer, many would die. Yet he is unable to stop himself.

There is a distraction in the play when Shylock gets the news that Jessica has traded the ring away, which is this: How, amid all the stolen jewelry, when Tubal has simply called it “a ring,” can he know it is that particular turquoise ring? It’s an assumption that denigrates Shylock, and indicates a cynicism that is not characteristic of this superior man. In our modern production, the problem was solved with cell phones. We placed Tubal in Genoa, and had him send a photo of the ring to me; this provided me with the opportunity to be alone in my misery and to make that connection with the audience I so desperately wanted. There is only one moment in the play when Shakespeare gives Shylock a chance to address the house. In Act 1, Antonio comes on stage, and before Shylock speaks to him he says in an aside,

How like a fawning publican he looks!

I hate him for he is a Christian,

But more, for that in low simplicity

He lends out money gratis and brings down

The rate of usance here with us in Venice.

If I can catch him once upon the hip,

I will feed fat the ancient grudge I bear him.

He hates our sacred nation, and he rails—

Even there where merchants most do congregate—

On me, my bargains and my well- won thrift,

Which he calls interest. Cursèd be my tribe,

If I forgive him!

(1.3.28– 39)

That aside established a certain complicity, and I stretched it to the moment when Tubal texted the picture of the ring to me. Some actors do not like to engage the audience; I believe it is my long suit. After a shocked pause, I shared the picture of the ring with them, explaining, “It was my turquoise”— show

it, show it, look at it, pause, look at them— “I had it of Leah; I would not have given it for a wilderness of monkeys.” At this point I would be weeping, and then, clutching myself in pain, I would stumble toward a place to sit; once seated I began keening and dovening until Tubal got my attention once more on the cell phone. This description may sound ordered and cold, but in fact it affected me deeply each time. It was an extension of my explosive interpretation of the “Hath not a Jew eyes” speech, full of years of frustration and abuse culminating in the abduction, elopement, and betrayal of my daughter.

At this point Tubal says, “But Antonio is certainly undone,” to which Shylock answers, “Nay, that’s true, that’s very true” (3.1.82; 83). Those two lines should chill the audience as Shylock changes before their eyes; the expression “a weeping man is a dangerous man” becomes vividly clear. It is his pain that is his salvation, because no matter how far his vengeance carries him, if his anguish has been sincere the audience will continue to sympathize with him, up to the moment when he nearly kills Antonio. They may even wish I would go ahead and do it.

Antonio is one of the most difficult parts in the play, and ours, Tom Nelis, was stellar. I had never liked that character, never had any respect for him, until Tom said he had the impulse to do something when he was tied to the chair during the trial scene, right before Shylock is to cut out his pound of flesh. I told him not to tell me what it was, just to do it; he said it might be a good idea to let me know, but I insisted. That night while I was poised over him with murder in my eyes, he spat in my face. It was electrifying. And at that moment I suddenly had enormous respect for this Antonio, and he became deserving of my respect— my possible equal in the gentile world. I think it must be the first time in history that that has ever happened.

I had a connection with the role of Shylock that served me each time I did it. There’s no way to explain the phenomenon of an actor’s identifying with a character. This role is about much more than anti- Semitism— do we have to say that prejudice is everywhere? My objective was to make Shylock a human being, someone who continued to live long after the curtain went down. But that’s what I try to do with all my work. It’s what every artist tries to do, isn’t it? Create life.

* * *

Over the years I’ve become increasingly fascinated by the fact that the magical way in which figures such as Shylock come to life in theaters depends so strongly on elements as concrete as wood and plaster.

The Merchant of Venice has been dated to 1596– 1598; it would have opened at the Theatre in Shoreditch. The Theatre was torn down in 1598, and in 1599 its timbers were moved across the Thames to the south bank and repurposed to construct the Globe. The Merchant was a favorite play in the repertoire, and although there’s a gap in the Globe’s archives, there’s every reason to believe it was performed there too. These two three- story, open- air, polygonal amphitheaters with thrust stages welcomed different classes of people, from aristocrats to members of the bourgeoisie to those who paid a penny to stand in the round pit before the stage. There is also a record of The Merchant being performed twice at court for King James in the years 1604– 1605. With a ceiling, smaller dimensions, and an audience consisting of the king and his noblemen, the setting would have encouraged a very distinct performance. Before Shakespeare’s very eyes, The Merchant would have already been transforming itself in response to the forces of different theaters and different audiences.

