Repost: Another World Creeps In

[Author’s Note: I’m reposting some old favorites while I’m away on vacation this week. This post was originally from April 2011.]

I’m an atheist, in part, because I’m a moral person.

When I first read the books that are called holy, what I found were countless passages that are abhorrent to the conscience: God drowning the planet in a global flood, massacring the innocent firstborn of Egypt, ordering Abraham to murder his son as a test of faith (and rewarding him for being willing to do it!), commanding the Israelites to wage genocidal war on other tribes, promising to torture nonbelievers in a burning hell forever, ordering the subjugation of women and the killing of gays, and so on and so forth. I find myself unable to give my allegiance to any text that praises such atrocities as virtues, much less to believe that these books were written by a perfectly good and benevolent being.

Liberal and moderate believers tend to deal with this by mythologizing these stories beyond all recognition, but I find this approach to be fundamentally dishonest. However many layers of allegory you bury these tales under, their brutal, violent message still bleeds through. What’s worse is that millions of theists go to church every week and read from scripture that still includes these stories unaltered. Why not release a new version of the Bible, one edited to reflect our evolving moral understanding, that omits them altogether?

But whatever the flaws of this approach, at least it tacitly concedes that these stories are immoral, their messages unacceptable. Other believers, some of whom I’ve been talking to in the last few days, take a different approach. They say that there’s another life, by comparison with which everything in this life is inconsequential, and any action God takes – up to and including the violent killing of children – is justified if it ushers souls to a better destiny in this other existence. Here’s one shining example from a recent post of mine:

…according to Christianity, death isn’t the end of the story. What if, instead of “God ordered the Hebrews to kill the Canaanites”, we read it as “God ordered the Hebrews to teleport the Canaanites from the desert to a land of eternal happiness where everyone gets a pony”? Does that change the verdict? Granted, the particular mechanism of teleportation in this case is downright unpleasant, but compared to eternity, it amounts to stubbing your toe while you step onto the transport pad.

The problem with this apologetic is that it has no limits. It can’t be contained to the handful of troubling cases where the apologists want to use it; like a river in flood, it inevitably bursts its banks and starts to rise and sweep away all firmly rooted moral conclusions. After all, what act could not be justified by saying that it creates a greater, invisible good in a world hidden from us? What evil deed could this not excuse? The same reasoning that’s used to defend violence, killing and holy war in religious scripture can just as easily be used to defend violence, killing and holy war in the real world.

