Oldest Known Early Human DNA Recovered

This post originally appeared on the Newton blog on RealClearScience. You can read the original here.

As far as mountains go, the Atapuerca Mountains in Spain aren’t much to look at. In many places, they amount simply to scrub-covered, limestone hills rather than towering, craggy heights. If the mighty Rockies of North America could speak, they might very well be scoffing.

But at Atapuerca, the focus is more on the sediments below the ground than the rocks above it. The area is home to a treasure trove of buried archaeological riches: fossils and tools belonging to the earliest known species of ancient humans. Rightfully so, the United Nations and the World Heritage Organization have designated the archaeological sites at Atapuerca as protected World Heritage Sites, for providing “an invaluable reserve of information about the physical nature and the way of life of the earliest human communities in Europe.”

The most famous site at Atapuerca, Sima de los Huesos — “The Pit of Bones” — is precisely that. Located at the bottom of a 43-foot chimney in the winding cave system of Cueva Mayor, it contains approximately 5,500 ancient human bones dated at over 350,000 years old! Now, drawing upon this piled wealth of history, Matthias Meyer, a lead researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, and a team of colleagues have recovered and analyzed the earliest known human DNA.

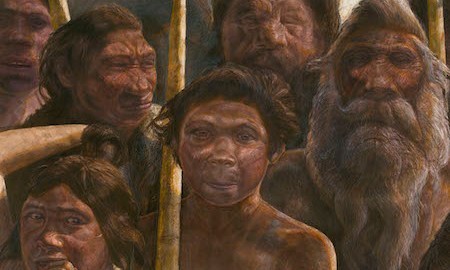

DNA, as you may very well know, is the molecular instruction manual for how to build life, and the DNA at Sima de los Huesos is thought to belong to Homo heidelbergensis, a group of extinct humans roughly comparable in height and looks to Neanderthals. Drilling into a femur present at the site, the team collected about two grams worth of bone, then isolated DNA using arecently discovered method that employs silica to make the process more efficient. The team focused on the DNA contained within mitochondria — the powerhouses of cells — which holds vastly fewer genes than does nuclear DNA, which is contained within cells’ nuclei. Because mitochondrial DNA is passed down exclusively from mothers, there are usually no changes from parent to offspring. This makes it a powerful tool for tracking ancestry, which is precisely what the researchers used it for.

After sequencing 98% of the mitochondrial DNA genome, Meyer and his colleagues estimated the specimen’s age using the length of the DNA branch as a proxy. The femur clocked in at around 400,000 years old, placing its former owner in the Middle Pleistocene and making the DNA by far and away oldest human DNA ever collected. The previous record belonged to 100,000-year-old Neanderthal DNA.

The team then attempted to determine the specimen’s position in the ancient human family tree and were surprised to find that the owner did not share a common ancestor with Neanderthals, but instead with Denisovans, a mysterious subspecies of human discovered in 2008 that last shared an ancestor with Neanderthals and Homo sapiens about one million years ago. Indeed, the more scientists discover about our prehistoric ancestors, the further they seem to fall down Alice’s Rabbit Hole. Things just get curiouser and curiouser.

Next up, Meyer plans to assemble nuclear DNA sequences from the specimens at the Pit of Bones in the hopes of learning even more about where they fit within the annals of human evolution. This will be a tall task, however. With a half-life of 521 years, DNA breaks down fairly rapidly even under the most optimal conditions: encased in glaciers or buried beneath arctic tundra, for example. Furthermore, with about 21,000 genes, human nuclear DNA presents a much more complex tome to completely piece together.

Source: Matthias Meyer et. al. “A mitochondrial genome sequence of a hominin from Sima de los Huesos.” Nature. December 2013. doi:10.1038/nature12788

(Image: Javier Trueba, MADRID SCIENTIFIC FILMS)