A few years ago, I performed Shylock for the Royal Shakespeare Company’s “Complete Works.” The production opened in New York, and then went to the octagonal Swan Theatre in Stratford- upon- Avon. That is the greatest theater for Shakespeare I have ever performed on, and if you could interview the other actors in our show who played it they would tell you the same. The first time I stepped on that stage, I froze; not only at the history, but at the sudden confrontation with a stage unlike any I had ever played. The balconies are stacked one above the other, and you have to really take the audience members up there into consideration, because those in the back rows of the balconies are on high stools and must lean forward in order to see. It was one of the biggest jolts I ever had when I looked up and saw rows of people straining over the rails so as not to miss a thing. It’s only fair that you include them, that you take your time and really look, because you will see a bunch of people who are at this performance for one reason only: to see you do this play. And that lifted our performances beyond our expectations.

I had arrived a week before the company and had been working alone there with complete freedom of the stage all by myself. When the company got there, I watched their responses when they walked in and found that my first impression was not an illusion: they felt the same way. As good and as successful as our show had been in New York, it went to another level, truly, at the Swan. You may choose whatever descriptives you wish— “elevating,” “humbling,” “thrilling,” and so forth— they are not enough.

We also were suddenly burdened with the responsibility of proving our American worth in Shakespeare’s backyard. We needn’t have worried, however, for the audience stood and cheered on our opening night, and wouldn’t stop till we came out for a second company call. We sold out quickly and there was a queue at the cancellation window that went out the door to the street. It was the greatest affirmation not only of our work, but of the influence that a theater can exert.

That first tour of The Merchant visited only the two theaters, but the changes the setting made to the play were considerable, and it was then that I became keenly interested in this subtle, almost inarticulable, but very visceral relationship between a theater and a production. I had the chance to explore this relationship further with the Theatre for a New Audience when we took our performance of the play on a tour that comprised two coasts, four cities, eight weeks, and sixty- four performances.

The performances in this remarkable company have always been good, but the pressure of having to adjust to four very different theaters, after a cramped rehearsal space, refined us into a tough, tightly knit, self- assured Shakespearean troupe. We still feel we own this particular production of the play, and

I believe that reshaping our performances to fit each house had a great deal to do with this exhilarating feeling.

To begin with, a rehearsal space never relates to a theater apart from tape marks on the floor indicating the deck, entrances, steps, et cetera. None of this matters at first because at that point we are feeling each other out, testing rhythms and sounds, and learning how we fit together with this four hundred- year- old language. We were basically off book in a little over two weeks and anxious to get into the theater, because it’s always a surprise when you first walk out on stage after the security of a little room with your fellow actors as your only audience. Suddenly you’re facing a back wall that’s quite a bit further back than the five feet you’ve grown used to. The beautiful words you’ve shaped into meaningful expressions sound weak, tentative, and not at all like what you had in mind, simply because the chore now is to fill the house— to expand everything you’ve worked on to fill the needs of that particular space.

Our first theater, the Schimmel Center for the Arts at Pace University in New York City, is a 750- seat “letter box.” It’s very wide, for it was designed primarily as a lecture hall, with pullup desks on the seats. There is quite a gulf between the apron and the audience, and we had to overcome this separation while opening up from a 110- degree span to 180 degrees.

Each physical adjustment affects the actor’s interpretation accordingly. The Schimmel forced us to open up laterally and to physically broaden ourselves. The performances expanded into wider gestures and larger steps, and of course that affects breathing and voice production. The lines take on a different quality and we need some time to hear ourselves as we speak to find out if it’s working; as we listen, we learn from our instinctual selves some secrets about the character that have nothing to do with control. The subtleties that simply can’t be seen over there on the sides are instantly rejected by the next performance. The line that was so charmingly snappy seems too quick for a stage this wide, so you take a few extra steps before you start the line, and you find that the pause is very good for the line— or it’s very bad for the line, so you rethink the line for the next show.