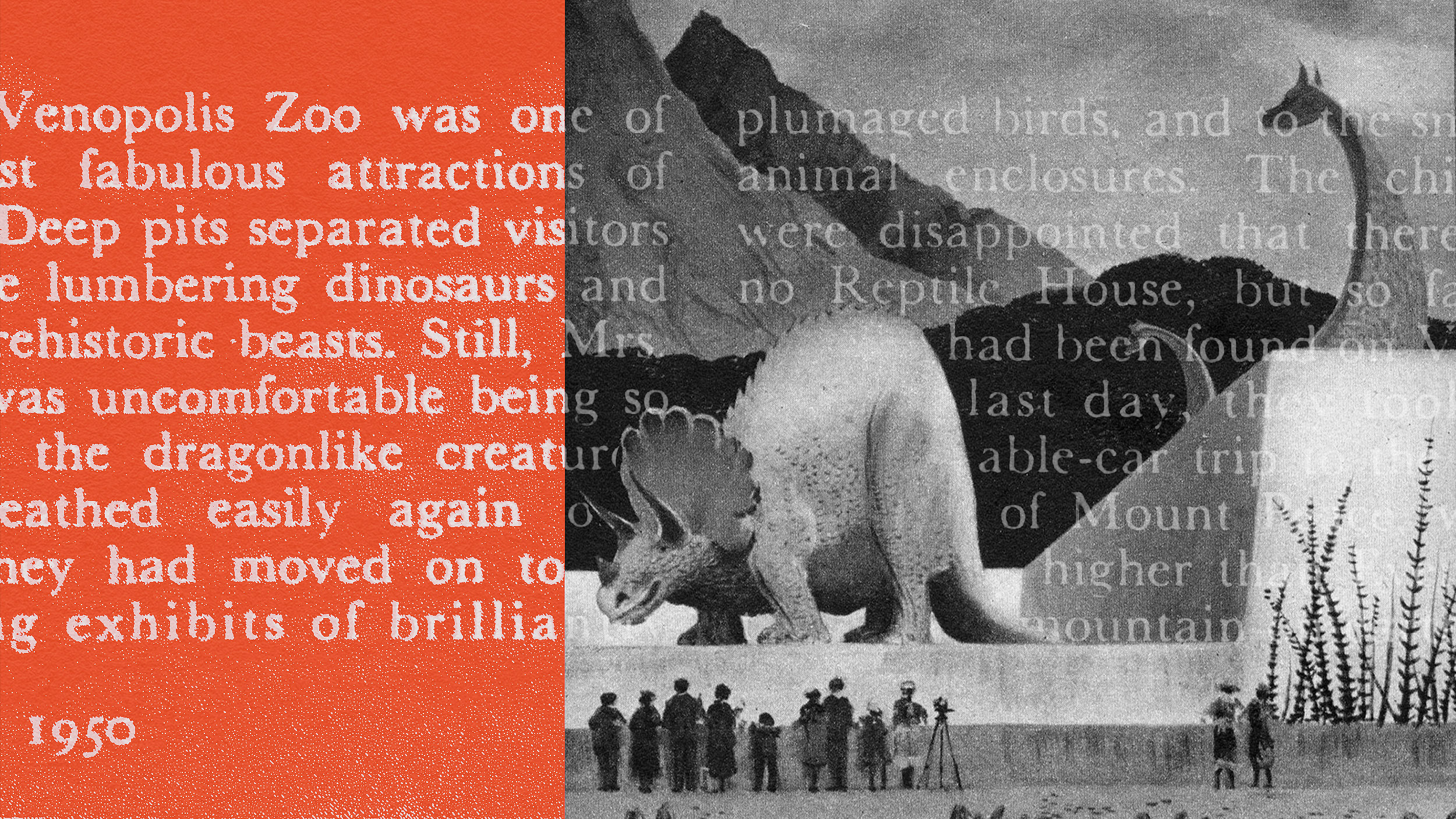

To a humanist who takes this world as the standard of value, morality generally isn’t difficult or complicated. There are wrenching cases where real and significant interests collide and force us to make painful choices, but for the vast majority of everyday interactions, it’s perfectly obvious what the moral course is. In the light of rational humanism, we can see morality bright and clear, like looking out at a beautiful garden through a glass patio door.

But when you introduce another world, one whose existence must be taken entirely on faith but which is held to far surpass our world in importance, your moral system becomes weirdly distorted. That other world seeps in like smoke, like fog beading on the windowpane, obscuring our view of the garden outside and replacing clear shape and form with strange and twisted mirages. Like a universal acid, it dissolves all notions of right and wrong, and what we’re left with is a kind of nihilism, a moral void where any action can be justified as easily as any other.

This is what Sam Harris means when he says moderates give cover to violent fundamentalism; this is what Christopher Hitchens means when he says religion poisons everything. At one moment, these religious apologists seem like perfectly normal, civic-minded, compassionate people. But ask the right question and they instantly turn into glassy-eyed psychopaths, people who say without a flicker of conscience that yes, sometimes God does command his followers to violently massacre families and exterminate entire cultures, and the only reason they’re not doing this themselves is because God hasn’t yet commanded them to.

These beliefs have wreaked untold havoc on the world. This is the logic of crusade and jihad, of death camps and gas chambers, of suicide bombers detonating themselves on buses, of inquisitors stretching bodies on the rack, of screaming mobs stoning women to death in the town square, of hijacked airplanes crashing into buildings, of cheering crowds turning out to see heretics being burned at the stake. They all rely on the same justifications: God is perfectly in the right working his will through intermediaries; God is not subject to our moral judgments and his ways aren’t to be questioned; God is the creator of life and he can take it away whenever he chooses; and if any of these people were innocent, God will make it up to them anyway. These are the beliefs which ensured that most of human history was a bloodstained chronicle of savagery and darkness.

Only lately, and only through heroic effort, have we begun to rise above this. Only in a few rare instances have people come to the realization that this life matters most. And still we humanists, who see morality as a tangible matter of human flourishing and happiness, must contend with the fanatics who shrug at evil, or actively perpetuate it, in the name of the divine voices they imagine that they’re obeying. They rampage through the world, killing and burning and insisting all the while that they’re doing God’s will. And the crowning absurdity of it all is that they insist not just that their beliefs make them moral, but that they’re the only ones who are moral, and that we, the ones who value and cherish this world, are the nihilists!

Here’s another apologist from the same thread I quoted earlier, the one comparing ancient Hebrews impaling Canaanite babies on spears and chopping them up with axes to the slight pain of a stubbed toe:

What is at issue is that atheism per atheism does not really allow for things such as morals at all…

What in the world is so bigoted about stating the incongruity between atheism and morality?

The black-is-white, up-is-down audacity of this claim shows how severely religion can warp a believer’s moral compass, to the point where they’re willing to defend genocide as good and condemn those who don’t share that opinion as evil. I say again: I’m an atheist, in part, because I’m a moral person, and because I value human beings and the world we live in more highly than the dictates of ancient, bloody fairytales. Come what may, I see the garden of human value in the light of reality, and no apologist for genocide and destruction will ever convince me that I should instead look for guidance in the fog.