In Praise of the Small Art Museum

Waiting in line to pay admission late last month at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in a sea of heavy-winter-coated humanity, I asked myself why this has become the standard art museum experience—big building, big collection, big name exhibits, big crowds, and big admission prices. I began to think about all the smaller, quieter, more intimate museum experiences I’ve had. And then I came across Susan Jaques’ A Love for the Beautiful: Discovering America’s Hidden Art Museums, an extended love letter to as well as coast-to-coast tour of the forgotten art museums across America doing important work away from the maddening crowd. Following Jaques’ lead, here’s my own paean in praise of the small art museum.

For Jaques, it all started in St. Petersburg—Florida, not Russia. Touring the recently opened Salvador Dali Museum in that sunny state, Jaques and her daughter quickly realized that they had stumbled across the largest collection of Dali’s work outside of Spain. “Intrigued, I began searching for other unsung museums with extraordinary art collections,” Jaques explains. “After months of research and travel, I made a startling discovery. Some of the country’s best art resides in museums largely unknown outside their regions.” In many cases, those museums are even unknown within their regions, hidden either in the shadows of larger institutions or simply neglected as part of the everyday landscape.

Jaques, a gallery docent at the J. Paul Getty Museum, then takes you on a whirlwind tour of these hidden treasure troves. She does her level best to organize the mammoth list into categories, such as “Ancient Art,” “Asian Art,” and “Single-Artists,” but this really is a book you can dip in and out of at will. Jaques not only sets the scene for each institution, but also delves into the human element behind the collections, quite often the collectors and/or curators whose vision made dreams of a gallery into reality. Those stories are as much a highlight of each institution as the helpful “Not to Miss” feature that Jaques the incurable docent helpfully provides.

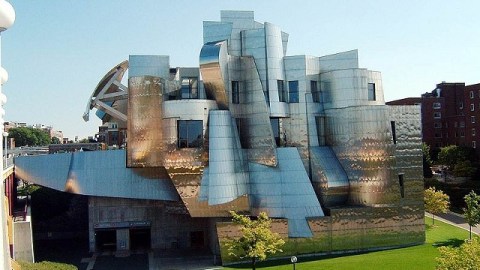

Jaques manages to surprise with nearly every museum chosen. A world class collection of African and Oceanic Art resides in the heart of Hoosier country (the Indiana University Art Museum). American Impressionists such as Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, and Theodore Robinson abound in “America’s Giverny” in Old Lyme, Connecticut’s Florence Griswold Museum. San Antonio’s McNay Art Museum creates a “Paris in South Texas,” just as Dallas’ Meadows Museum puts a “Prado on the Prarie.” Visitors to Tacoma, Washington’s Museum of Glass can watch glassblowers ply their trade in the museum’s “Hot Shop.” Travelers to the Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum on campus of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis (shown above) find themselves face-to-face with a miniature Guggenheim Bilbao by the very same architect Frank Gehry.

It’s an amazing list done amazingly well, but even then I kept creating my own list of hidden museums left out. When Jaques praises the Rodin collection of The Cantor Arts Center in Palo Alto, California (her territory), I wanted to counter with the Rodin collection of Philadelphia’s own Rodin Museum (my territory). But I think that’s the point of Jaques’ book—to uncover, to argue, and, in the end, to celebrate.

So, in the name of praising the small art museum doing big things, I give you Philadelphia’s La Salle University Art Museum. (Full disclosure: I teach at La Salle University, but have no connection to the museum.) First opening in 1975, the La Salle University Art Museum relies on donations and judicious use of a small budget to create a small but significant collection to serve the educational mission of the university. For many years, the guiding hand and eye of Brother Daniel Burke formed the museum into what it is today. Burke’s keen eye for great art made by lesser known names allows the museum to talk about Caravaggio, for example, not with one of the master’s priceless works, but with a fine example by the CaravaggistiBartolomeo Manfredi. (Burke also knew all the tricks of the trade, such as braving winter blizzards to attend New York City auctions when the more fearful competition stayed home.)

La Salle’s art museum’s collection represents all the home team, from the earliest Philadelphia-based or -connected artists such as Charles Willson Peale (and his brother James and son Rembrandt) and Christian Schussele to later 19th century artists Thomas Eakins, Henry Ossawa Tanner, William Glackens, and William Sartain to modern artists Sidney Goodman and Bo Bartlett. The collection’s surprisingly strong in terms of the early 19th century British school of portraiture, with fine examples from Thomas Lawrence, Henry Raeburn, Richard Cosway, and John Opie. A wonderful portrait by Carolus-Duran could be mistaken for a later work by his prize student, John Singer Sargent. And, although a Tintoretto in the corner claims pride of place in one gallery, I kept coming back to Joos van Cleve’s Leonardo-esque Madonna of the Cherries, dominated by a rich, cherry red that would make even da Vinci blush. Such wonderful discoveries in such a hidden museum are what will keep you coming back, all with the usual added appeal of small crowds or even a gallery all to yourself.

Beyond the collection regularly on view, the La Salle museum offers small, but targeted exhibitions that fill in the cracks that the blockbusters leave behind. Their current special exhibition Strategic Ambiguity: The Obscure, Nebulous, and Vague in Symbolist Printstakes the big museum subject of Symbolism and focuses just on the prints those artists made. The standard Symbolists such as Odilon Redon and Gustave Moreau (via an etching of his L’Apparition) appear, but by connecting the Symbolists to the Nabis through printmaking, the exhibition adds a whole new dimension to artists such as Maurice Denis, Pierre Bonnard, Edouard Vuillard, and Paul Gauguin. The curator even manages to sneak female Symbolist Jeanne Jacquemin and her androgynous (possible self-) portrait titled Saint George into this boys club. The curator strategically placed Saint George beneath a wall card discussing early Symbolist exhibitions, which one organizer excluded women from based on “magical laws.” Educational (and entertaining) touches such as those might not be found or even exist in larger institutions.

Regardless of whether you’re a college student, an ardent gallery-goer, or just curious, follow Susan Jaques’ example and either read A Love for the Beautiful: Discovering America’s Hidden Art Museums to discover what’s out there, or just look around where you are now and see the art that’s quietly been waiting for you all along.

[Image:Frank Gehry‘s exterior design for Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum on campus of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Image source.]