Our preparation was such that the show started previews at the Schimmel Center on March 1, two days earlier than scheduled— still, though, it was hard. The particular demands of that space forced us to shift our focus from ourselves to the tasks at hand: namely, how do we slightly change the blocking so as to be seen by all the people way the hell over there on the sides, yet stay in the light and act our pants off at the same time? How do I play a favorite intimate speech to the front row when it’s twenty feet away? And how do we stay focused in spite of all this while the New York Times is deciding our fate?

How is what a company discovers, and it either happens or it doesn’t.

The first house was full of that kind of discovery, and we were learning a great deal in a very short time— with one of the hippest audiences in the world. The New York Jewish audience came to see why anyone would do this anti- Semitic play, and when they left they were glad they came because this Shylock was a man of great dignity, a man who was terribly wronged, a man who stood up to the system and demanded his hour in court. The play had its most critical audience in New York, where there are more Jews than in Tel Aviv; the laughs and the groans were aimed at the stuff that we knew was sensitive, but we were not prepared for the vocal response, which indicated to us that they were pulling for us, agreeing with us, letting us know that we were on the right track— and sometimes the wrong track.

The Schimmel Center happened to be our first hurdle and it served to gather us, to shape us. The box office treasurers welcomed us into their community with homemade cookies from time to time. Cold New Yorkers? I don’t think so. I should add that some of the company liked the Schimmel best; it was very good to us. To top it off, we got some of the finest reviews for American Shakespeare ever.

The show moved to Chicago and opened in the Bank of America (Majestic) Theatre on March 17. It was the biggest house we played, and the sight of those 2,200 seats and three balconies took my breath away. It was like looking at the bleachers from home plate. It’s daunting, because after successfully adjusting to the Schimmel with a back row several feet above your eye line, you now had to tilt your head considerably: first of all so they could hear you, but also, and equally importantly, so they could see your eyes. In warm- ups before each performance we were continually reminded to keep our chins up, which is a dandy note when you’re trying to do Shakespeare as naturally as breathing.

There were a few other elements of the Chicago stint that contributed to the success of that run. First of all, it had horsehair- plaster walls, which are excellent for acoustics; and second, it had one of the best crews I’ve ever worked with. The crews in all the theaters were fine, but Chicago is a union town and so everything was smooth as silk, from the treasurers to the house staff to the running crew. It was a terrific organization and contributed much to our performance.

The Chicagoans in the audience changed the flavor of the show as well. I’m from the Mexican border; most of my schoolmates were Chicanos, and Spanish is my second language. I spent a great deal of time in Juárez with the families of friends who lived there, and I believe that I have a Mexican soul, so the presence of a large Chicano population in Chicago reminded me of their second- class status in the 1950s. It was rotten, and there are still echoes of it now. So when I played Shylock in that big theater, I was playing that time of my life when the cops kicked us around and made jokes about our accents. Chicago also injected an American energy into the show, a bustling, big energy that shored up our American interpretation. It was the time of the Japanese tsunami, and after each performance we made an appeal for donations to the American Red Cross Japanese Relief Fund. I thought about how we were helping those people who not many years ago we had thrown out of their houses and interned, imprisoned, and ghettoed.

Chicago was great because we learned not only that we could play a house that size, but that we could play it well. By the end of two weeks there, we were really cooking.

We opened on March 29 in Boston’s Cutler Majestic, a gorgeous, beautifully renovated Beaux Arts theater at Emerson College. When it opened in 1903, it was dubbed “The Gold Room”: gilt decorations are everywhere, from the huge roses on the gently curving proscenium to the angels with outspread wings that hold up the balconies. It is glorious to play this house. And voluptuous. The dominant color is a dark rose- pink, and from the actor’s point of view it feels like you’re standing in an open mouth, the back of the throat being the stage, with the roof of the mouth mounting in ornate, flower- decked trellises to enclose two cantilevered balconies. There are no chandeliers or support columns, so the sound is unobstructed. Horsehair-plaster walls help make it a 1,200- seat acoustic gem.

This was the third of the four theaters on our tour, and I feel it’s the one where our Merchant of Venice came into its own; we gave a solid, assured, freewheeling performance every time. No one said a thing about this sudden state of grace for fear of jinxing it, I guess, but by Saturday’s matinee we were grinning at each other.

Boston had a vigorous college atmosphere, full of eager anticipation and excitement. The house was so welcoming that the performances seemed to soar. I don’t know how the history of that town affected the performances. I’d like to be romantic and suggest that we were touched by the proximity to its early American inhabitants, but mostly I remember feeling completely at home in that great theater. The show fit there perfectly, and the town made us feel like it had taken us in. I don’t know how else to describe it except to say that some of the actors came into themselves in that place— partly because we had begun replacement rehearsals and were forced to reexamine the work rather than rest on our substantial laurels.

We closed in Boston in the rain, which pretty much describes the weather we had had for those first four weeks on the road, and then when we got to Santa Monica we moved into our sunny digs on the beach. Really, on the beach, and let me tell you what it’s like to play The Merchant in the bright sunlight. It’s tough. Because you just don’t want to work. It takes a different sort of concentration, a disconnection from that mesmerizing beach and the lazy bodies lying on it. So Santa Monica was the perfect place to close the play; it was a little present after all the rain.

But also, because we had to replace the actors in two major roles, it was like starting all over again, exploring our new relationships in this theater. The show didn’t suffer for that, but we simply couldn’t accomplish in two weeks with the new ensemble what had taken us two months to build.

We spent those last two weeks of our tour, from April 13 through April 24, in the Broad, the most actor- friendly theater I’ve ever seen. At 499 seats, it’s an intimate space, inviting and warm, with great acoustics. And they do something there I’d never seen before: they provide food and snacks for every performance. That’s unheard of— at least I’d never heard of it. What a terrific idea, and I imagine it has something to do with the fact that the director, Dale Franzen, was an opera singer, and that Dustin Hoffman had so much to do with the theater being built. No matter the reason, it was a real treat. It’s surprising how the little backstage details affect the energy of a production.

As for performing there, it was a relief not to have to push to be heard. After playing to some big houses it felt like we were on holiday, but no one got lazy— as always, we warmed up on the stage before each performance, and no one slacked off.

My “ring” speech was fairly consistent throughout the tour, and the audiences seemed to be touched by it in each of the theaters, but as the Broad in Santa Monica was the most intimate theater, it was the one in which the speech affected the audience most deeply. It was possibly that effective in the other theaters, but at the Broad I could see the audience much more clearly than in any of the others, and their response hit me every time. I felt as though they were going through that pain with me.

The difference in the performances at the Broad was our focus— we were concerned with moving on and with saying good- bye to this experience, which we were all aware was uncommon. I found myself curiously emotional the last week; tears would fill my eyes at the damnedest times. Naturally it affected the work, though by now we were so solid that, whatever our wanderings, the performance of the play was completely satisfying— and that is what bound us together so tightly. We knew what we had and we were justly proud, but we were never arrogant. There was a genuine humility about this company, a gratitude to have been part of such a good show. Our company pulled so closely together partly because of the vast differences between one house and the next. Doing the show on the road proved that our work was not limited to a so- called New York audience; it reached people all across the country just as deeply each time. I wish the custom of touring the original Broadway cast would return: the country deserves to see the people who create the events.

The experience of each performance— whether it be The Merchant of Venice or any other play— cannot be dissociatedfrom the theater it’s played in. And I believe that the memoryof each play remains in that theater, making up its soul. Everyhouse has certain demands, and when you serve them the housewill open to you. And of course if you are playing Shakespearethen there is always Will himself, ready to lend a hand wheneveryou let him.

Adapted From the Book: LIVING WITH SHAKESPEARE: Essays by Writers, Actors, and Directors

Edited by Susannah Carson

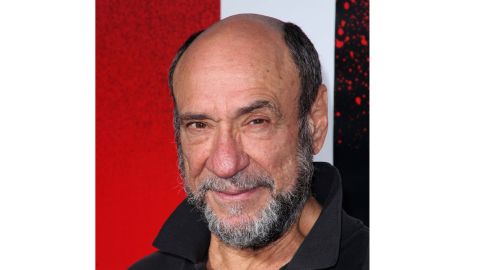

“Searching for Shylock” copyright © 2013 by F. Murray Abraham

Introduction and compilation copyright © 2013 by Susannah Carson

Foreword copyright © 2013 by Harold Bloom

Reprinted with the permission of Vintage Books, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc.

Image courtesy of Shutterstock.